Contents

About the Book

What do you and an ancient philosopher have in common? It turns out much more than you might think

Aristotle was an extraordinary thinker, perhaps the greatest in history. Yet he was preoccupied by an ordinary question: how to be happy. His deepest belief was that we can all be happy in a meaningful, sustained way and he led by example.

In this handbook to his timeless teachings, Professor Edith Hall shows how ancient thinking is precisely what we need today, even if you dont know your Odyssey from your Iliad. In ten practical lessons we come to understand more about our own characters and how to make good decisions. We learn how to do well in an interview, how to choose a partner and life-long friends, and how to face death or bereavement.

Life deals the same challenges in Ancient Greece or the modern world. Aristotles way is not to apply rules its about engaging with the texture of existence, and striding purposefully towards a life well lived.

This is advice that wont go out of fashion.

About the Author

Edith Hall first encountered Aristotle when she was twenty, and he changed her life forever. Now one of Britains foremost classicists, and a Professor at Kings College London, she is the first woman to have won the Erasmus Medal of the European Academy. In 2017 she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Athens University, just a few streets away from Aristotles own Lyceum.

She is the author of several books, including Introducing the Ancient Greeks. She lives with her family in Cambridgeshire.

Also by Edith Hall

The Ancient Greeks: Ten Ways They Shaped the Modern World

Timeline (all dates BCE )

| 384 | Aristotle is born in Stageira to Nicomachus and Phaestis. |

| c.372 | Aristotles father dies and he is adopted by Proxenus of Atarneus. |

| c.367 | Aristotle moves to Athens to study at Platos Academy. |

| 348 | Philip II of Macedon destroys Stageira but rebuilds it on Aristotles request. |

| 347 | Aristotle leaves Athens when Plato dies and joins Hermias, ruler of Assos. |

| 345344 | Aristotle conducts zoological research on Lesbos. |

| 343 | Philip II invites Aristotle to teach his son Alexander in Macedon. |

| 338336 | Aristotle may have spent time in Epirus and Illyria. |

| 336 | Philip II is assassinated and Alexander becomes King Alexander III (the Great). Aristotle moves to Athens and founds his Lyceum. |

| 323 | Alexander III dies in Babylon. |

| 322 | Aristotle is prosecuted for impiety at Athens and moves to Chalkis, where he dies. |

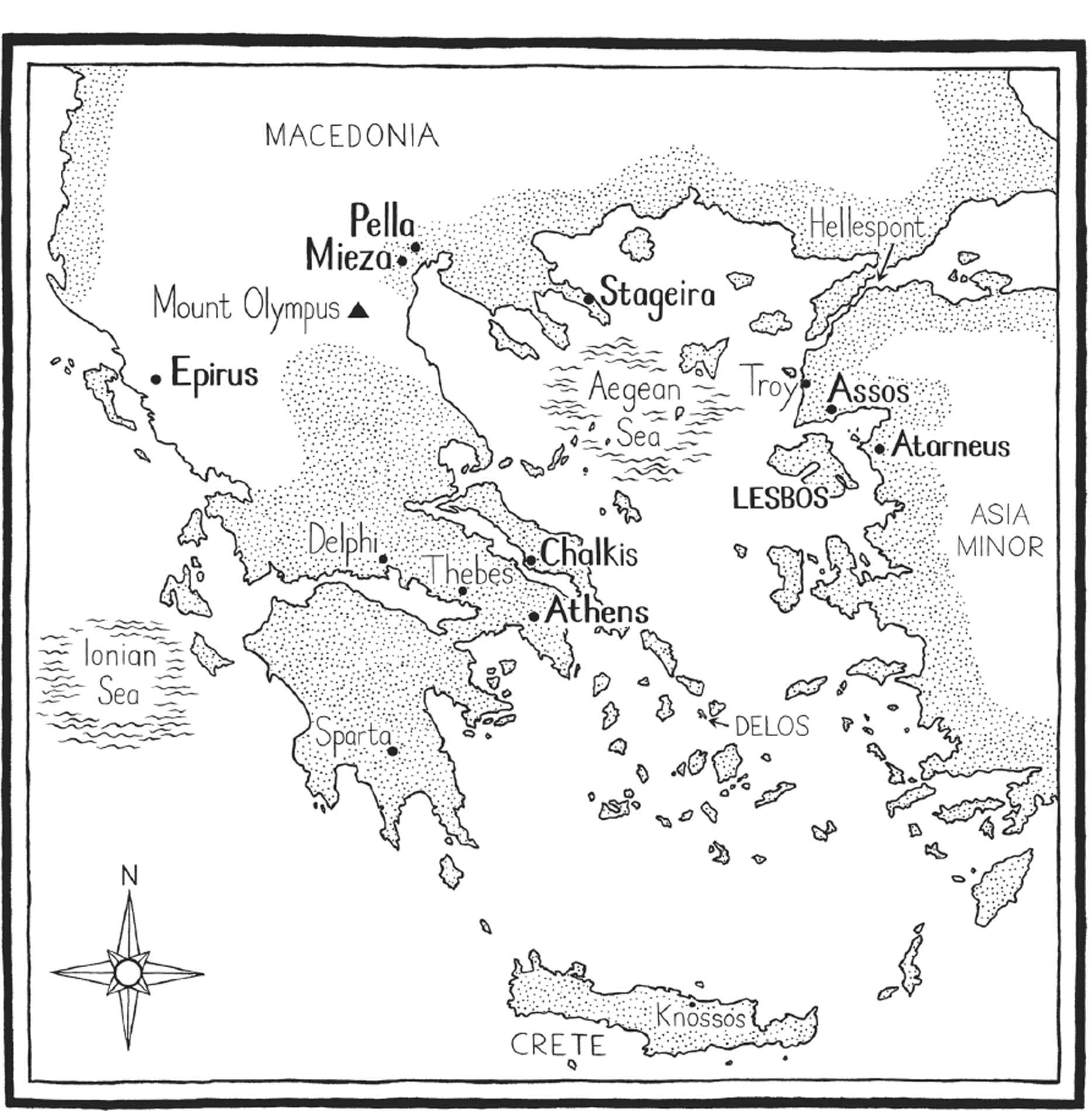

Map showing in bold places where Aristotle lived. The dotted areas indicate the Greek-speaking world of the fourth century BCE .

This book is dedicated to the memory of Aristotle the Stageirite, son of Nicomachus and Phaestis

Introduction

THE WORDS HAPPY and Happiness work hard. You can buy a Happy Meal, or drink a cheap cocktail during happy hour. You can pop happy pills to improve your mood or post a happy emoji on social media. We value happiness highly. Singer Pharrell Williams song Happy was number one and the bestselling song of 2014 in the United States, as well as twenty-three other countries. Happiness, according to Williams, was a transitory moment of elation, or feeling like a hot-air balloon.

Yet we are confused about happiness. Almost everyone believes that they want to be happy, which usually means a lasting psychological state of contentment (despite what Williams sings). If you tell your children that you just want them to be happy, you mean permanently. Paradoxically, in our everyday conversations, happiness far more often refers to the trivial and temporary glee of a meal, cocktail, email message. Or, as Lucy in the Peanuts comic strip put it after hugging Snoopy, an encounter with a warm puppy. A happy birthday is a few hours of enjoyment to celebrate the anniversary of your birth.

What if happiness were a lifelong state of being? Philosophers are divided into two main camps about what that would actually mean. On one side, happiness is objective, and can be appreciated, even evaluated, by an onlooker or historian. It means having, for example, good health, longevity, a loving family, freedom from financial problems or anxiety. According to this definition, Queen Victoria, who lived to over eighty, gave birth to nine children who survived into adulthood and was admired around the world, had a clearly happy life. But Marie Antoinette was clearly unhappy: two of her four children died in infancy, she was reviled by her people and executed while still in her thirties.

Most books about happiness refer to this objective well-being definition, as do the studies set up by governments to measure the happiness of their citizens on an international scale. Since 2013, on 20 March every year the United Nations has celebrated the International Day of Happiness, which seeks to promote measurable happiness by ending poverty, reducing inequality and protecting the planet.

But on the other side are philosophers who reject this, and instead understand happiness subjectively. To them, happiness is not akin to well-being but to contentment or felicity. According to this view, no onlooker can know if someone is happy or not, and it is possible that the most outwardly boisterous person might be suffering from deep melancholy. This subjective happiness can be described, but not measured. We cannot assess whether Marie Antoinette or Queen Victoria was happier for a greater proportion of her time alive. Perhaps Marie Antoinette enjoyed long hours of intense gratification, and Victoria never did, having been widowed early and having lived for years in seclusion.

Aristotle was the first philosopher to enquire into this second kind of subjective happiness. He developed a sophisticated, humane programme for becoming a happy person, and it remains valid to this day. Aristotle provides everything you need to avoid the realisation of the dying protagonist of Tolstoys The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), that he has wasted much of his life scaling the social ladder, and putting self-interest above compassion and community values, all the while married to a woman he dislikes. Facing his imminent death, he hates his closest family members, who wont even talk to him about it. Aristotelian ethics encompass everything modern thinkers associate with subjective happiness: self-realisation, finding a meaning, and the flow of creative involvement with life, or positive emotion.

This book presents Aristotles time-honoured ethics in contemporary language. It applies Aristotles lessons to several practical real-life challenges: decision-making, writing a job application, communicating in an interview, using Aristotles chart of Virtues and Vices to analyse your own character, resisting temptation, and choosing friends and partners.

Wherever you are in life, Aristotles ideas can make you happier. Few philosophers, mystics, psychologists, or sociologists have ever done much more than restate his fundamental perceptions. But he stated them first, better, more clearly, and in a more holistic way than anyone subsequently. Each part of his prescription for being happy relates to a different phase of human life, but also intersects with all the others.