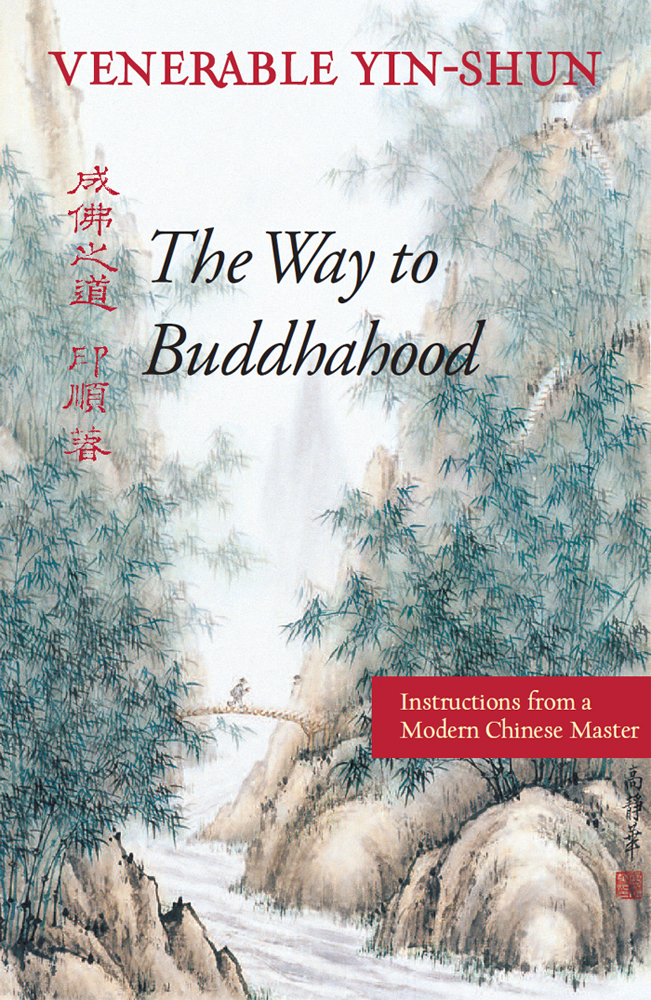

The Way to Buddhahood

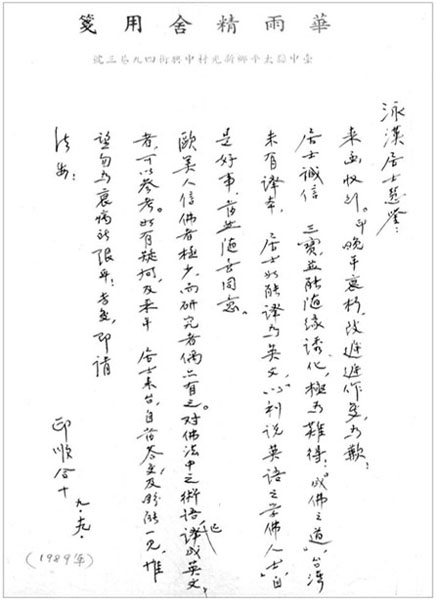

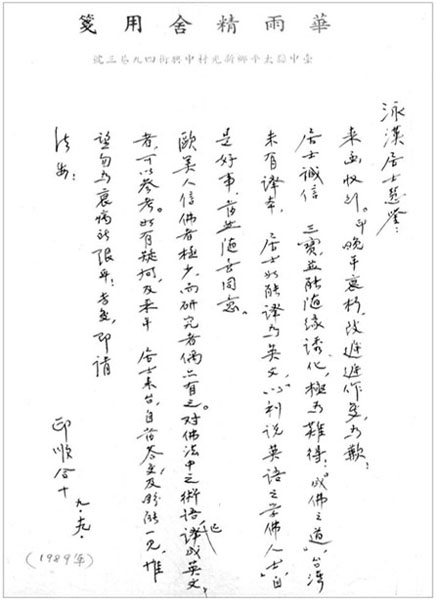

Handwritten letter by Master Yin-shun giving permission to Wing H. Yeung, M.D. to translate the book.

The Way

to Buddhahood

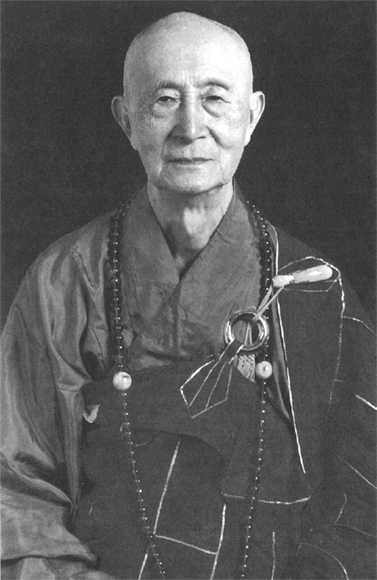

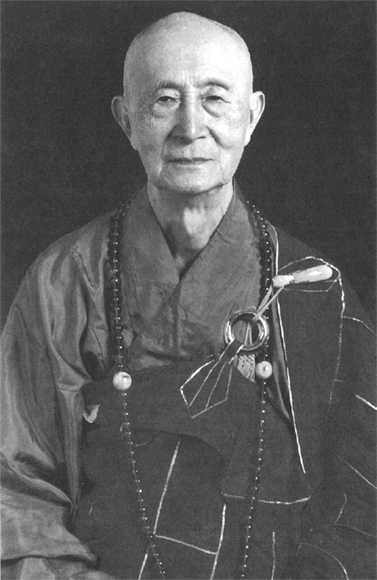

MASTER YIN-SHUN

Translated by Dr. Wing H. Yeung, M.D.

Foreword by Professor Robert M. Gimello

Introduction by Professor Whalen Lai

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

Venerable Yin-shun 1998, 2008

English translation Wing H. Yeung, M.D. 1998, 2008

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yin-shun.

[Cheng fo chih tao. English]

The way to buddhahood/ Yin-shun; translated by Wing Yeung.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86171-133-5 (alk. paper)

1. Buddha (The concept). 2. Buddhahood. 3. Mahayana Buddhism Doctrines. 4. Religious life Buddhism. I. Yeung, Wing. II. Title.

BQ4180.Y55 1998

294.3'4 dc21 9736370

ISBN 0-86171-133-5

09 08

7 6 5 4

Designe byTLrggms. Cover painting: Jing-hua Gao Dalia.

Contents

Table of Contents

Guide

Foreword

T HIS FINE TRANSLATION of one of Yin-shun Daoshis most widely read and influential works is a most welcome addition to the small English language archives of modern Chinese Buddhism.

Most western students of Buddhism have been woefully unaware of the extraordinary vitality of contemporary Chinese Buddhism, particularly as it has developed in post-war Taiwan. This has been especially lamentable in view of the fact that the foremost leader of Chinese Buddhisms intellectual resurgence, the monk Yin-shun, is both a scholar and an original thinker of the first order.

Among his many achievements is the renewal of mutually enriching connections between traditional Chinese Buddhism and the ancestral traditions of India, both the primordial Buddhism of the gamas (the northern counterpart of the Theravda stras) and the later Indian Mahyna traditions that had been so well preserved and advanced in Tibet.

Drawing thus upon the whole broad range of Buddhist thought but especially upon the Madhyamaka (Middle Way) tradition of Ngrjuna, Candrakrti, and Tsongkhapa Yin-shun has emphasized the rationalism and humanism of Buddhism while also bringing traditional Buddhist scholarship into invigorating dialogue with modern critical Buddhist Studies as practiced in the West and in Japan. In the course of these ground-breaking efforts he has done more even than his own master, the early twentieth century reformer Taixu, to rescue Chinese Buddhism from the intellectual doldrums and spiritual decay into which so much of it had fallen during the late imperial period of Chinese history. He has also plotted a course for Buddhisms future development that will allow its robust engagement with the modern world without forcing the severance of its traditional roots.

The Way to Buddhahood (Cheng fo zhi dao) presents itself as an introductory overview of the essentials of Buddhism, rendered in the traditional rhetorical modes of Buddhist doctrinal exposition. It is that, of course, but it is also much more. In it we see, not merely a summary of cardinal Buddhist concepts but also something of the rigorous and bold revisioning of Buddhism that Yin-shun has continued to develop in his many later and more specialized works. Thanks to Mr. Wing Yeungs very effective and trustworthy translation, readers of English may now begin to have access to this extraordinary mans ample body of work and to his powerful vision of the dharma.

Robert M. Gimello

Professor of East Asian Studies and Religious Studies

University of Arizona

Preface to the Chinese Edition

B UDDHISM IS A RELIGION of reason and not just a religion of faith. In explaining principles or instructing practices, Buddhist teachings rely on reason. These teachings are both rich and correct. Because the Buddha Dharma has always adapted to peoples different abilities and allowed free choice about which adaptation to follow, the teachings are diverse.

Two points will help people grasp the Buddha Dharma. First, the Buddhas teachings and the discourses of bodhisattvas and patriarchs vary according to peoples different capacities and preferences at different times and places. These variations exist in order to give different people appropriate guidance. Many skillful methods are used the easy and the profound, those pertaining to practices and those pertaining to principles. Some methods may seem to contradict one another. Viewing the different teachings is like peering into a kaleidoscope; beginners who are unable to integrate the views may feel perplexed.

Second, although the teachings are varied, all are interconnected. The different teachings start at different places, but each arrives at the others. This is like picking up a piece of clothing: whether one picks up a shirt by the collar, sleeve, or front, one gets the whole thing. Yet the adaptive characteristic of the Buddhist teachings, the different levels of difficulties, and the doctrinal interconnections are usually ignored. Instead, people tend to make generalizations and think that all teachings are similar.

These two opposing views that the teachings are too diversified or too similar can lead in the same direction. Some think that since the teachings are similar, one particular doctrine is equivalent to others. So they think that they do not need to practice and study extensively. Such thinking leads to the expansive development of the Dharma from a single stra, a single buddha, or a single mantra. Because such people are unable to grasp the Dharma completely, they abandon the ocean and take only one drop of water, which, they think, contains the whole ocean. On the other hand, some people exceedingly praise a doctrine which they more or less understand, thinking it is the best and the ultimate. Having this doctrine, they think that they have everything and need nothing else.

In sum, the Buddhist teachings are very diverse and befitting to all. Those who are unable to integrate and organize them systematically will make the mistake of taking only parts of them. In so doing they will abandon the whole. This style of practice has brought Buddhism to its present narrowness and poverty.

It is impossible to expect all devotees to integrate and organize the Buddha Dharma in their practice. Those who propagate the Buddhist teachings should have a superior understanding of them, however. Only then will they be able to expound the Dharma and maintain its integrity without becoming confused and biased.

In this regard, the Tiantai tradition and the Xianshou tradition (also known as the Huayan School) have done good work. The masters of these traditions have integrated the Buddhist teachings and organized them into courses with graduated practices. These courses demonstrate both the differences among the various doctrines and the relationships between them. It is no wonder that in the past those who taught the Dharma followed either the four modes of teaching of the Tiantai tradition or the five modes of teaching of the Xianshou tradition. Both of these place great emphasis on the perfect teaching; directly entering the perfect teaching is their objective.

Next page