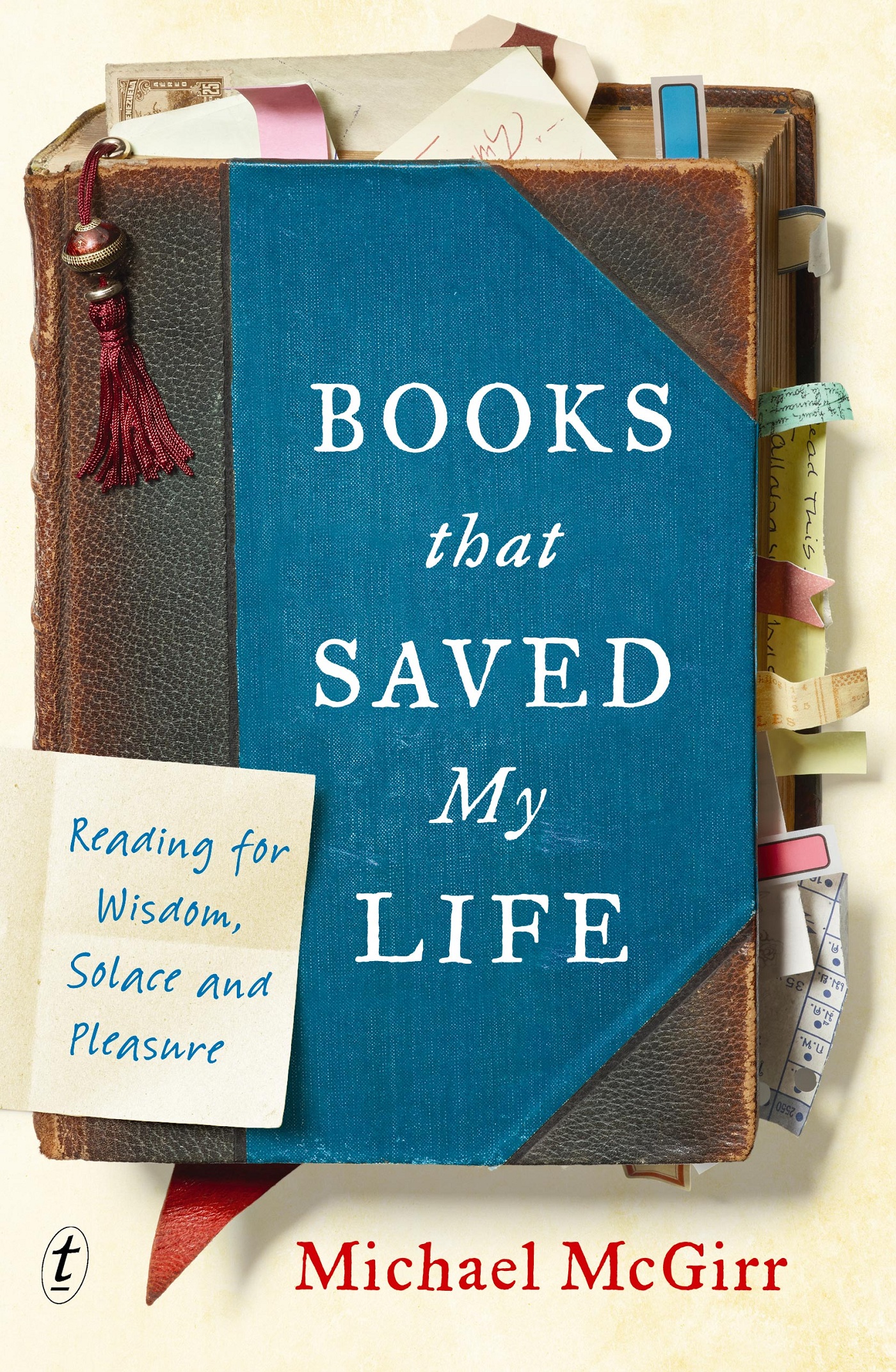

Here is a book about the sheer joy of living, exploring forty texts that can enrich us in all manner of ways. Some are recent, such as Harry Potter; some ancient, such as Homer and Lao Tzu. There are memoirs (Nelson Mandela), poetry (Les Murray) and many of the worlds great novels, from George Eliots Middlemarch to Toni Morrisons Beloved. This book uses them to muse upon life in all its glorious complexity.

Our guide, in entertaining short accounts of personal encounters with these works, is Michael McGirr: schoolteacher and father and lifelong lover of literature. His humour and insight shine through in essays that connect the texts he has selected with each other, and connect us to them.

This is the ideal companion for every keen reader and it may just inspire someone you know to become one, too. Never prescriptive, and often very funny, the book is an invitation to reflect on the extraordinary gift of reading. It is a gift that is taking me a lifetime to unwrap, McGirr writes. The excitement has never worn off.

For Chris Straford, 19612017

With love and gratitude

I say more: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces

Gerard Manley Hopkins

CONTENTS

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things

Gerard Manley Hopkins

At the school where I work, we run a special program in the depths of winter, immediately after the midyear examinations. We take our sixteen-year-old students to parts of the city they seldom visit, in order to ask them to think about justice in the broader community. Most of the students take their exams seriously and so, for quite a while, they will have been focussed on screens or desks about eighteen inches in front of their noses. It is time for them to look up and remind themselves that the world is a large and complex place, and our personal ambitions are only grains of sand on a vast beach.

I have been a teacher since Plato founded the academy and, in that time, have seen trends in education come and go, come again and go again. With each passing year, I am more convinced that the most important things that happen in a school are beyond easy measurement. We can be caught in a whirlwind of calibration, statistics, graphs, scores and results; and, like any gale, these are forces that play havoc with your hair, if not your whole head. I understand why we have assessment and standards, and I understand how clear standards often help less-gifted students. Nevertheless, a good deal of educational fine print is an expression of a deep anxiety, the rot that can drain schools of life. You have to remember there is always a person under all these numbers. Human beings do not always grow according to the progression points assigned by a bureaucracy. Nor do they ever grow without taking risks.

On one of our retreat days, I was with a delightful group of young men in inner Melbourne. Our program was simple. We began by sitting out in the cold for half an hour or so as the rest of the world was scuttling off to work, just watching the passing parade. Then we visited a centre that helps homeless young people. Our guide took us to several places where people sleep rough, and the students were surprised by how ingeniously they manage to hide themselves in a crowded city. Later in the day we visited a court to see justice in action for people at the raw end of lifes deal.

One of our boys was Antonio. He was a great kid, otherwise I would hardly be bothered telling this story. His instincts were a little authoritarian but not unkind. He did not believe in safe-injecting spaces for the drug-dependent because, in his view, such facilities might encourage an unhealthy lifestyle. He wanted rapid solutions to youth homelessness. While he was one of those for whom the word crime is never far from its shadow, punishment, he believed, like Plato, that education could solve many of the worlds problems. He could articulate his point of view with clarity and tact, if not always a lot of empathy.

For lunch that day, we went to a vegetarian caf run by the Hare Krishnas. It was a far cry from the Golden Arches, butsurprise, surprisethe students enjoyed the bean curry and mango pudding. Our conversation started with the encounters of the morning and soon moved to the recent examinations, because the boys had received their results for English. Antonio had one of the best grades in the year level of 260 students. He was understandably pleased with himself.

Well, I said, you clearly must have enjoyed To Kill a Mockingbird.

The students had been required to read the famous book by Harper Lee (19262016), the only one she published in her lifetime. It has been a staple of high-school English since it was published in 1960, the year before I was born.

Oh no, he said.

What do you mean by Oh no?

Well, sir, I never read it.

I was flabbergasted. What do you mean, you never read it?

Well, sir, I started and got a few pages into it but decided I didnt like it and I didnt have time to waste on reading all those pages, so I just used the plot summary on Google.

~

This is a book about why Antonio should have readreally readTo Kill a Mockingbird. It is a book about why he should still go ahead and read it, now that he is never going to face it in an examination but is only going to face the rest of his life, which I hope will be wonderful.

It is possible that, had he read the novel, his result in the examination might not have been as good. He might not have been able to make his argument with as much clarity and precision. His certainties might have been muddied by the novel itself. But clarity and precision are not the primary purposes of reading. To Kill a Mockingbird, like any great work of literature, has far more nuance than any plot summary, however detailed, can hope to provide. The thing that literature offers, not unlike our retreat day, is an experience of a broader world, one we can learn from but not control. Literature is, as my friend the poet Peter Steele (see ) used to say, an engagement with the imagination of another human being. Reading is among the few communal activities that you do on your own.

Like programs of community service, literature has a significant role in helping people to develop empathy and compassion. These are not measurable commodities, but society is aching for lack of them. I teach in a world that is starving in spite of its own excess. Literature can feed people who are being left hungry by a culture that is all package and little substance. It is one of the luxuries we cant do without.

Deep in To Kill a Mockingbird, there is a description of Mrs Henry Lafayette Dubose, an intimidating pillar of the white Southern town where this drama of race relations plays out. Mrs Dubose is addicted to the morphine she uses to control pain. With the realisation of this uncomfortable truth, an imaginary border between respectability and its opposite comes tumbling down. Mrs Duboses house is what you might call a safe-injecting space. There are a number of descriptions of her cold saliva, glistening around her mouth like ice.