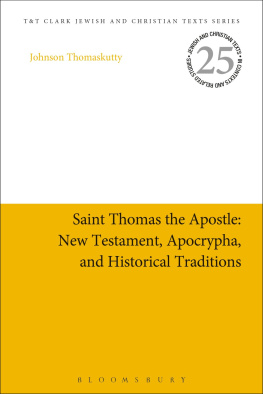

JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN TEXTS IN CONTEXTS AND RELATED STUDIES

Executive Editor

James H. Charlesworth

Editorial Board of Advisors

Motti Aviam, Michael Davis, Casey Elledge, Loren Johns,

Amy-Jill Levine, Lee McDonald, Lidia Novakovic, Gerbern Oegema,

Henry Rietz, Brent Strawn

Saint Thomas the Apostle

New Testament, Apocrypha, and Historical Traditions

Thomaskutty Johnson

Foreword by

James H. Charlesworth

Bloomsbury T&T Clark

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

According to Mackinders Heartland Theory of 1904, he who controls the Heartland of Europe controls the world island. This slogan helped to define the twentieth century. Primarily, Eurasia was in focus. What was important was the West; this theme even defined the expansion of America as in the well-known slogan Move West, young man, move West.

In terms of biblical research, I see this Eurocentric vision as beginning with a Christian devotion to Paul who led missionary journeys to the West and to the far West, or Spain, by his own expectations expressed in Romans 15:24. Too many introductions to Christian origins focus on Peter and Paul, both of whom were probably martyred in Rome. Thomas and movement eastward are often neglected in such publications. The devotion to Mary, Mary Magdalene, and other Apostles, including Philip, John, and Thomas are, in contrast, scarcely mentioned. The documents later canonized and especially the additional early Christian writings show Christian fascination and preoccupation with each of these women and men who were so close to Jesus of Nazareth. Such early Christian compositions are too quickly dismissed as documents of the Apocryphal New Testament. Texts such as the Gospel of Thomas and the Acts of Thomas are fundamental for understanding Christian origins. However, the word apocryphal does not mean unimportant. As such, the present book by Professor Thomaskutty, who teaches in India, brings back into focus not only the apocryphal compositions but one of the lost figures of Christian origins: Thomas, the Twin.

Christianity began in the East in ancient Palestine. Jesus originated from the easternmost portions of the Roman Empire. He was a devout Jew whose vision was the Holy Land, and, as a prophet, he called Israel to repent and to prepare for Gods rule. According to Mt. 6:10, Jesus taught his followers to pray for Gods will to be observed on earth. The prayer was originally spoken in Aramaic, and on earth would thus most likely mean in the Land promised to Abraham (Greek: , ). Recall also that according to Matthew, Jesus returns from Egypt into the land of Israel ( 2:20).

Scholars of Christian origins often recite how Tertullian (c. 160250), Cyprian (c. 200258), and Origen (c. 185c. 254) exhorted Christians to recite the Lords Prayer. Attention is thence drawn to the West; Tertullian represented North Africa (esp. Carthage) and Italy, Cyprian also represented Carthage, and Origen lived in Egypt and Caesarea Maritima, a city in Palestine defined by the West. But what about the East? What about the evidence of Nestorians in China before the sixth century CE and what about India? How did the Thomas traditions migrate to that large and complex continent?

According to Acts 2, the majority of those who heard the apostles, including Thomas, were from the East, as the following peoples were present: Parthians, Medes, Elamites, residents of Mesopotamia, Egyptians, and Arabians. This report also seems to indicate that there were many people from the East in Jerusalem before 70 CE.

Thomas has been maligned and branded as doubting Thomas. The source text for this misinterpretation is John 20; yet, in this chapter, Thomas asks a question, indicating that he is a good disciple, and supplies the criteria for resurrection belief. He never doubts Jesus; he asks to experience what the other disciples have experienced and supplies data seen only by the Beloved Disciple. Many experts perceive that John is the greatest drama in the New Testament; if so, we should recognize that dramatically, only Thomas and Jesus appear in the final scene. Throughout this masterpiece, the author of John seeks to demonstrate the proper confession; it is thus significant that he allows only Thomas to express the perfect confession and positions it at the end of the Gospel of John: my Lord and my God. The importance and position of this confession is lost to those who do not recognize that Chapter 21 was added as an appendix to bring the East and West closer together. In my The Beloved Disciple , I was surprised that I was unable to falsify the hypothesis that Thomas was the Beloved Disciple in John. Surely I in the West could not be oblivious to the claim that others in the East had imagined long ago that Thomas was certainly the Beloved Disciple.

From the second to the fourth centuries CE, many documents were composed under the name of Thomas and in honor of him. In this book, critical scholars opinions are judiciously analyzed by Thomaskutty. They include the erudite discussions of the following compositions:

The Gospel of Thomas

The Book of Thomas the Contender

The Acts of Thomas

The Infancy Gospel of Thomas

In my The New Testament Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha: A Guide to Publications , I drew attention to more compositions highlighting Thomas: The Minor Acts of Thomas , the Apocalypse of Thomas , and the Consummation of Thomas . But these compositions are not nearly as important for this exploration as those chosen by Thomaskutty.

In the West, Thomas is not considered an ideal disciple because of a misinterpretation of John 20 in which Thomas is maligned as a doubting Thomas. The interpretation misrepresents the Greek language, the narrative, and the rhetoric. In the West, especially in Rome, Peter is saluted as the head of the Church, and this thought is grounded in an exegesis of Matthew 16.

In the Gospel of John, we find innuendos that Thomasespecially if he is the Beloved Discipleis superior to Peter. From Jerusalem through Edessa, and certainly in India, Thomas was honored. He was the ideal follower of Jesus Christ. According to John, when Thomas first spoke and urged others, he may have been the leader among the Twelve. Thomas counsels that all disciples should follow Jesus until his death, words that foreshadow the setting at the cross. The male disciple, called the Beloved Disciple, is placed by the Fourth Evangelist at the foot of the cross. He sees the spear go into Jesuss side. Thomas refers to it as one of the criteria, something he would have known if he was the Beloved Disciple. Finally, Thomas alone is chosen to make the perspicacious and concluding confession: My Lord and my God.

Beginning in the fifteenth century CE, the Church in India was sometimes persecuted by European Christians, especially the Portuguese, who burned all the ancient Indian writings they could find. The Europeans may also have judged that Indian Christians did not approve of images, read scripture in Syriac not Latin, and did not subscribe to the Christology of the West.

It is imperative to rethink New Testament scholars and early church historians conclusion that there cannot be any history in the Acts of Thomas. Here are my seven reasons that indicate such a reopening of research is warranted: