Contents

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

1994 by Urs App

Originally published in 1994 by Kodansha America, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: Characters for Yunmen by Marlow Brooks

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING - IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Names: App, Urs, 1949 | Yunmen, 864949. Works. Selections. English.

Title: Zen master Yunmen: his life and essential sayings/Urs App.

Description: Boulder: Shambhala, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017017312 | ISBN 9781611805598 (pbk.: alk. paper)

eISBN9780834841130

Subjects: LCSH: Yunmen, 864949. | Zen BuddhismDoctrines.

Classification: LCC BQ 998. U 59 A67 2018 | DDC 294.3/927092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017017312

v5.3.1

a

To Richard DeMartino

Contents

List of Figures and Tables

Yunmen Monastery Gate and Mt. Yunmen

Monastery facade (1990)

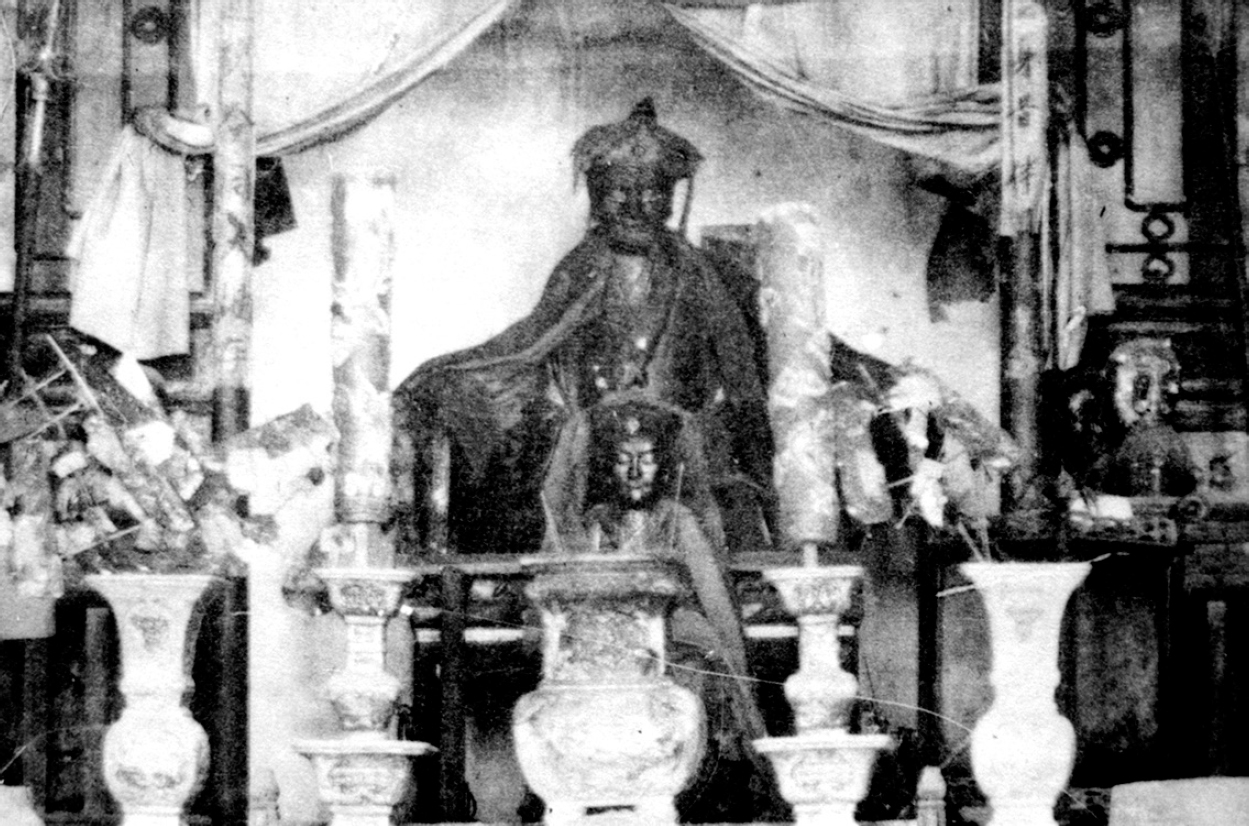

Mummy of Master Yunmen (1928)

Woodblock print of a preface to the Record

Overview of Chan in history

Yunmen as imagined by Hakuin

Replica of Master Yunmens mummy (1990)

Stream on Mt. Yunmen and poem

Table of important koans featuring Master Yunmen

Fig. 1: Outer gate of Yunmen monastery, Mt. Yunmen (U. App, 1990)

Preface

J OURNEY TO M T . Y UNMEN

In the summer of 1990 I made a pilgrimage to the monastery at the foot of Mt. Gate-of-the-Clouds (Mt. Yunmen) in southern China, the place where Zen Master Yunmen taught more than a thousand years ago. After a seven-hour train ride north from Chinas southernmost metropolis, Guangzhou (Canton), I arrived after midnight in the city of Shaoguanone hundred years ago an outpost feared by Wesleyan missionaries because of its hot and humid climate and rampant disease but today just another dusty provincial city. The next morning a bus took me about twenty-five miles westward to a town called Ruyuan (Source of Milk), a small settlement in the free zone of the Yao people, a dark-skinned ethnic minority whose striking blue-and-purple costumes appear exotic even to most Chinese. A deep blue river wound its way through this town, and above its tree-lined market streets rose mountains, majestic and green throughout the year. From the bus station I walked north on a sand-covered road glimmering in the midsummer heat. Making my way through a pretty valley dotted with rice fields and banana orchards, I encountered only a few people: a boy guiding a water buffalo, a peasant killing a snake at a roadside well, and a group of herdsmen taking a siesta on a meadow.

After I had walked for two hours, the valley expanded across a pass into a broad, spectacular plain flanked on the right by a series of mountainscascades of bold curves shimmering in ever more subtle shades of green and gray under the blinding midday sun. Due to the consistently warm climate, the entire plain was a single magnificent mosaic of rice terraces in all stages of cultivation. These squares of green, brown, and yellow were separated from one another by rows of banana trees waving their huge leaves lazily in the humid heat and by patches of swamp adorned with majestic lotus flowers.

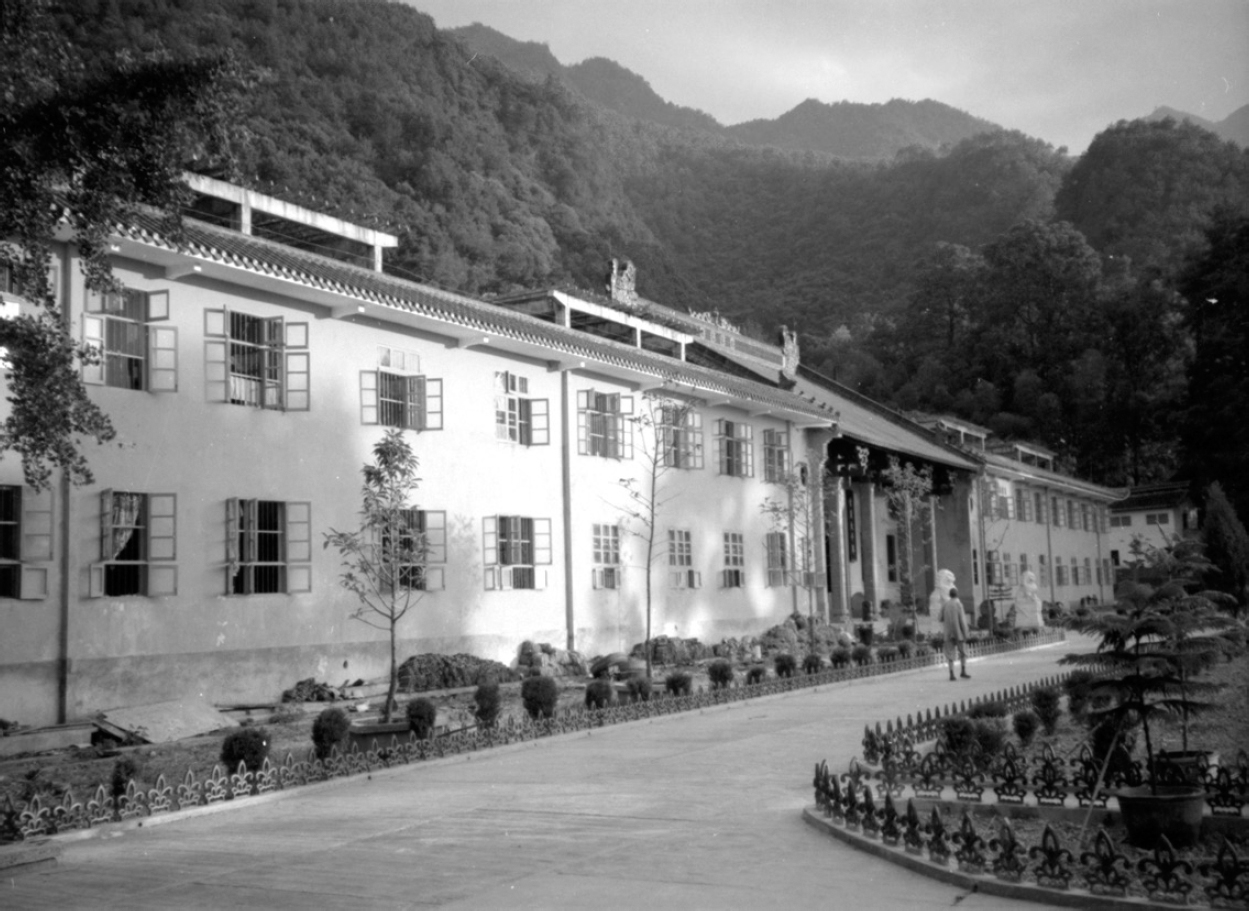

On the left this picturesque plain was overshadowed by a densely overgrown mountain shooting upward in spurts: Mt. Gate-of-the-Clouds or, in Chinese, Yunmen-shan. A little over one thousand years ago this mountain had housed the Chan master called Wenyan who became famous under its name: the master of Mt. Yunmen. Born in 864 near Shanghai, he had come to this region when he was just about sixty years old, and at the foot of the mountain had founded the monastery whose long yellow facade I saw glowing under thousands of green roof tiles.

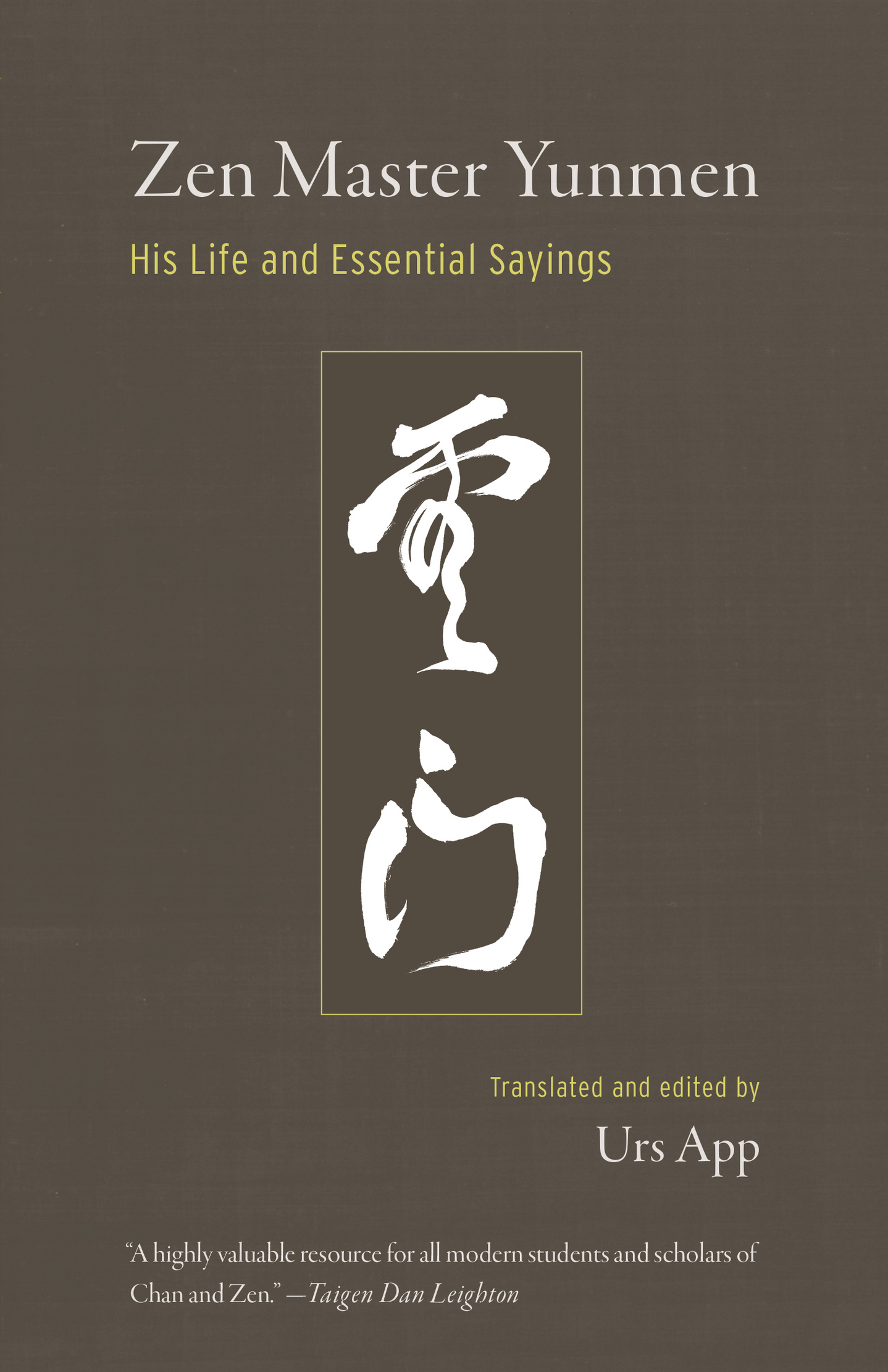

The monastery buildings of 1990 were mostly built during the preceding ten years. This large construction project was initiated by the abbot of the monastery and partly financed by the regional government, which is interested in the monastery not only as a cultural site but also as an attraction for Chinese and foreign tourists alike. After entering the walled-in monastery compound through an outer gate, visitors first find themselves in a courtyard with a curved pond. A long, two-story building, whose yellow facade I had glimpsed earlier, sits on one side of the courtyard.

Fig. 2: Main facade of Yunmens monastery (U. App, 1990)

An open gallery at its center leads through to the main monastery grounds. There one is faced with a maze of tree-lined courts and buildings of various sizes, dominated by the massive Buddha Hall where sutra chanting and religious ceremonies take place every morning and evening. Behind it is the Founders Hall that used to house the mummy of Master Yunmen ().

Fig. 3: Yunmens original mummy (1928)

This mummy disappeared during the Cultural Revolution, and a lacquered wooden replica now takes its place (). The meditation hall at the back of the monastery is comparatively small. It appears to be little used outside the two traditional three-month periods of intensive meditation that take place every year. The monastery also has spacious rooms for study, a small library, and a kitchen and dining hall of impressive size. In 1990 the monastery was home to about eighty monks living, unlike Japanese Zen monks who are housed in large halls, in small individual rooms. They follow a strict schedule of prayer, religious ceremony, and work. During my visit the monastery also housed scores of workers busy with construction. Forty nuns occupying the nearby brand-new nunnery helped to run the monastery and participated in the daily ritual.

The square monastery grounds are enveloped toward the mountainside by rows of trees planted by the last famous Chan master who resided here, Xuyun (Empty Cloud, 18581959); he is buried where the trees meet at the back of the monastery. From that point, a narrow and newly paved path leads into a steep gorge overgrown with luxurious green trees and plants that is filled with the perfumes of exotic flowers and the insistent droning of several kinds of cicadas. Playing hide-and-seek with a rushing brook, the path winds uphill until it ends at the foot of a waterfall, next to an oval pool overlooked by a small hexagonal pavilion. Those prepared to climb can reach two more waterfalls farther up the gorge (Fig. 8).

Although the monastery at Mt. Gate-of-the-Clouds is now waking up to renewed greatness, it suffered many centuries of neglect and decay. When the Japanese researcher of Buddhism Daij Tokiwa visited it in 1927, it consisted only of a few dilapidated buildings. In his report, the great scholar complained that the one remaining monk did not have the slightest idea of its great history and could not even name the master who had founded it. In addition to discovering the mummy of Master Yunmen (Fig. 7) and some door plates, Professor Tokiwa stumbled on further important remnants of the monasterys illustrious past: two stone slabs, or stelae, each the size of a man, standing abandoned in a corner. Engraved on these stelae, which have since been set into the monastery courts walls, are inscriptions dating from 959 and 964 (ten and fifteen years after Yunmens death). They are the most important sources for Yunmens biography and also describe the original appearance of the monastery: