Also by Richard Rhodes

Energy

Hell and Good Company

Hedys Folly

The Twilight of the Bombs

Arsenals of Folly

John James Audubon

Masters of Death

Why They Kill

Visions of Technology

Deadly Feasts

Trying to Get Some Dignity

(with Ginger Rhodes)

Dark Sun

How to Write

Nuclear Renewal

Making Love

A Hole in the World

The Making of the Atomic Bomb

Looking for America

Sons of Earth

The Last Safari

Holy Secrets

The Ungodly

The Inland Ground

Copyright 2021 by Richard Rhodes

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Harvard University Press for permission to reprint previously published material from the following:

The Insect Societies by Edward O. Wilson, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright 1971 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Sociobiology: The New Synthesis by Edward O. Wilson, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright 1975 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

On Human Nature by Edward O. Wilson, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright 1978 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

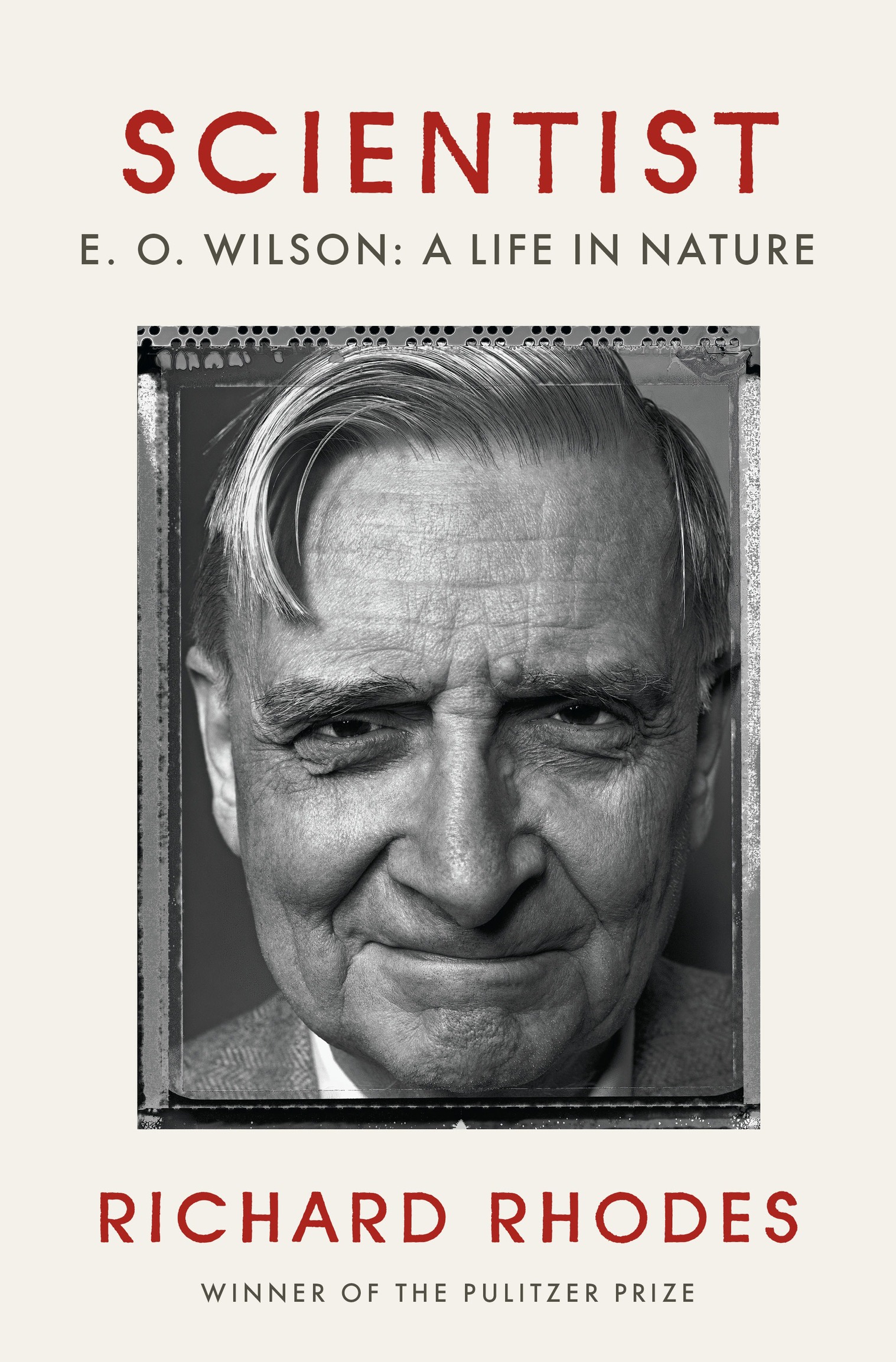

Cover photograph by Jenny Leutwyler / Contour / Getty Images

Cover design by John A. Fontana

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021944184

Hardcover ISBN9780385545556

Ebook ISBN9780385545563

ep_prh_5.8.0_139322223_c0_r1

For Ginger

A grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation

supported the research and writing of this book.

Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.

Theodosius Dobzhansky

Contents

Specimen Days

Museum of Comparative Zoology

at Harvard College

Cambridge 38, Massachusetts

Directors Room

November 2, 1954

To whom it may concern:

This will introduce Mr. Edward O. Wilson, a junior fellow in Harvard University. Mr. Wilson is traveling to Australia, Ceylon, New Guinea and New Caledonia for the purpose of collecting scientific specimens for the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Any assistance or advice you may be able to give him will be greatly appreciated.

Very truly yours,

Alfred S. Romer

Director

F inally, Ed Wilson was on his way, twenty-five years old, tall and lanky, the upper range of his hearing gone since his teens, his right eye ruined in a childhood accident: half deaf and half blind. Outwardly, he was a polite, soft-spoken product of Gulf Coast Alabama, the first in his family to graduate from college. But behind the well-mannered finish he was as tough as nails, as bright as the evening star, and no mans fool. He would become one of the half-dozen greatest biologists of the twentieth century. In the new century now advancing, he would lead the charge to save whats left of wildernesshalf the Earth, he saidnot only for the experience of wilderness but also for the millions of species large and small, many of them not yet even named, in danger of going extinct, forever. If they did, he taught, they would take with them their supporting strands of the great web of life, unraveling the world. Trees can be replaced; species, having evolved into being across millions of years, are irreplaceable.

For now, a fresh-minted Ph.D., just setting out, his lifework before him, young Wilson was bound for the South Pacific to collect ants. Entomology was his fieldinsect biologyand ants were his specialty. No one had ever systematically collected ants across the vast sweep of the South Pacific. For ant specimens, many Pacific islands had never been explored.

The new frontier in 1954, after James Watson and Francis Cricks great 1953 discovery, was the structure and function of DNA. Biologists everywhere had run to their labs to inform their science with chemistry and physics. Wilson was deliberately running the other way. If a subject is already receiving a great deal of attention, he explained his strategy later, if it has a glamorous aura, if its practitioners are prizewinners who receive large grants, stay away from that subject.

Wilson was an explorer at heart, had been since he was a small boy. Rather than focus his work on one species, as most of his peers would do, he preferred to break new ground, find the big nuggets, assay them, and move on. If hed started his life as an only child in the Gulf Coast South, chasing down snakes and butterflies, hed arrived at Harvard for graduate study in 1951 as a certified prodigy. In a vacant lot in Mobile, Alabama, when he was only thirteen years old, hed been the first collector in the United States to spot the invasion of the pestilential red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, transported from Argentina as a ship stowaway. Seven years later, as an undergraduate at the University of Alabama, hed published his first scientific paper.

Avoiding the crowd was a risky strategyone that would reward him repeatedly across a long, successful career, but would also vex him with major challenges. Take a subject instead that interests you and looks promising, his advice continues, and where established experts are not yet conspicuously competing with one another. You may feel lonely and insecure in your first endeavors, but, all other things being equal, your best chance to make your mark and to experience the thrill of discovery will be there. The advice was vintage Wilson, potentially beneficial in equal measure to the curious boy and the ambitious adult.

A Harvard Junior Fellowship stood behind his one-man expedition to the South Pacific on behalf of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. The exclusive Society of Fellows, founded at Harvard in 1933, annually awarded a dozen exceptional young scholars three years of support for any research or study they chose to undertake. Across the decades, the ranks of Harvard Senior and Junior Fellows have included such well-known leaders as the presidential adviser McGeorge Bundy, the historian Crane Brinton, the Nobel-laureate physicist and Manhattan Project veteran Norman Ramsey, the strategic analyst Daniel Ellsberg, the economist Carl Kaysen, the transistor co-inventor John Bardeen, the artificial-intelligence pioneer Marvin Minsky, the geographer and historian Jared Diamond, the behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner, and the U.S. poet laureate Donald Hall. In 1954, the Society added Ed Wilsons name to its list.

Collegial dinners every Monday night in term time introduced Wilson to such visiting stars as the charismatic J. Robert Oppenheimer, a high-school hero of Wilsons at the end of World War II, when Oppenheimer emerged as the so-called father of the atomic bomb. Promethean intellect triumphant, Wilson would recall his assessment of the famous physicist, master of arcane knowledge that had tamed for human use the most powerful force in nature. Junior Fellows were expected to attend such weekly dinners as well as twice-a-week luncheons with their peers. Wilson would miss a share of both in his nine-month Pacific expedition.