Daoist Immortal Three Peaks Zhang Series

Tai Ji Quan Treatise

( , Tai Ji Quan Lun)

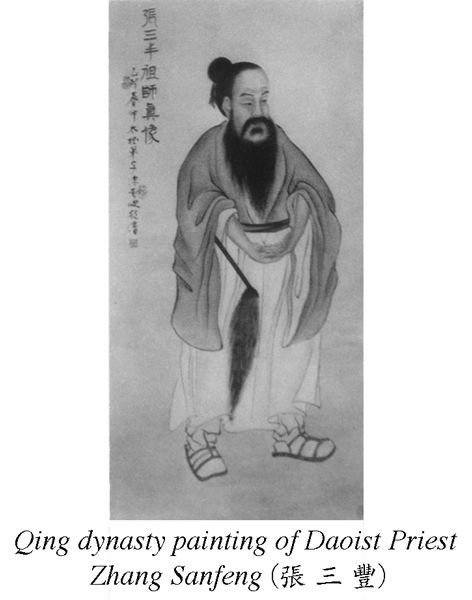

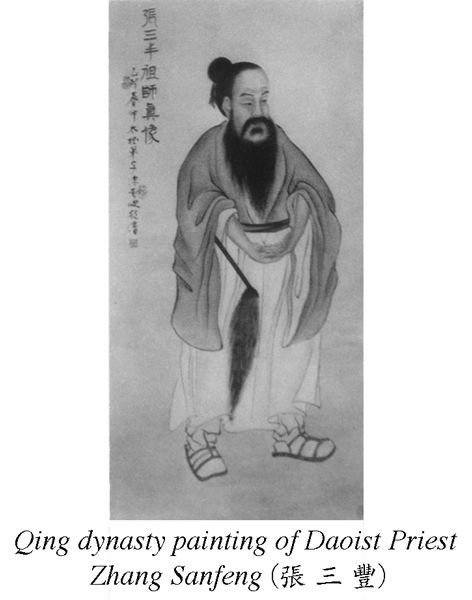

Attributed to the Song Dynasty Daoist Priest Zhang Sanfeng

Translation and Commentary by Stuart Alve Olson

Contents

Acknowledgments

To my teacher Master T.T. Liang, without whom this book or any of the others I have written or translated would never have been possible.

To Patrick Gross, longtime student and cofounder of Valley Spirit Arts, for editing and formatting this material, as well as for his help with my many other projects.

To my wife, Lily Shank, for her thoughtful review and suggestions on this work.

To all my students, whose inspiration and dedication over the years have resulted in my wanting to write this book for their reference and practice of Taijiquan.

Tai Ji Quan Master T.T. Liang

(1900 to 2002)

Photograph by Richard Peterson, Portland, Oregon, 1996.

Preface

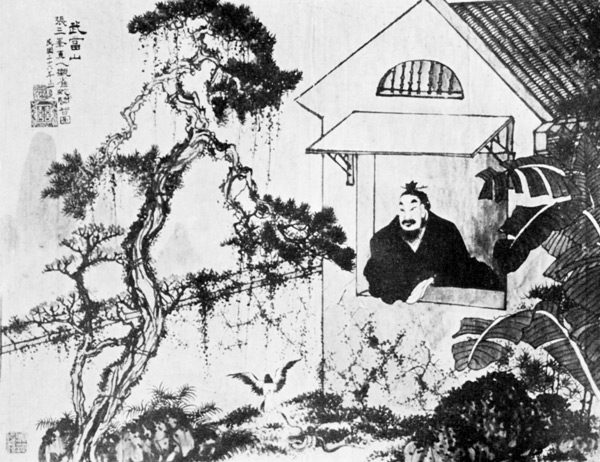

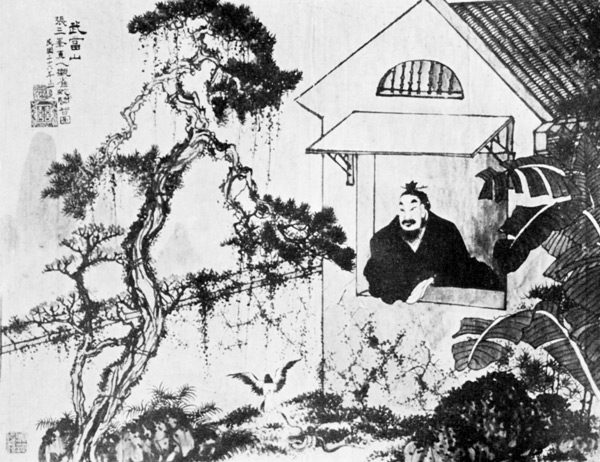

Zhang Sanfeng watching a bird attack a snake.

Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan), at its core, is not a martial art, at least not in the sense of what is commonly thought of as martial art. Taijiquan is not really even a system of self-defense. Rather, its a system of defense against the self, as the main premise of practical application has more to do with a disciplined and trained response so you will not make the errors and defects that cause injury to your self. If you were attacked, for example, Taijiquan teaches you to yield and use an attackers force against them, instead of relying on force, strength, speed, or techniques to overcome the opponent.

In nature, when snow falls upon a pine trees branch and the weight of the snow becomes extreme, the branch bends, the snow falls away, and the branch naturally snaps back into place. This is the same natural reactionary energy used within Taijiquan. Therefore, it is incorrect to say that Taijiquan is a martial art full of techniques relying on speed and strength. Even the story of how Zhang Sanfeng created Taijiquan demonstrates this aspect of using natural reactionary energy by relating how he had observed a snake defend itself against a birds attack. Briefly, when the bird attacked the snakes head, the snakes tail would respond. When the bird attacked the tail, the snakes head responded. If the bird then went for the snakes body, both the snakes head and tail reacted.

When reading this book, keep this concept of using natural reactionary energy firmly rooted in your mind, rather than the practice of using external muscular force that is set forth in descriptions of many oth er martial art systems.

Taijiquan is based entirely on natural simplicity, which is so simple that it protects itself from discovery by most practitioners, especially those who attempt to view Taijiquan as a martial art.

The full scope of Taijiquan practice contains the following four benefits and goals:

1. Health and Longevity.

2. Defense Against the Self.

3. Mental Accomplishment and Wisdom.

4. Immortality and Internal Alchemy.

Although Taijiquan encompasses these four areas of practice and accomplishment, which sound difficult to achieve, they are all natural responses rooted in simplicity. Just as Zhang Sanfeng discovered long ago while seated in his meditation hut watching a bird attack a snake, the secret of the art lies in responding to what life throws at you in a natural, yielding, and simple manner. If you can keep this in mind and apply it to your life and practice, you can go far in acquiring the skills and benefits of Taijiquan.

Introduction

This work on Zhang Sanfeng and the Tai Ji Quan Treatise attributed to him provides a fundamental basis on which to study and practice Taijiquan. So many modern-day practitioners have no historical knowledge of the origins of Taijiquan nor of its great masters. The primary figure in the formation of Taijiquan is directly laid at the feet of the great immortal Daoist priest Zhang Sanfeng (Three Peaks Zhang). This work provides an in-depth biographical sketch of this elusive and shadowy figure, whose life spanned three dynastiesthe Song, Yuan, and Ming. Despite the difficulty in proving the existence of Zhang and his invention of Taijiquan, it is important for Taijiquan practitioners to have knowledge of his person and life, so they may gain a broader understanding of Taijiquan and its connection to Daoist philosophy and internal alchemy ( , neidan). No matter the initial purpose or reason why people take up Taijiquan practice, they knowingly or unknowingly will delve into these two esoteric worlds.

Taijiquan is presently being taught throughout Western culture without any depth of understanding of the underlying principles or knowledge of the traditional writingsand this material, hopefully, elucidates the necessary need for traditional theory. Not studying Taijiquan classical literature only serves to denigrate the art, so it is my sincere hope that this material helps fill the gap between practice and theory.

Four primary reasons and functions exist for the practice of Taijiquan:

1. Health: Taijiquan is the ultimate Qigong exercise as it increases blood circulation, strengthens central equilibrium, produces a deep relaxation of mind and body, and revitalizes the spirit.

2. Self-Defense: Taijiquan is not so much a means of self-defense as it is a defense against the self. Meaning, from our own faults of lacking intuition, inability to move our bodies as one unit with the breath, poor sense of central equilibrium, and absence of intrinsic energy skills, we make the mistakes that lead to injury and defeat.

3. Wisdom: An inherent mental accomplishment of wisdom comes with Taijiquan practice and study. Taijiquan is Daoist philosophy in motion and the more we understand its fundamental principles and philosophies, the more we can integrate them into our daily life. Taijiquan is not just about movement; it is more about living in accord with the world around us.

4. Immortality: Taijiquan is internal alchemy, the development of jing (, regenerative energy), qi (, vital-life energy), and shen (, spirit). The practice of Taijiquan leads to longevity, and longevity leads to the strengthening of our spirit. When we have fully awakened our spirit, we can become immortal, at least in the Daoist sense of passing from this world fully conscious.

As my teacher remarked, No Taijiquan teacher is worth their salt unless they can explain and interpret the meaning of these four functions in every verse of the Taijiquan classical literature. This means that to master Taijiquan, a practitioner must not only thoroughly understand the importance of each of these four functions, but also practice according to the goals of each of them. It is not enough to just practice Taijiquan for health, as the skills and goals of self-defense, wisdom, and immortality are equally paramount to the mastery of this art of self-cultivation.

The Tai Ji Quan Treatise is the foremost text of all Taijiquan literature. It is one of three main texts, the other two being The Mental Elucidation of the Thirteen Kinetic Operations ( , Shi San Shi Xing Gong Xin)

Next page