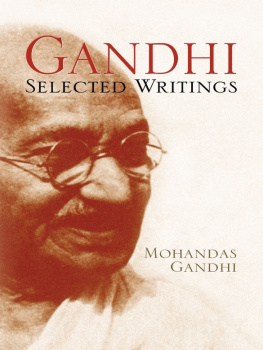

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in Porbander. He was called to the Bar. He was not very successful as a Barrister-at-law in India and he moved to South Africa in 1893. In South Africa, he was unable to accept the official policy of racial discrimination and launched a series of non-violent protests.

On the basis of his South African experience, Gandhi elaborated a critique of Western civilization and a theory of passive resistance. In India he began his political career by organizing protests against the oppressive Rowlatt Act and by the peaceful mobilization of peasants in Champaran in Bihar and in Kheda in Gujarat. He was the key figure in the three great mass movementsthe Non-Co-operation Movement (192022), the Civil Disobedience Movement (193132) and the Quit India Movement (1942)which were the most important milestones in Indias struggle for freedom. He was a champion of handspun cloth, Hindu-Muslim unity and the removal of untouchability. Non-violence remained right through his life the first article of his creed.

Gandhi chose to absent himself from the celebrations in New Delhi which marked Indias independence on 15 August 1947. He could not accept the two nation theory and its logical sequel, the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan.

He was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic on 30 January 1948 while he was addressing a prayer meeting.

Rudrangshu Mukherjee was born in 1952 and educated at Presidency College, Calcutta, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi and St Edmund Hall, Oxford. He was awarded a D.Phil. in Modern History in 1981 by the University of Oxford. He is the author of AwadhinRevolt185758:AStudyofPopularResistance; and an editor of TradeandtheIndianOceanWorld:EssaysinHonourofAshinDasGupta.

Introduction

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 at Porbander in the western coast of India. His father was an official of a small native state. He had an orthodox upbringing but went to London to train as a lawyer. He enrolled at the Inner Temple and was called to the Bar in the summer of 1891. Back in India, he could not make a successful career as a lawyer and moved to South Africa in 1893. Confronted with the rampant racism in vogue there, he began the first of, what he was to call later, his experiments with truth. The main thrust of this experiment was to resist racial discrimination non-violently. It involved the peaceful violation of certain laws, the courting of arrests collectively, hartals and spectacular marches.

The South African experiment was to serve as a model of Gandhis involvement in mass movements in India. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Indian National Congress and the Indian national movement was in disarray. In the aftermath of the swadeshi movement in Bengal, the Indian National Congress was split between Moderates and Extremists. There was, however, a growing awareness in the country of the various dimensions of imperialist exploitation and oppression. It was in this atmosphere that Gandhi made his first mark in Indian politics by organizing mass, non-violent protests in Champaran, Kheda and against the Rowlatt Act.

But before his emergence in the Indian political scene, Gandhi had already worked out some of his fundamental ideas. He articulated these in a booklet called HindSwaraj. All commentators on Gandhi recognize this to be the most coherent exposition of Gandhis world-view.

HindSwaraj is a trenchant critique of modern civilization but it also contains a statement of Gandhis alternative to modern civilization and a programme for Indians to actualize such an alternative. Gandhi was emphatic about the superiority of Indian civilization and its inherent ability to withstand the onslaughts of modernity. Throughout his life, in all his major writings, Gandhi returned again and again to these themes.

The critique attacked all the major aspects of the modern philosophy of life,Gandhi emphasized that it was called Western because its principal site was the West. had Gandhis approval. From Lev Tolstoys political writings Gandhi took his ideas about the essentially repressive character of the State and about the moral imperative of non-violence. There is always the danger while discussing the lineages of Gandhis ideas of overemphasizing the influences. Gandhi was thoroughly eclectic and his borrowings were not impaired by any considerations of scientific and theoretical rigour. Thus, while Gandhi borrowed from Ruskin and Carpenter, he rejected completely some other aspects of their thought. This distinguished Gandhi from the romantic critique of capitalism. Carpenter, for example, argued, drawing, in his own turn, from Lewis Morgan and Engels, that civilization transformed the nature of property and thereby destroyed mans unity with nature. Such theories did not attract Gandhi.

Ruskin, again, was a historicist influenced by German idealism especially by Hegel. He was also a believer in the virtues of modernity caring intensely, as R.G. Collingwood noted, for science and progress, for political reform, for the advancement of knowledge and for new movements in art and letters.

This was, of course, completely unacceptable to Gandhi. He did not share this confidence in Reason and Science. He asserted that the scientific mode of knowledge was applicable only to very limited areas of human living. The assumption that rationality and science could provide solutions to all problems led to insanity and impotence.... mere intellect, Gandhi wrote, makes one insane or unmanly.... The reasoning faculty will raise a thousand issues. Only one thing will save us from these and that is faith.

Gandhi thus not only made a critique of modern civilization, civil society and its various institutions; the intellectual developments associated with modern civilizationReason, Science, History, the dominant themes of post-enlightenment thoughtmet with his utter and complete disapproval and rejection. This rejection gave his arguments a uniquely self-contained character. The epistemic vantage point for Gandhi was outside civil society and post-enlightenment thought. Unlike the romantics his critique was not an elaboration of the historical contradictions of civil society as comprehended from within it.

Thus the alternative to modern civilization that Gandhi posed had to be located outside the domain of civil society and the influences of modern civilization. And India was uniquely placed to provide this alternative, indeed, only India could provide the alternative since millions of Indians who lived in the villages had not been lured by the trappings of modern civilization.

Real civilization was to be found in the villages of India. The traditional village world, autonomous of modern civilization, was the complete opposite of the individualistic world of civil society. Life was governed by a communal morality where each member performed his duty. It was to the common people living independently that Gandhi turned: India, to me, he wrote, means its teeming millions on whom depends the existence of its princes and our own. The hope of India lay in the peasantry.