City of Saints

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

City of Saints

Rebuilding Rome in the Early Middle Ages

Maya Maskarinec

This book is made possible by a collaborative grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Copyright 2018 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Maskarinec, Maya, author.

Title: City of saints : rebuilding Rome in the early Middle Ages / Maya Maskarinec.

Other titles: Middle Ages series.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Series: The Middle Ages series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046025 | ISBN 978-0-8122-5008-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Christian saintsCultItalyRomeHistoryTo 1500. | ChristianitySocial aspectsItalyRomeHistoryTo 1500. | ChristianitySocial aspectsEuropeHistoryTo 1500. | Rome (Italy)Church history. | Rome (Italy)History4761420.

Classification: LCC BX2333 .M38 2018 | DDC 235/.2094563209021dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046025

Contents

Color plates follow

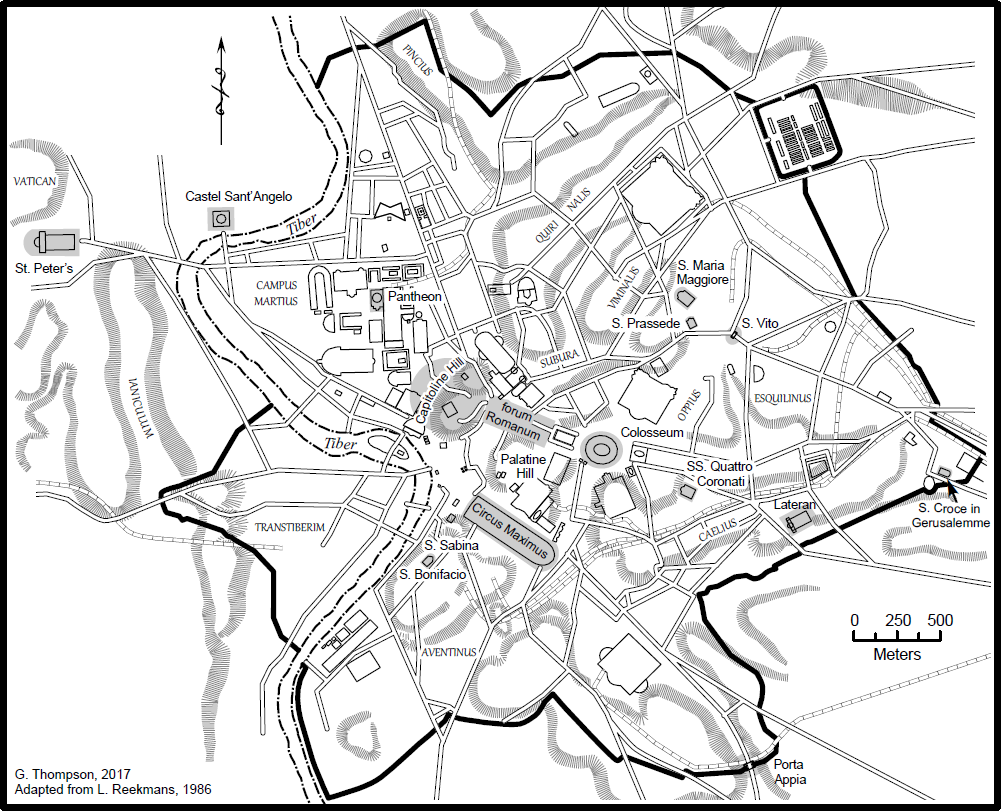

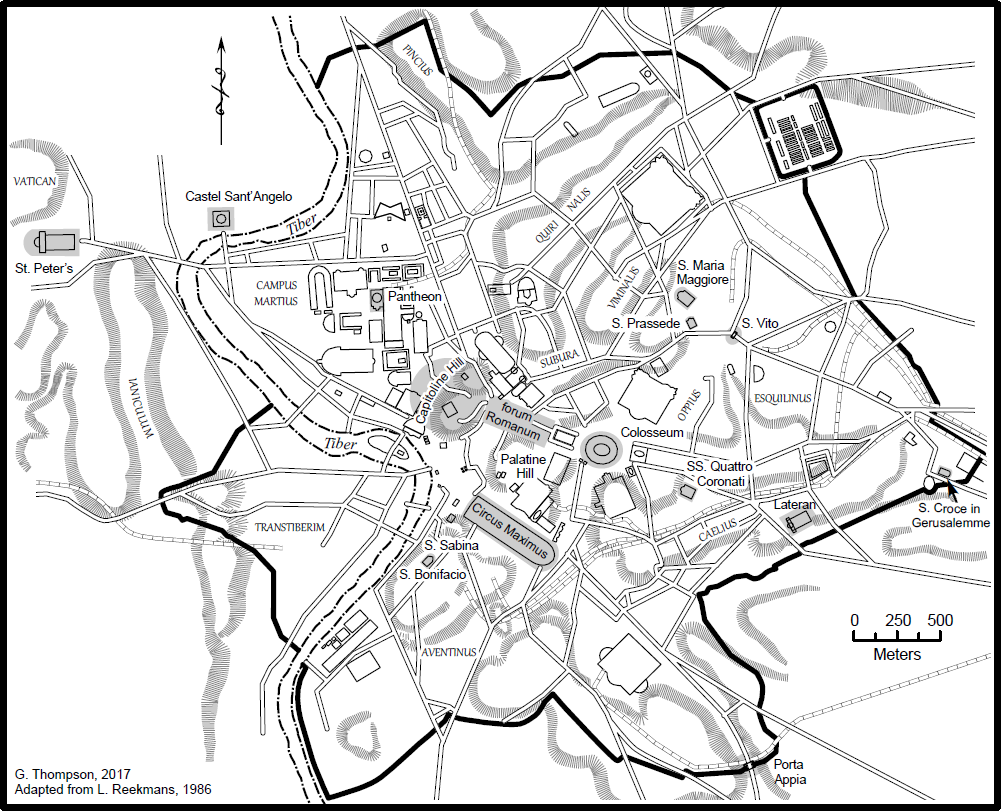

Map 1. Map of early medieval Rome. Map adapted by Gordie Thompson after Reekmans, Limplantation monumentale chrtienne.

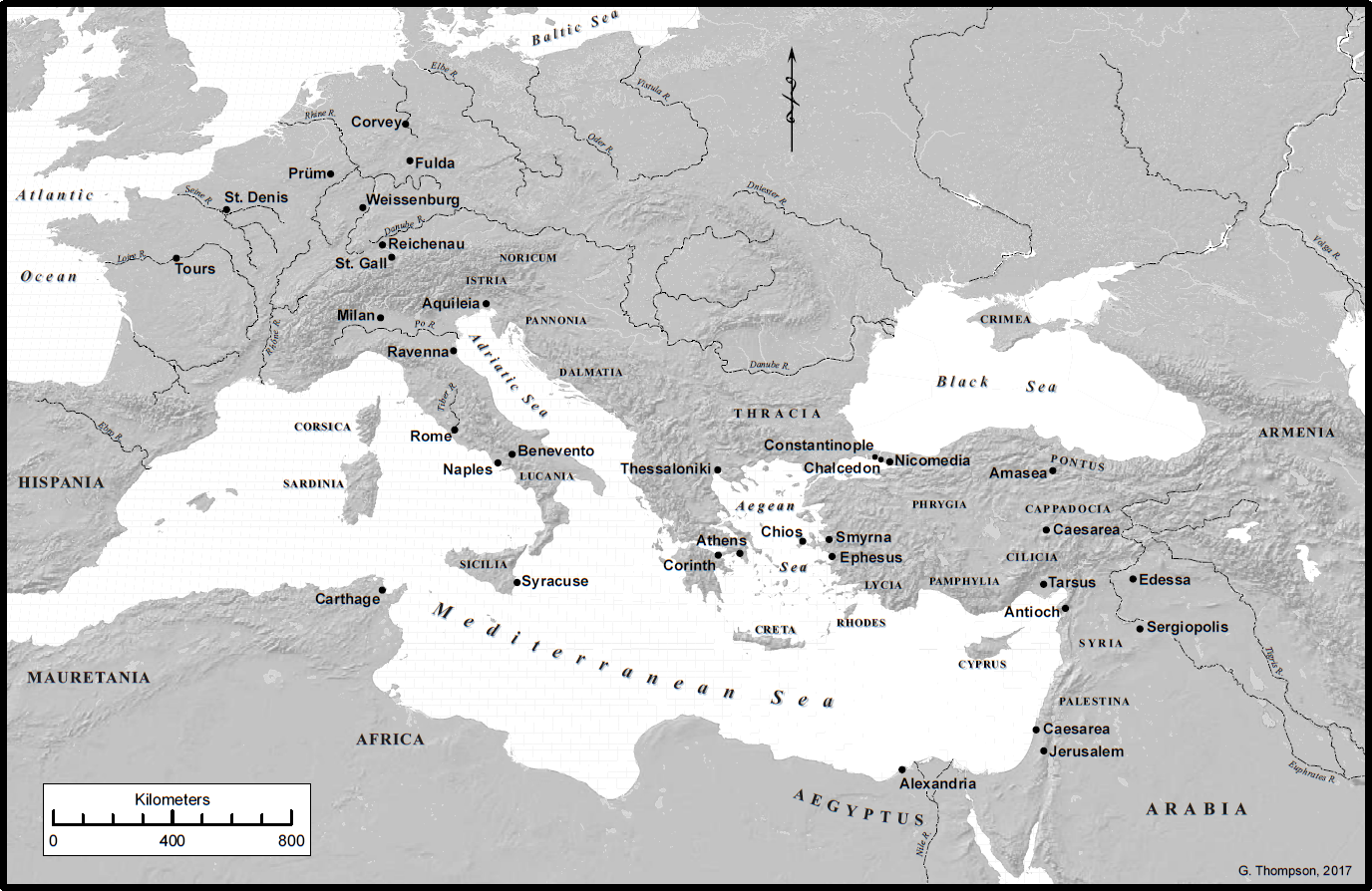

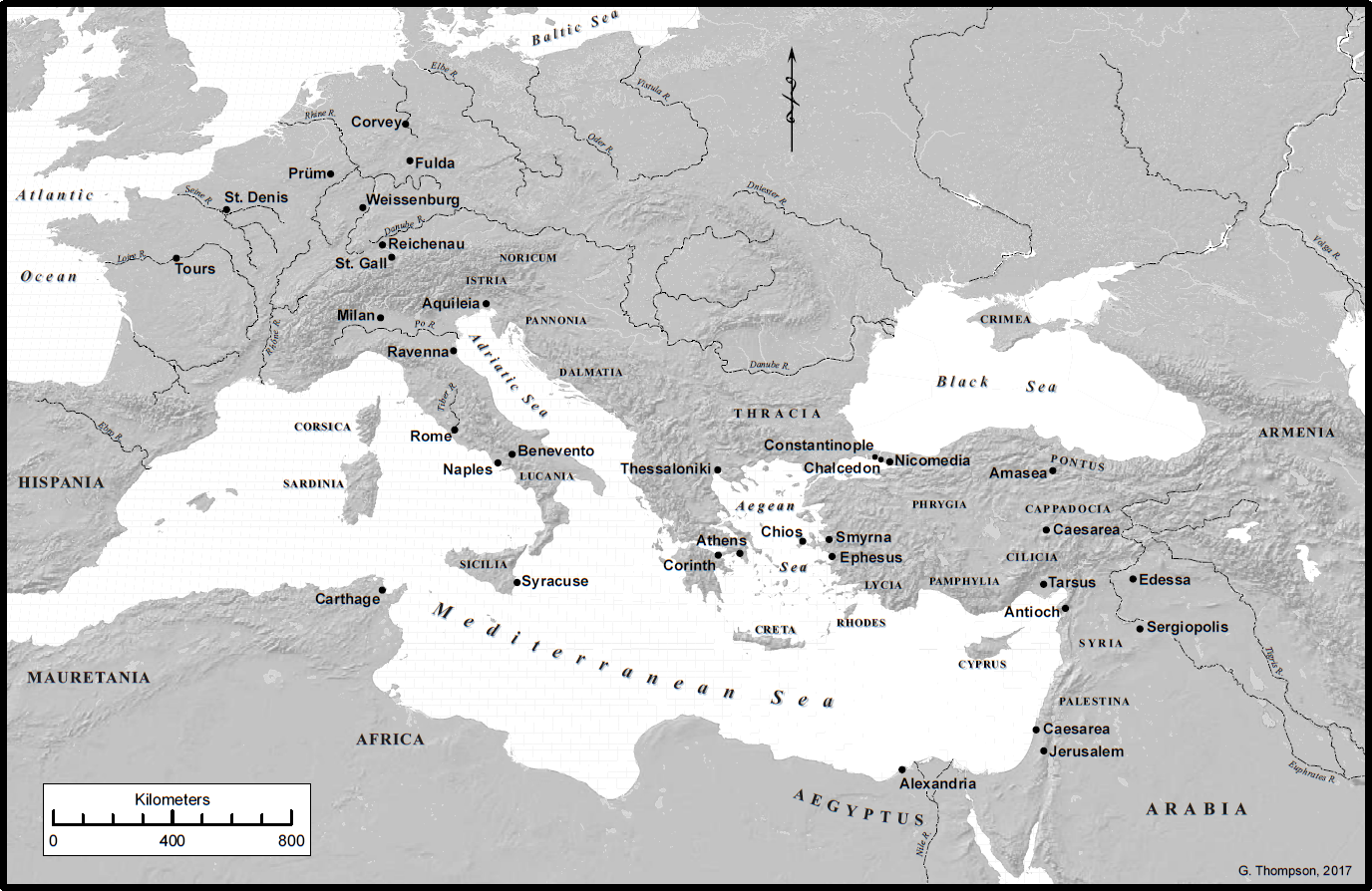

Map 2. Map of the early medieval Mediterranean. Map created by Gordie Thompson.

In the mid-eighth century, Fulrad, abbot of the monastery of St. Denis, north of Paris, was burning with great enthusiasm to serve God by rendering due honor to the most blessed Christian martyrs. They returned having succeeded in their mission: Fulrad, with the bodies of the saints Alexander and Hippolytus, martyred in Rome; his relative, with that of St. Vitus, martyred, according to legend, in southern Italy, in Lucania, under the Roman emperor Diocletian.

It is easy to take for granted Fulrads enthusiasm for Rome. The Carolingian fascination with Rome, ancient and Christian, is well documented. But it was not: Romes ability to reinvent itself in countless guises over the centuries was neither predictable nor inevitable.

Yet, eighth-century Rome remained a monumental city with traces of its former imperial glory on view. But Rome also had something moreanother ingredient that acted as a catalyst to its remarkable transformation from a crumbling city with an imperial and Christian past to the spiritual capital of western Christendom. This feature inspired Fulrads journey to Rome.

Rome in the early eighth century, as part of the Byzantine Empire, was shaped by its interactions with the wider Mediterranean world; it was also a city turning to face north of the Alps. As a Mediterranean city, Rome housed saints, like Vitus, who were venerated, but not martyred, in Rome. These were saints whose cults had spread throughout the Mediterranean world but were not necessarily well known in the Frankish kingdoms or other communities north of the Alps. Eastern merchants, travelers, and refugees brought stories and relics of such saints to Rome, and in Rome, Roman administrators, ecclesiastics, and aristocrats actively participated in their cults. Adapted to Romes multilayered imperial and Christian past, these new saints and their communities contributed to the citys dynamic sacred topography, magnifying Romes allure to audiences north of the Alps. These saints and their communities are the missing ingredient that explains why Rome became the prime Carolingian destination for serving God with enthusiasm.

It argues that these saints were critical to Romes remarkable metamorphosis, against all odds, from an exhausted city with a limited Christian presence to a city filled with a seemingly inexhaustible reservoir of sanctity.

The period under study here, roughly the sixth to the ninth centuries, is commonly referred to as the early Middle Ages. It has also been called the Dark Ages, a description that does accurately reflect the paucity of surviving evidence. As their names suggest, the early Middle Ages and its counterpart, Late Antiquity (roughly the third to the sixth centuries), are periods that fall between the cracks of the traditional historical periodizations of Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Yet, scholarly work in the past fifty years, above all that of Peter Brown, has dispelled the notion of Late Antiquity as a break in history. This prompts the question of what happened next: how did Rome develop in new ways out of its late antique heritage?

Studying saints from abroad in Rome provides us insight into this transformation. There was nothing intrinsically different about how or why saints from abroad were venerated in the city in comparison with the veneration of saints martyred in Rome. Both types of saints provided patronage and protection to their communities. And yet, it is instructive to focus on the category of saints from abroad for two principal reasons.

First, patchy and often unsatisfactory as the evidence is, such an approach complicates our static picture of the early medieval city. It wrenches us away from the myth of the inevitable rise of a Rome destined for Christian primacy, shepherded through the Dark Ages by powerful popes. By attending to the less studied evidence of saints cults from abroad, we begin to hear a vibrant plurality of voicesof Byzantine administrators, refugees, monks, pilgrims, and othersas well as ecclesiastics, enmeshed in a wider world stretching across the Mediterranean and western Europe. Unexpected and unintended as their actions were, these individuals were as vital as any early medieval pope in shaping the saintly topography of Rome.

Wherever a saint went, he or she bore this geographical marker, evoking a world beyond the confines of the saints new community.

In Rome, the presence of these saints gave particular inflexion to the city, rendering it more than just another localized community. (

Saints were an integral part of late antique and early medieval Christendom. The essence of an individuals sanctity was his or her virtus, virtue, which rendered a saint closer to God than other mortals. Holy men and women were recognizable by their exemplary ways of life or feats of endurance; martyrs had secured their place in heaven by dying for the faith. Saints were intercessors between heaven and earth, offering assistance and protection, physical and spiritual, to the men and women who invoked them in their prayers. Saints had the ability to perform signs and miracles. Relics, the living remains of deceased saints, perpetuated their presence on earth.