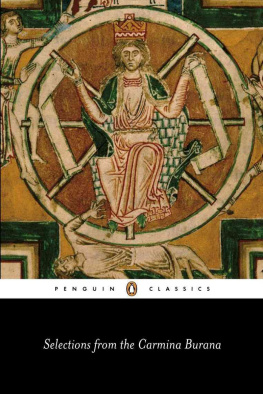

SELECTIONS FROM THE CARMINA BURANA ADVISORY EDITOR: BETTY RADICE David Parlett was born in London in 1939, educated at Battersea Grammar School and took his degree in Modern Languages at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. He was a teacher, a technical journalist and then in public relations before establishing himself as a freelance author and games-inventor. In this capacity he is an acknowledged expert on the history of card games and the author of three Penguin originals: Card Games, Patience and Word Games. His interest in translating the Carmina Burana is of many years standing and results inevitably from a conjunction of interests in history, poetry and linguistics. Even the games interest is relevant, he asserts, pointing to the example of J. D.

SELECTIONS FROM THE CARMINA BURANA ADVISORY EDITOR: BETTY RADICE David Parlett was born in London in 1939, educated at Battersea Grammar School and took his degree in Modern Languages at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. He was a teacher, a technical journalist and then in public relations before establishing himself as a freelance author and games-inventor. In this capacity he is an acknowledged expert on the history of card games and the author of three Penguin originals: Card Games, Patience and Word Games. His interest in translating the Carmina Burana is of many years standing and results inevitably from a conjunction of interests in history, poetry and linguistics. Even the games interest is relevant, he asserts, pointing to the example of J. D.

Huizinga, whose Homo Ludens and The Waning of the Middle Ages are classics in their respective fields. David Parlett is married and lives in South London with his wife and two children.

David Parlett

SELECTIONS FROM THE

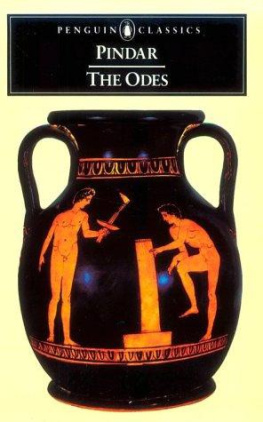

CARMINA BURANA

A VERSE TRANSLATION Penguin Books PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, lreland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published 1986 Copyright David Parlett, 1986 All rights reserved Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser ISBN: 978-0-14-196080-7

To Norah GrangerGaude quod primam te sors mihi fecit amicamCONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Outside a specialized readership

Carmina Burana is probably best known as the title of a popular work for chorus and orchestra by Carl Orff. The hour-long cantata, much performed and recorded, is an exuberant setting of some twenty poems in Medieval Latin and Middle High German from a thirteenth-century manuscript found at Benediktbeuern in Bavaria (whence the title, Songs of Beuern). They are essentially secular pieces, of varying degrees of literary merit, and covering a range of themes including satire, literary and liturgical parody, love songs, drinking songs and stories from the classics. As the largest and most varied surviving anthology of Medieval Latin poetry, the manuscript represents the last outpourings of poets who still used the language as fluently as their native tongues.

The present selection originated in a desire to provide an intelligible English text to the cantata: one that would follow the same metrical and rhyming patterns as the Latin, and so be singable to Orffs tunes. The result proved too short for independent publication, and I was invited to essay a larger collection drawn from the whole manuscript. This proved a welcome, if daunting, invitation; for although the popularity of the music at least puts the text into the public consciousness, the cantatas comparative brevity and contrived dramatic form tend to obscure the size, nature and importance of its literary source. Carl Orff necessarily restricted himself to about twenty pieces from a total of some 350 (depending on how they are counted). Many of his settings are of selected extracts from longer poems whose tenor, when considered as a whole, does not always accord with those portions emanating from the concert hall. If we add that he worked from editions of the text which have since been corrected in many important respects (and take into account various other criticisms of an extra-musical nature) it becomes understandable why Orff has not endeared himself to latter-day medieval scholars, who tend to regard the text not just as sacrosanct but as private property to boot.

Apart from a manuscript facsimile, the Carmina Burana has never been published as a whole in an English edition, and such parts of it as have already been done into English to borrow Omar/Fitzgeralds felicitous phrase are scattered through various publications not now easy to come by. In making my selection, which in terms of linage represents about 2025 per cent of the whole, I have been guided by two complementary and sometimes conflicting considerations. One was a desire to reflect the variety of the original collection by covering as many different genres and subjects as possible, even if some are of little intrinsic literary merit or seem out of joint with modern preoccupations. The other was a need to concentrate on those pieces most amenable to a fairly literal line-by-line treatment in English verse without having to wander too far from the poets chosen form, or from my understanding of his intentions. Compromise has been inevitable. In some cases I have attempted the impossible for the sake of being representative; in others I have rejected the intractable for fear of being inaccurate.

I also wished to cater both for those whose only knowledge of the Carmina Burana is the cantata by Orff and for those who feel that his idiosyncratic concert selection does the original a disservice. I have therefore included in their entirety all the pieces which the composer used either wholly or in part, and gathered together in an appendix an English-language version of the concert selection so that it may be followed separately if required.

Language

Although none is named in the manuscript, some of the authors have been identified through other sources. They prove to have been of various nationalities, and hence native speakers of various tongues including English, French, German and other vernaculars of the time. They wrote in Latin because at the time of composition literacy was synonymous with Latinity. To read and write was by definition to read and write Latin and to speak it, think in it, perchance to dream in it as well.

It was the international language of western Europe and the Church or of Christendom, to combine two modern concepts in one medieval term. Learning was traditionally a function of the religious life, and such education as there was lay in the hands of the Church and the monasteries. The first step in education was necessarily the acquisition of Latin, since it was the everyday medium of instruction for everything that followed. As a spoken language, Medieval Latin differed significantly from the over-refined medium of the classical authors, from which it does not stand in true line of descent. Though a subtle and versatile literary vehicle in its own right, it may be traced back rather to the everyday spoken language of the Roman people (Vulgar Latin) as employed by early Christian users, who found themselves unable to spread the word if the word was one which only the educated classes could understand. (A man who is asking God to forgive his sins, said St Augustine, does not much care whether the third syllable of

SELECTIONS FROM THE CARMINA BURANA ADVISORY EDITOR: BETTY RADICE David Parlett was born in London in 1939, educated at Battersea Grammar School and took his degree in Modern Languages at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. He was a teacher, a technical journalist and then in public relations before establishing himself as a freelance author and games-inventor. In this capacity he is an acknowledged expert on the history of card games and the author of three Penguin originals: Card Games, Patience and Word Games. His interest in translating the Carmina Burana is of many years standing and results inevitably from a conjunction of interests in history, poetry and linguistics. Even the games interest is relevant, he asserts, pointing to the example of J. D.

SELECTIONS FROM THE CARMINA BURANA ADVISORY EDITOR: BETTY RADICE David Parlett was born in London in 1939, educated at Battersea Grammar School and took his degree in Modern Languages at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. He was a teacher, a technical journalist and then in public relations before establishing himself as a freelance author and games-inventor. In this capacity he is an acknowledged expert on the history of card games and the author of three Penguin originals: Card Games, Patience and Word Games. His interest in translating the Carmina Burana is of many years standing and results inevitably from a conjunction of interests in history, poetry and linguistics. Even the games interest is relevant, he asserts, pointing to the example of J. D. A VERSE TRANSLATION Penguin Books PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, lreland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published 1986 Copyright David Parlett, 1986 All rights reserved Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser ISBN: 978-0-14-196080-7 To Norah GrangerGaude quod primam te sors mihi fecit amicam

A VERSE TRANSLATION Penguin Books PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, lreland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published 1986 Copyright David Parlett, 1986 All rights reserved Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser ISBN: 978-0-14-196080-7 To Norah GrangerGaude quod primam te sors mihi fecit amicam