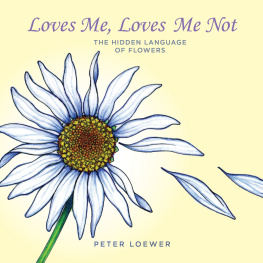

Copyright 2006, 2018 by Peter Loewer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

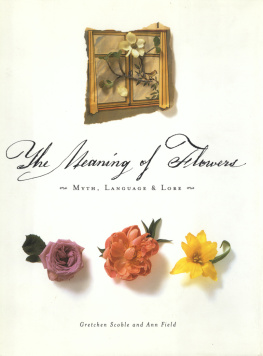

Cover design by Mona Lin

Cover illustration by Peter Loewer

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2783-0

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2786-1

Printed in China

To Jean, as always, for always being there!

Introduction

I suspect that even when men and women first walked upon the earth, a gentleman would offer a lady a flower. This probably happened most on those days when the weather was fine, few volcanoes were erupting, and there was plenty of food in the cave.

When we reached the more civilized days of Greece, Rome, and Ancient Egypt, many of the wealthier citizens celebrated important occasions with the presentation of flowers to their lady (or man) friends. The rose was thought to be sacred to many of the Greek gods and was grown in gardens as well as in containers. The rose was not only a symbol of joy, it also symbolized secrecy and silence. Over the centuries, the culture of the rose changed, and today its the perfect emblem of love and romance.

The evolution of flowers as symbols required the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague, who accompanied her husband, the ambassador to Turkey, to his post in 1717. Her letters from the Turkish Embassy were published in 1763, shortly after her death. These letters, which made her famous, described all aspects of Turkish life, including the world of diplomacy, of trade, of the streets, of life in the seraglios, and all about the language of flowers.

Being an educated woman, she didnt approve of the reasons behind the floral codea little-known fact, except by some researchers and biographers. She knew that the language of flowers was developed because the women in the Ottoman Seraglio were basically illiterate and the only way they could secretly communicate was by using the floral code. Lady Montague described that code with scorn, but her opinion was soon lost and the language of flowers became the rage of England and Europe, reaching its peak in the Victorian era.

One reason the floral code became so popular was the number of common, rare, and decidedly exotic flowers that were featured in the flower stalls in England and much of Europe. During the heyday of the Victorians, finding a flower to match the code was among the easier things to accomplish.

Interestingly, it is said the Victorians were prudish people, but some researchers point out that a few of the books that defined the various floral codes were decidedly erotic in their entries and are very difficult to find today in the world of used books and rare editions.

The business of Victorian publishing was competitive, and when a new dictionary of flowers appeared, it often gave new definitions to many of the flowers featured in the book. So a user had to be sure that the recipient had the same book on his or her shelf that the sender used to make the bouquet.

My first introduction to the use of flowers as symbols of language came as the result of research gathered when writing The Evening Garden (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1993), a book revolving around the blossoms of the night. Then I found mention again in a book entitled Garden Facts and Fancies , by Alfred Carl Hottes (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1949), and over the years I collected whatever information I could find.

But history aside, the language of flowers is a delightful idea. In a world of cell phones and iPads, sending a simple bouquet to a beloved that tells a tale of love and affection is a great idea whose time has come again.

Amaryllis

SPLENDID BEAUTY; PRIDE

The original amaryllis was named after a Grecian beauty who appeared in a literary piece by the Roman poet Virgil (7019 BC). Described as a fair shepherdess, Amaryllis is serenaded by a handsome shepherd who is struck by her charmand wooing ensues. Amaryllis bulbs, originally from South Africa, were viewed as insignificant plants until they opened with blossoms of such flamboyant appeal that calling them splendid beauties has never been out of place. The disarming beauty of the flowers conveys a confidence that is the source of the second meaning, pride .

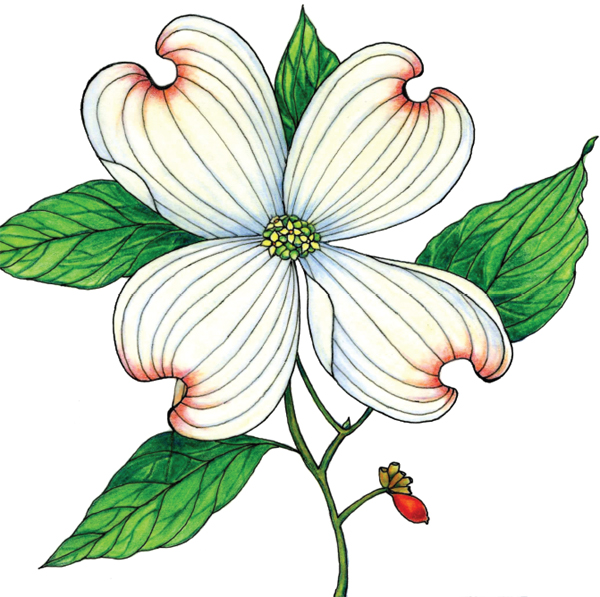

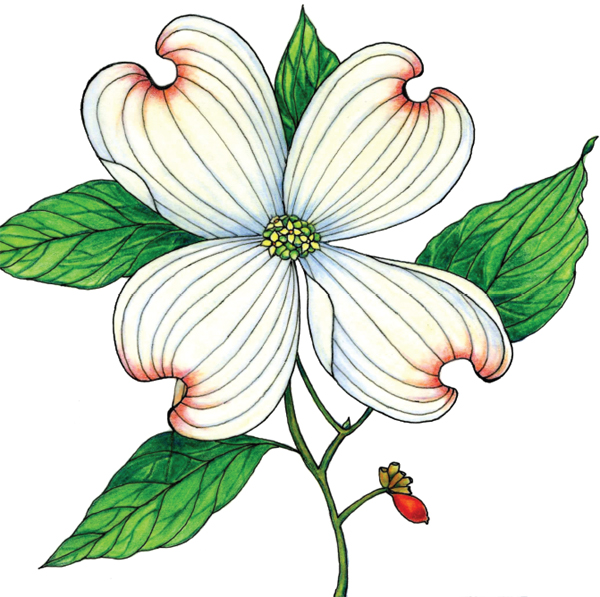

American Dogwood

DURABILITY; INDIFFERENCE

Like many other attractive American plant species, dogwoods were well known in England. The common name is actually said to be an old English term referring to the use of the bark to make a medicine for ailing dogs. Though the tree is small, the wood is very tough and was used to make tool handles, hence its reputation for durability . Indifference probably springs from the fact that the petals are not really petals at all, but merely greenless leaves that encirclebut are not part ofthe tiny four-petaled flowers at the center.

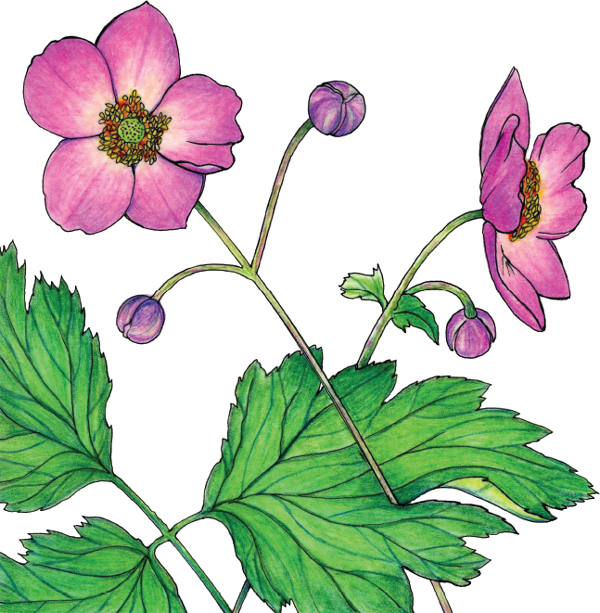

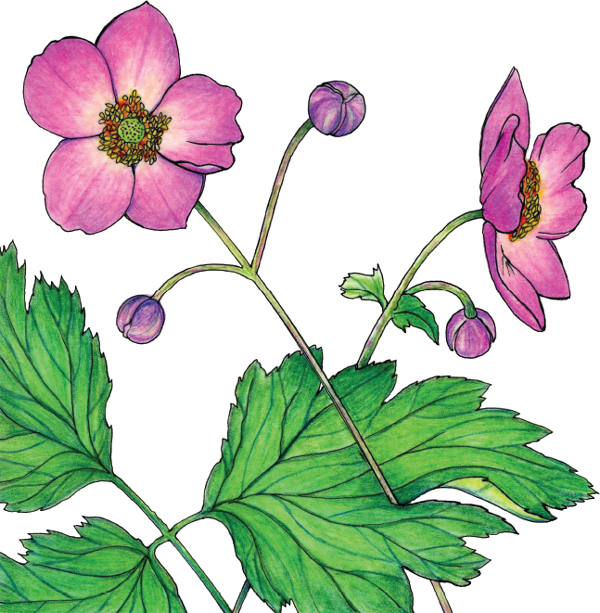

Anemone

FORSAKEN; TRANSITORY; ENDANGERED LOVE

Because the anemones blossoms were thought to open on windy days and theyre also short-lived, they have become a symbol of a transitory love that moves like a breath of wind. The original bloodred wildflowers were associated with the lovers Adonis and Aphrodite, and were said to spring from the tears of Aphrodite upon the passing of Adonis from the earthly scene. Todays anemones have a longer life before their petals begin to fall, but they are also symbolic of fading youth.

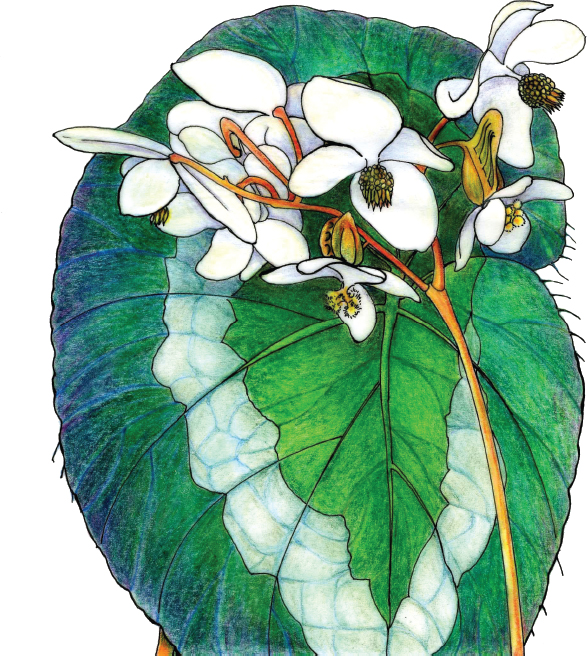

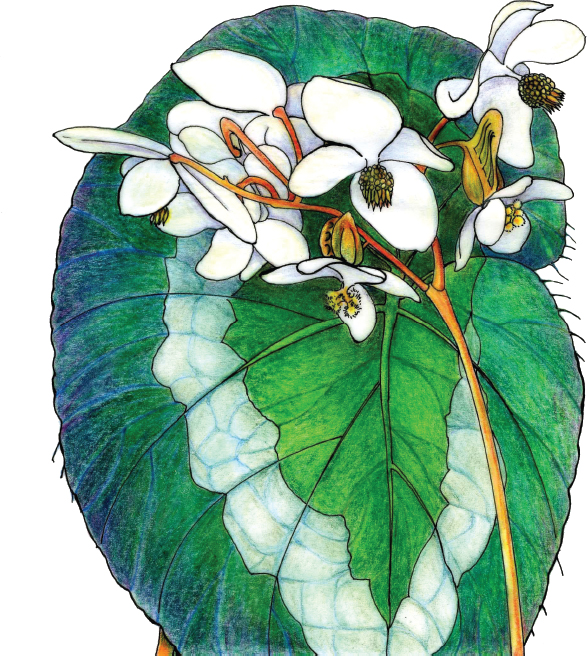

Begonia

BEWARE; BE CORDIAL; HAVING A FANCIFUL NATURE