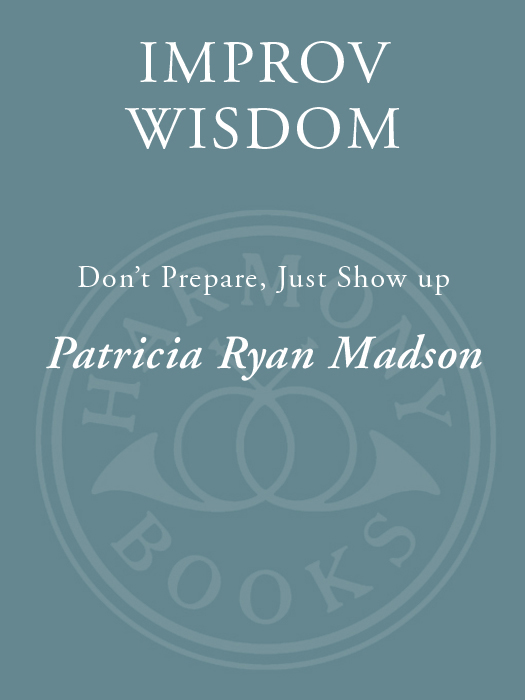

For Mama,

Virginia Louise Pittman Ryan

19201998

She always said yes.

______

For my husband,Ronald Whitney Madson

My improv partner in life

It delights me to acknowledge my deep gratitude

to the four decades of students who have shown up for my classes,

and

who tried all the crazy things I recommended.

It is thanks to each of you that I have had

the greatest job in the world

being a teacher.

[contents]

[the first maxim]

say yes

[the second maxim]

dont prepare

[the third maxim]

just show up

[the fourth maxim]

start anywhere

[the fifth maxim]

be average

[the sixth maxim]

pay attention

[the seventh maxim]

face the facts

[the eighth maxim]

stay on course

[the ninth maxim]

wake up to the gifts

[the tenth maxim]

make mistakes, please

[the eleventh maxim]

act now

[the twelfth maxim]

take care of each other

[the thirteenth maxim]

enjoy the ride

There are two kinds of intelligence: one acquired, as a child in school memorizes facts and concepts from books and from what the teacher says, collecting information from the traditional sciences as well as from the new sciences.

With such intelligence you rise in the world. You get ranked ahead or behind others in regard to your competence in retaining information. You stroll with this intelligence in and out of fields of knowledge, getting always more marks on your preserving tablets.

There is another kind of tablet, one already completed and preserved inside you. A spring overflowing its springbox. A freshness in the center of the chest. This other intelligence does not turn yellow or stagnate. Its fluid, and it doesnt move from outside to inside through the conduits of plumbing-learning.

This second knowing is a fountainhead from within you, moving out.

R UMI , T WO K INDS OF I NTELLIGENCE , translated by Coleman Barks

[prologue]

When I was eleven years old and living in Richmond, Virginia, my mother bought me a paint-by-numbers kit. The subject was a leafy maple tree. I loved the silky feel of the brushes, the touch of the textured canvas, and the oily smell of the paints. I painted carefully, always getting the prescribed colors just right, critical if I went over a line even slightly. My formula painting seemed beautiful to me, and my father declared proudly: Patsy is an artist. Other kits followed, and I faithfully continued to paint inside the lines.

I had found the way to live: Always go by the rules. Use the recipe. Follow the pattern. Rehearse the script. Copy the masters. I followed the lines in everything I did, even though I considered myself an artist, a theater artist at first. With theater, you were given your lines, and all you had to do was bring them to life. That seemed easy. I went to study at Wayne State University to get a graduate degree so that I could teach. After three years with the Hilberry Classic Repertory Company and several hundred performances, I moved on to accept an assistant professorship at Denison University in Ohio, teaching acting. I longed to be normal and have a dependable and ordinary life. I rented a house perched on a hill in Granville, Ohio, began collecting furniture and art, and cultivated a coterie of university friends and colleagues.

This was the job of my dreams. I had a regular (albeit modest) paycheck, generous benefits, the prestige of being a professor, long holidays, and the security of being part of a small college family. My one goal in life was to make that dream permanentand the way to do that was to gain tenure. I studied the politics of the university and volunteered for any task that would look good on my academic rsum. I chaired the Governance Review Commission. I took on a prestigious assignment as Denisons regional director for the Great Lakes Colleges Association New York Arts Program. I allied myself with the right people. I taught nine different classes in my department, volunteering to fill any void that appeared in the curriculum. I was popular and, in my fifth year, won a university prize for excellence in teaching. My rsum of college service, professional activity, and classroom experience seemed flawless. The tenure review came, and my interviews went well. I was all set to put a down payment on a home in Granville when the decision was announced.

Sorry

The notification letter thanked me for my considerable service and informed me that my teaching lacked intellectual distinction. This made no sense to me, since I had recently won a teaching award, had chosen each career move to impress the academy, and had done everything by the book. I had painted inside the lineswell. So where had I gone wrong?

I had never taken a chance. I had not once followed an impulse or listened to the beat of my own drum. Poloniuss instruction To thine own self be true flashed in mind. I had not been true to my self. It had not occurred to me that there was another way of living that did not require a script. To find that way I would need to learn to listen to and trust myself. (The real discovery came years later when I understood that I had to trust something greater than myself.)

I had tried to be worthy of receiving tenure. I didnt understand that this worthiness could come only from honoring my own voice. Making decisions solely to please others is a formula destined to fail. The people I admired were not looking over their shoulders to see if their peers were applauding. They were heeding their inner promptings. I do this because I know it needs to be done. My search for validation had diverted me from discerning what was uniquely mine.

Denison was right to let me go. Once I had been denied tenure I imagined my academic career to be finished and that it would be unlikely for me to find another university job. I was wrong, fortunately. Before I had even served out a lame-duck year, the chairman of Penn State Universitys lively theater program offered me an assistant professorship, teaching acting and voice. Someone had left a position on short notice, and I was a qualified candidate. I was overjoyed to have been given another chance.

I promised myself that whatever happened I would never again make choices simply to impress others or to gain status. I would listen to my own drum and march to it. And while I was commonly clumsy with the sticks, I began drumming, so to speak. I gave up doing things for my rsum. I took up tai chi and spent summers dancing and traveling, studying Eastern religion and expanding my vision of life. My view of theater was no longer bounded by the proscenium arch. I was drawn to the anthropology of acting, and I began to explore, dream, and act. I opened my eyes, looked around, and said yes. I didnt know it at the time, but I was becoming an improviser, learning to listen and to trust my imagination.

Two years later Stanford University enticed me away from Penn State by offering me the job of heading up their undergraduate acting program. It seems no accident that my academic life began to flower at the same time I was exploring this valuable life lesson of improvisation. California was where I needed to be, and in the summer of 1977, in a rusty mint green Mercury Marquis Brougham with shiny brocade seats, I drove across the United States to accept my exciting position on the Farm.