To

Walton Shreeve

and

Phyllis Heidenreich Shreeve

(19222000)

Dass ich erkenne, was die Welt

Im Innersten zusammenhlt

Ill learn what holds the world together

There, at its inmost core.

GOETHE, Faust

PROLOGUE

On the morning of June 26, 2000, a short, elderly man walked up the pedestrian lane along the east side of the White House grounds and joined a couple of dozen people already gathered outside the guest entrance, under the shade of the willow oak trees that line the lane. It was the beginning of a sultry Washington day, one of the rare ones in that mild summer, and the mans shirt was already damp from perspiration. That I should live to see this day is beyond belief, he said, to no one in particular. I was there in the beginning, you know. I was there before DNA.

Norton Zinder, professor emeritus at Rockefeller University, had been a molecular biologist since before 1953, when James Watson and Francis Crick made the essential discovery that the shape of the deoxyribonucleic acid molecule, or DNA, enabled life to happen. He had made some important contributions back then, too, and much later, in the late 1980s, he had helped Watson organize a government science program called the Human Genome Project. Its goal was to reveal the innermost secret of life: the entire code, spelled out in the language of DNA, for the construction and maintenance of a human being. Like the others waiting in the shade, he had been invited to attend the presidents announcement that the human genome had at last been deciphered.

Zinders gratitude for having lived until this June day was not entirely rhetorical. He had recently suffered a stroke. While he was recovering, he had tried to mediate a globally watched conflict that had very nearly turned the Human Genome Project into the uttermost embarrassment in science and was well beyond his ability to resolve. But the attempt had wrenched sleep from him, and for several weeks he had felt as if he were living on Valium. He was afraid another stroke would kill him before he could see the end of what he had helped begin.

Zinder talked for a whilehe was a voluble man, and the stroke had perhaps made him a little more soabout the significance of this day, and recounted his memories of his life in science, which fell out of him in a semi-organized rush, like folders spilling out of a file cabinet. Meanwhile, other guests continued to arrive. Most were scientists. They were all dressed up for the occasion, and from their solemn excitement when they greeted each other, one sensed that they were not accustomed to seeing their colleagues decked out in such finery. At about 9:30, James Watson himself appeared. A line to go through security had formed along the fence, and he was standing in it by himself: a tall, hollowchested figure in a white suit and a floppy tennis hat. He was staring into the leaves of the willow oaks, his mouth hanging open slightly. Someone asked him how he felt on such a momentous occasion. Its a happy day, he answered. But he did not look happy. He looked like a man going through the motions of being happy.

In line behind Watson was a much shorter man, dressed in an expensive dark suit and a light blue shirt with a white collar. It was the kind of business-class shirt that a scientist would never wear, even to an event at the White House. His name was Tony White. He was the CEO of PE Corporation, and he had just flown in on his private jet. He did not look any happier than Watson. Other than that, there couldnt be more contrast between the two men. Watsons face was long, bleached, and spotted, and he seemed to be composed mostly of limbs. White was round and compact, like a cannonball. His face was red, his collar was tight, and he was peering around nervously, as if hed been invited to a party hosted by an enemy. Somebody asked him too how he felt on the occasion. I dont know how you go from blatantly trashing each other to being all lovey-dovey overnight, he said. Ive had nothing to do with this. He pulled out a cell phone. Where is everybody? he grumbled into it. Maybe there was some other way of getting down here that I wasnt informed about. He snapped the phone shut and shoved it back into his pocket.

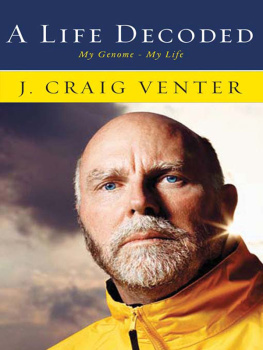

Watson and White had arrived at the White House from different worlds, and they remained oblivious to each other. They existed on either side of a wall that has traditionally divided science into two camps: the basic research conducted in university labs and nonprofit institutions like Watsons Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island; and the applied science of pharmaceutical companies, biotechs, and other corporations aimed at developing a marketable product, often using the results of academic research as a jumping-off point. There is of course some traffic back and forth, and people on both sides of the wall believe they are serving the public good. But the two camps obey different codes of conduct and reward excellence in different ways. The currency of academic excellence is recognitionpublications, honors, and the esteem of colleagues, with the highest accolade being the Nobel Prize. The currency of success in commercial science is currencylots of it, in some cases. Watson and White epitomized these separate worlds. The only reason the two men were in line together on that June morning was that another scientist, who was at that moment inside with the president, had tried to excel on both sides of the wall simultaneously, which violated everybodys rules. His name was J. Craig Venter. Whether or not he had succeeded was an open question. But he had certainly succeeded in pissing a lot of people off, Watson and White among them.

A science policy administrator, Kathy Hudson, arrived carrying a fresh copy of Time magazine. She passed it around and people leafed through it, laughing and admiring the pictures in the lead story. On the cover of the magazine, two scientists stood shoulder to shoulder, one a little behind the other. Both men were dressed in white lab coats. (Journalistic protocol demands that lab coats be worn by scientists during photo shoots; otherwise we might not be able to tell them from other people.) The scientist on the right was Francis Collins, chief of the governments Human Genome Project, who was also inside with the president. The photo showed a man in his late forties with a large square face, thick brown hair, a neat mustache, and a dogged set to his mouth. The scientist on the left was J. Craig Venter. He was bald, with upturned eyebrows and an oval face tapering down to a mouth that flickered up at the corners, as if he were trying to suppress a grin. His face was dramatically bifurcated by the photographers lighting, the right side aglare and the left in shadow.

Two years earlier, in May 1998, Venter had announced that with backing from PE Corporation (then known as Perkin Elmer), he was going to form a private company to unravel the human genetic code and would complete the project in three years instead of the seven more years estimated to be needed by the publicly financed Human Genome Project. By making the human code available to the world so soon, he hoped to greatly accelerate the pace of biomedical research and thereby save the lives of thousands of people who would otherwise die of cancer and other diseases. He also hoped to become famous, well loved, and very rich. It was a big gamble on all counts. Nothing like the particular scheme he was proposing had been attempted before. If it were broken down into its various technical components, most of them had never been attempted before, either. All of these untested elements would have to work seamlessly together or the whole enterprise would fail. If it did work, it would be a scientific achievement of huge importance. But even then, few people really understood how it would make Venters proposed company any money. Those who knew Venter were not surprised that he was going to try anyway. Craig likes to do high dives into empty pools, one colleague said of him. He tries to time it so the water is there by the time he hits the bottom.

Next page