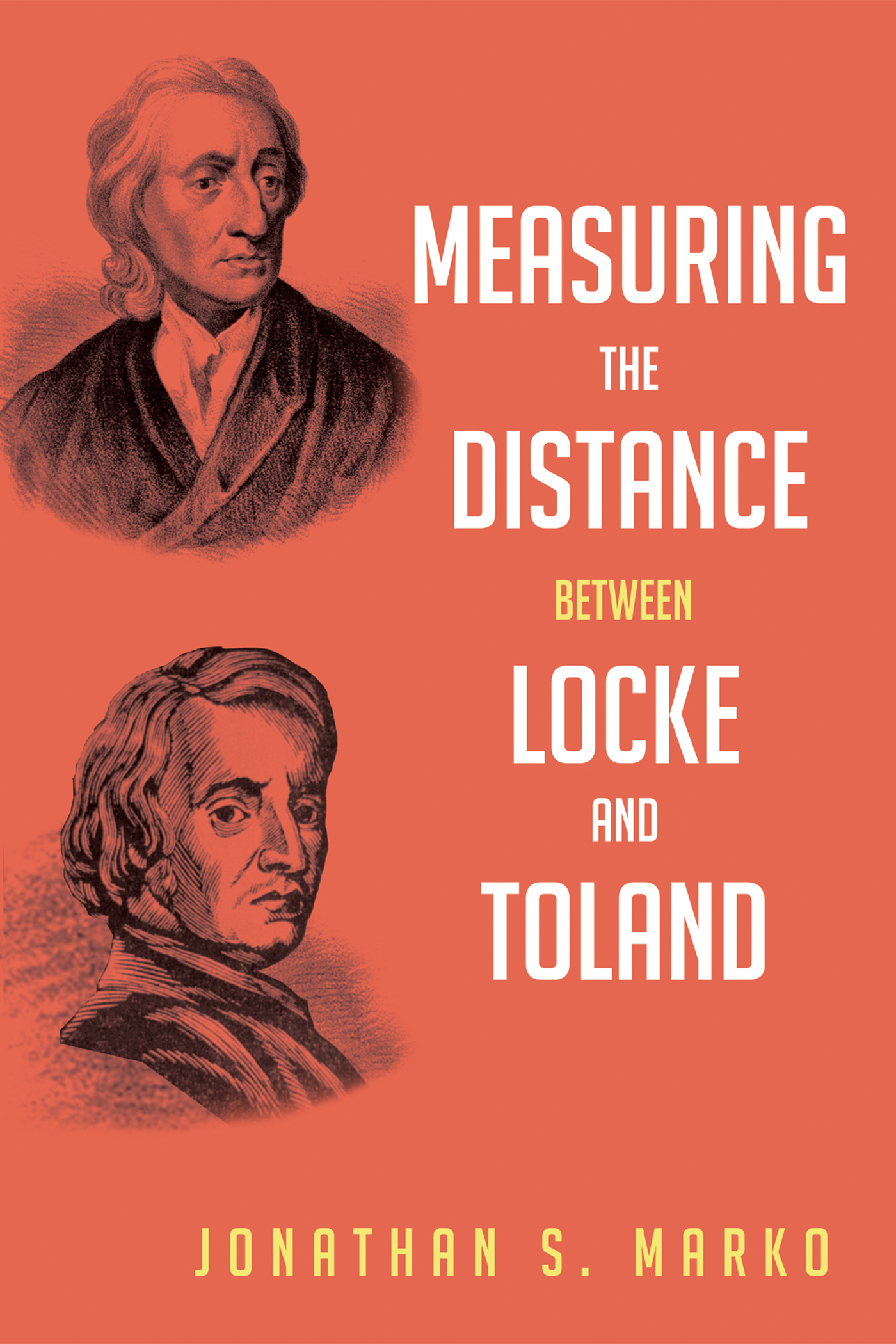

Measuring the Distance between Locke and Toland

Reason, Revelation, and Rejection during the Locke-Stillingfleet Debate

Jonathan S. Marko

Introduction

A Reasonable Narrative from Mysterious Premises

A ny history of philosophy that covers the rise of deism or the rise of natural religion in England will inevitably juxtapose John Locke ( 1632 1704 ) and John Toland ( 1670 1722 ). John Locke was perhaps the great mind of his time and his magnum opus, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding ( Essay ), still piques the interest and draws the scrutiny of historians, philosophers, and theologians alike. Because Locke looms so large and draws the focus of so many, those who became attached to him in one way or another were effectively saved from the indefinite limbo of historical obscurity. This is the case with John Toland. His work Christianity Not Mysterious ( CNM ) is best known for its use of Lockean principles with a few modifications in a scathing critique of the then-current religious establishments. While Locke cultivated religious mysteries with his epistemological ploughshare, Toland beats it into a sword and lops away the mysterious fruits of revelation growing above the soil of reason. Thus Toland is the first of a generation of so-called deists who use and modify Lockes epistemology to promulgate natural religion and critique Christianity, or so the story goes.

It is not just the philosophical differences between Locke and Toland that make an exploration of Toland enticing, but also the personal characteristics attributed to him in the histories of philosophy. In these accounts we are often introduced to Locke the Reputable and Toland the Disreputable. Whatever other adjectives one might apply to Locke, such as heretical or orthodox, he is consistently portrayed as brilliant and honest. He is the venerable gentleman at Oates earnestly trying to make sense of religion and reason come what may. Portrayals of Toland, while various, are rarely complimentary. For instance, Leslie Stephen introduces Toland with the following description:

From his earliest days Toland was a mere waif and stray, hanging loose upon society, retiring at intervals into the profoundest recesses of Grub Street, emerging again by fits to candalize the whole respectable world, and then once more sinking back into tenfold obscurity. His career is made more pathetic by his incessant efforts to clutch at various supports, which always gave way as he grasped at them.

And subsequently, where Stephen discusses CNM as being the root cause of the embittered debate between Locke and Edward Stillingfleet ( 1635 ), he calculates, we may fancy Toland chuckling with all the vanity of gratified mischief.

With such descriptions of Toland circulating in important historical works such as Stephens, it is easy to imagine in CNM the significant and cleverly subtle epistemological deviations from the Essay that are alluded to in Toland scholarship. The converse is true as well. But before adopting the contours of this narrative a few basic questions are in order. How, exactly, do Lockes and Tolands epistemologies differ? Tiresome quick descriptions, such as that Locke accepts religious mysteries and Toland does not, simply lack definitive boundaries and create more questions. Locke can be a large, quick, and elusive quarry. And if Toland is tethered to him, Locke must be caught before trying to measure the distance between the two.

Overall Argument

This book will compare the epistemologies of John Locke and John Toland based upon Lockes Essay and Tolands CNM and their related works. In so doing, it will also evaluate Bishop Edward Stillingfleets comparison of the two works. This book contends that the differences between Locke and Toland with respect to their epistemologies are not based upon or evidenced by their respective categorizations of propositions, but rather on Tolands attempt at working out the implications of Lockes epistemological principles in conjunction with Tolands interpretations of certain biblical passages and certain theological preferences and presuppositions. Had Locke ordered propositions according to his preferred consideration of reason, his categorization of propositions would be the same ascribed to Toland. The resultant, substantial differences between Locke and Toland in their understandings of epistemology are connected with Tolands definite or likely rejections of theological and philosophical positions that Locke does not dismiss: post-New Testament original revelation and miracles, non-materialism of the soul, and prior-to-the-close-of-the-New-Testament divine revelation requiring a supernaturally bestowed faculty and private miracles for believers.

The State of the Problem

John Toland penned numerous books on a variety of topics in his nearly three decades of writing, but the book that brought him the most notoriety was his very first, CNM .

Despite the glaring mistakes Locke points out in Stillingfleets understanding of the notions of ideas, certainty, and knowledge found in the Essay and Tolands CNM , Toland is still to this day portrayed somewhat as Stillingfleet paints him. While originally portrayed by Stillingfleet as having brought the Essays foundational principles to their true unorthodox end, namely that certainty can only be had by and reasoning could only be done with clear and distinct ideas, Toland is now portrayed as having largely borrowed from the Essay and having adapted it to his own heretical ends. This altered picture stands because most are skeptical of or deny the accuracy of Stillingfleets reading of Locke and the Essay in light of Lockes defense, but for some reason assume that the bishops reading of Tolands CNM is correct.

Scholarly assessments of Toland tend to abound with a few major, intertwined problems related to this prevailing view that Stillingfleet correctly read CNM and that Toland did greatly diverge from Locke despite the fact that both built on similar foundations. Supporting or resulting from this view are three common assertions often made regarding the juxtaposition of Locke and Toland: ) Toland appropriates the foundational principles of Lockes Essay to a significant degree, ) Locke accepts above reason propositions, while Toland does not, and ) Locke accepts divine revelation and Toland rejects, or essentially rejects, divine revelation by subordinating it to reason.

These three assertions, which are related to the prevailing view of CNM , are teeming with problems. Assertion onethat Toland appropriates the foundational principles of Lockes Essay to a significant degree or that Toland is dependent on Lockeis vague but widely held.

Assertion twothat Locke accepts above reason propositions, while Toland does notis the most widely known. There is seemingly clear textual evidence that Locke accepts above reason things and Toland rejects them. On the one hand, Locke discusses above reason propositions in multiple places (IV.xvii.; IV.xviii.) and affirms them. On the other hand, the full title of Tolands CNM is Christianity Not Mysterious: or, A Treatise Shewing, That There is Nothing in the Gospel Contrary to Reason, Nor Above It: and That No Christian Doctrine Can Be Properly Calld a Mystery . In fact, it seems as though this textual evidence clearly supports the prevailing view that Toland, the disciple, attacked his master. But, due to the lack of specificity of assertion one, an imposing assumption actually undergirds assertion two. The assumption is that Locke and Toland are operating with the same notion of reason in Lockes acceptance of things that are above reason and Tolands rejection of things that are above reason. Yet, as will be demonstrated, Locke operates with two rather distinct understandings of reason in the chapters of the Essay that are most often juxtaposed with CNM . What is more, no one has attempted an in depth explanation of Tolands understanding of reason, which is needed to be able to compare it to Lockes. To operate as if it is the same as Lockes is not only presumptuous but problematic since Lockes understanding of reason is one of the most contested topics in Locke scholarship. In addition, in Locke scholarship there is general confusion precisely as to what above reason propositions are.