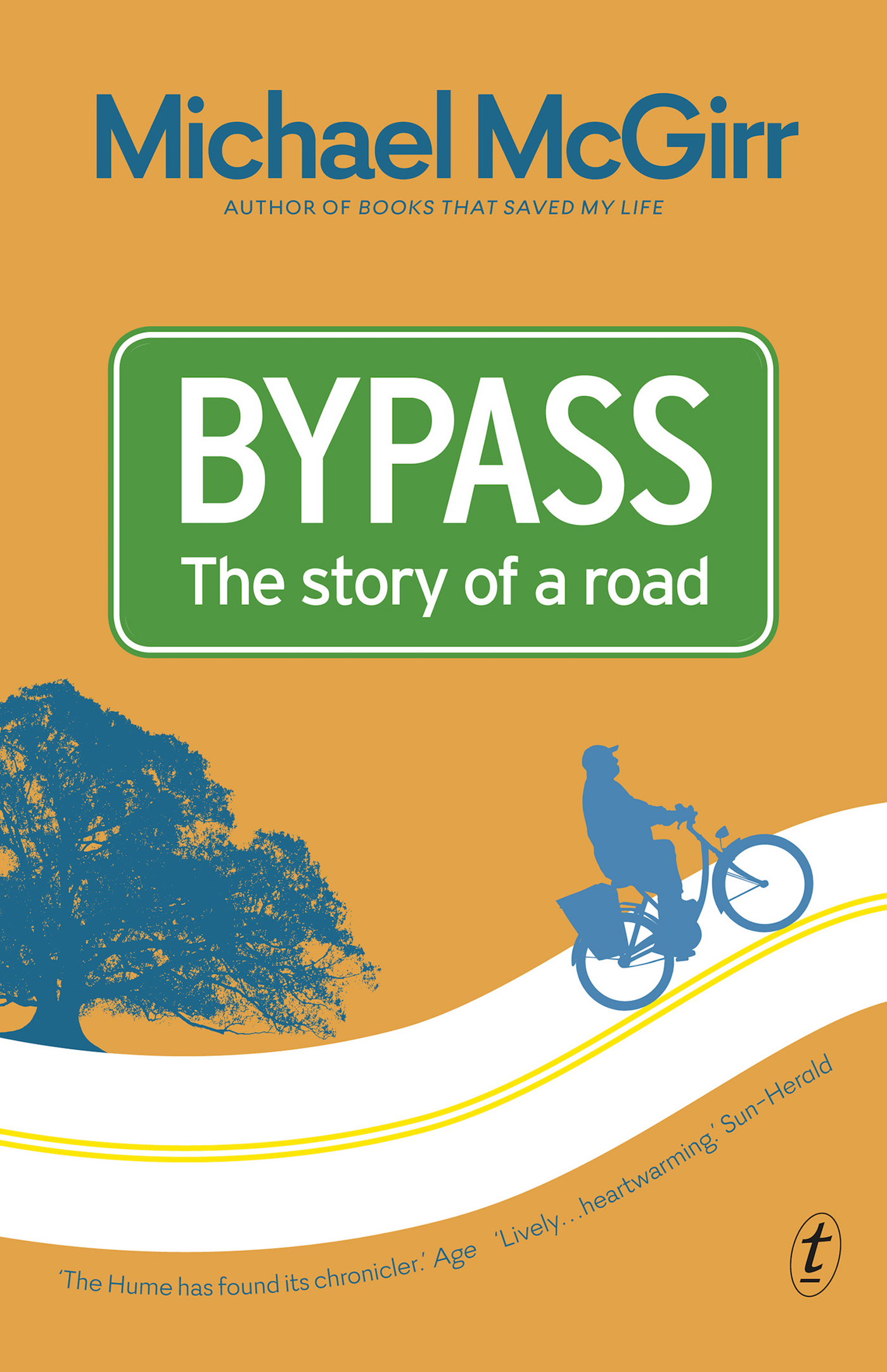

Forty and flabby, Michael McGirr hits the Hume Highway on a cheap bicycle. Having stopped working as a Jesuit priest, he is on a quest to find heaven knows what. Along the way, he is joined by Jenny.

Bypass is the story of Australias main street, the much-unloved highway between Sydney and Melbourne. The Hume has plenty of tales to tellof bushrangers and bus drivers, publicans and poets, runners and refugeesand McGirr discovers he has one to add to the swag. The road is a source of wisdom and comedy, and maybe even a fine romance.

One of the most popular books by the author of Things You Get for Free and Books that Saved My Life, Bypass is both a personal memoir and an unconventional biography of the road most travelled. This edition includes Passing By, a new afterword bringing the story up to date.

For Jenny

Give a man a road and he has a library.

MARY GILMORE, HOUND OF THE ROAD

Sancho answered, Theres no road so smooth that it aint got a few potholes.

CERVANTES, DON QUIXOTE

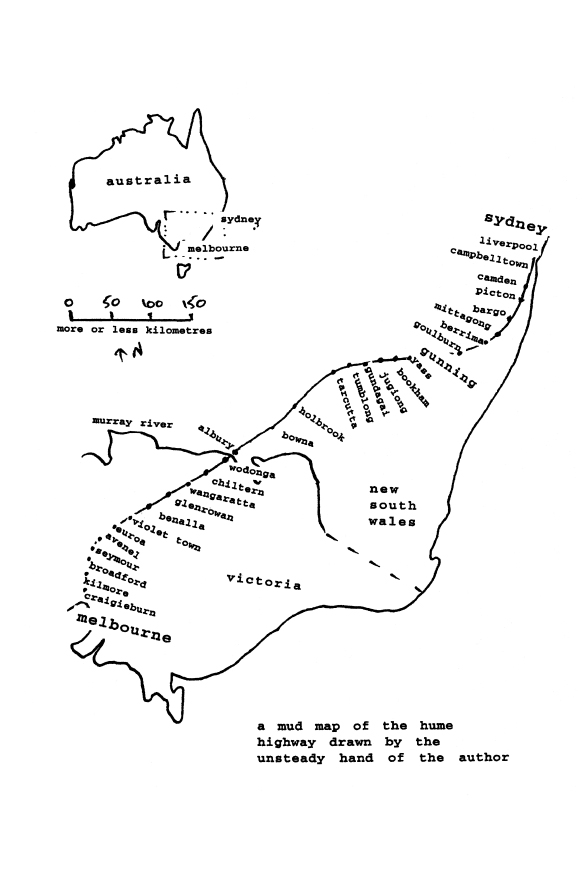

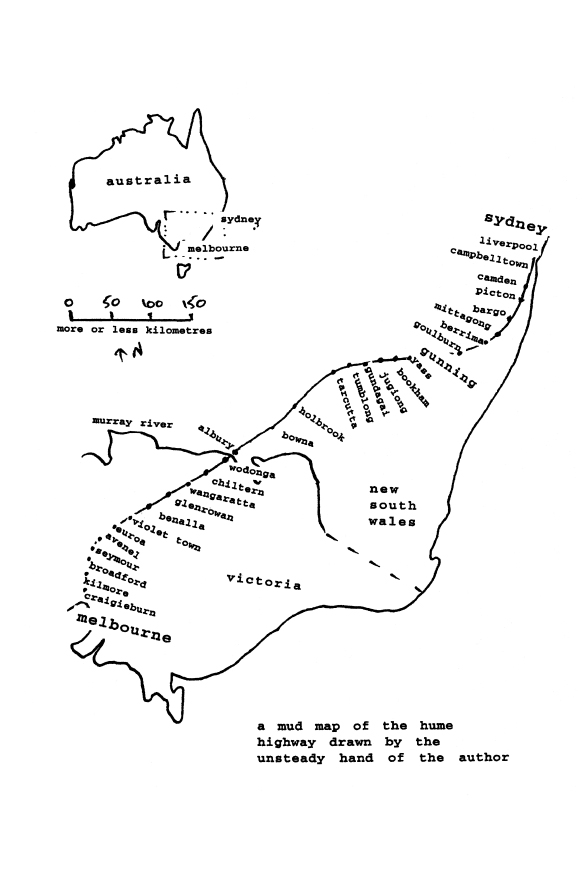

The Hume Highway has been known as both the Great South Road and the North-Eastern Highway. It is has been both Sydney Road and Melbourne Road. In various times and places it has been George Street, Broadway, Liverpool Road, Camden Valley Way, Remembrance Drive, Argyle Street, Auburn Street, Hume Street, Cullerin Road, Yass Street, Yass Valley Way, Comur Street, Sheridan Street, Dean Street, Young Street, Wagga Road, Wodonga Place, Conness Street, Tone Road, Murphy Street, Parfet Road, Ryley Street, Bridge Street and Royal Parade. Parts of it are the Old Hume Highway and parts of it are the Hume Freeway. All of these names are used in this book and others as well. Often it is just called the road.

Nobody had heard of Cliff Young. In late 1982, his application to run in a foot race from Sydney to Melbourne turned up on Martin Noonans desk. Noonan thought it was some kind of joke. Young was sixty-one years of age. He came from the western districts of Victoria. He was a potato farmer and still lived at home with his mother, Mary. She was eighty-nine and kept fit by cutting wood.

Noonan was helping to organise an event for elite athletes. He was the state marketing manager for Westfield, an empire of shopping centres which made a fortune by providing places where people could be bored in comfort. Westfield was already contributing to the fitness of the nation by getting its citizens to push trolley loads of consumer goods from the checkout to the carpark. They got an extra workout when the wheels of the trolley went in four different directions at the same time.

Noonan, a dedicated runner himself, wondered if Westfield could sponsor something in Melbourne a bit like Sydneys City to Surf, an annual race which attracts over 50,000 entrants. Melbourne used to call it the City to Sewer because the finishing point, Bondi Beach, had trouble in those days with effluent outflow. For various reasons, the City to Surf idea was not going to work in Melbourne. Melbourne had a city but no surf. A similar distance to the Sydney event would have taken runners from the city to the northern suburb of Fawkner, best known for its memorial park, but the City to Cemetery concept was hard to sell. This was despite the fact the City to Surf often kills at least one of its entrants, usually somebody well on in years who has decided that by keeping fit they will live forever. The plan went on the shelf.

A year later, Noonan heard that fellow runner John Toleman wanted to stage an event to showcase the abilities of two athletes he admired, George Perdon and Tony Rafferty. Perdon was fifty-eight and Rafferty was forty-four. They had both run from Perth to Sydney, a distance of over 4,000 kilometres. They were rivals. Noonan got in touch and said that Westfield was interested in employing Toleman to direct an event which would be open to as wide a field as possible. Westfield would put up a prize of $10,000 and meet the running costs for a race between Australias two largest cities. It became a race between Australias two largest shopping centres, Westfield Parramatta, in Sydneys western suburbs, and Westfield Doncaster, in Melbournes east. Before long, twelve competitors had come forward. Cliff Young was among them.

Young was part of a movement. In the early eighties, the whole world was running long distances. The craze was accompanied by fad diets, an obsession with shoes and a library of literature which explored the dark territory between psychology and sweat. There was a bestseller called The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. The attraction of running, many said, was the isolation. So they joined fun runs in which tens of thousands jostled each other in the quest for solitude. Eventually the fad died when runners discovered that their knees were unable to read all those books.

Noonan, a serious runner, was on the Pritikin diet. Cliff Young wasnt. He told Noonan that he needed oil in his diet to keep his bones lubricated. He also said that he did most of his training running round the paddocks in gumboots.

Young had been running seriously for only three years. Before that, hed tried hang-gliding but found it was too dangerous. He had played football for his local team, Colac, until he was forty and was disappointed to have been retired on account of his age. When his application arrived, Noonan thought he better take Cliff out for a bit of a run to make sure he was up to the task.

Not only was Cliff in remarkable physical condition but he was a natural wit. He had an answer to everything. He said that where he came from it rained for nine months of the year. Then the winter set in.

A press release went out saying that one of the competitors trained in gumboots. From that moment, Young had a toehold in the public imagination. He was running against technology. At the media launch of the event, a journalist asked Cliff why he wasnt wearing gumboots today. Cliff said that hed been given a pair of new-fangled fancy runners. They were so good, he said, that it took him 200 metres to slow down and stop.

On 27 April 1983, the field set off at a cracking pace along the road from Sydney to Melbourne. They did the first 42 kilometres, the length of a marathon, in less than three hours. Cliff took a wrong turn. He said later that he was lucky he didnt run to Darwin by mistake. Another competitor pointed him in the right direction.

DONT JUST DO SOMETHING. SIT THERE.

Bumper sticker, Hume Highway

You dont come to a small town to hide. There are cities for that. If you want to move to a town like Gunning the best place to start is where most people come to rest: the local cemetery. The sign out on the freeway says the population of Gunning is 1,000 but thats an exaggeration. Until 1993, when the town was bypassed, its main street was part of the road between Australias two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne. Suddenly it became the main road between the post office and the pub. Towns such as Gunning, where I live, were offered signage on the new freeway to let travellers know they still existed. The bigger the town, the bigger the sign, so rather than quietly disappear, Gunning fibbed. The sign on the way into town, which says that the population is 530, is more honest. Once upon a time, somebody announced a new arrival by changing 530 to 531, an item of graffiti which has never been removed. People like it. It suggests that the place is growing.

Next page