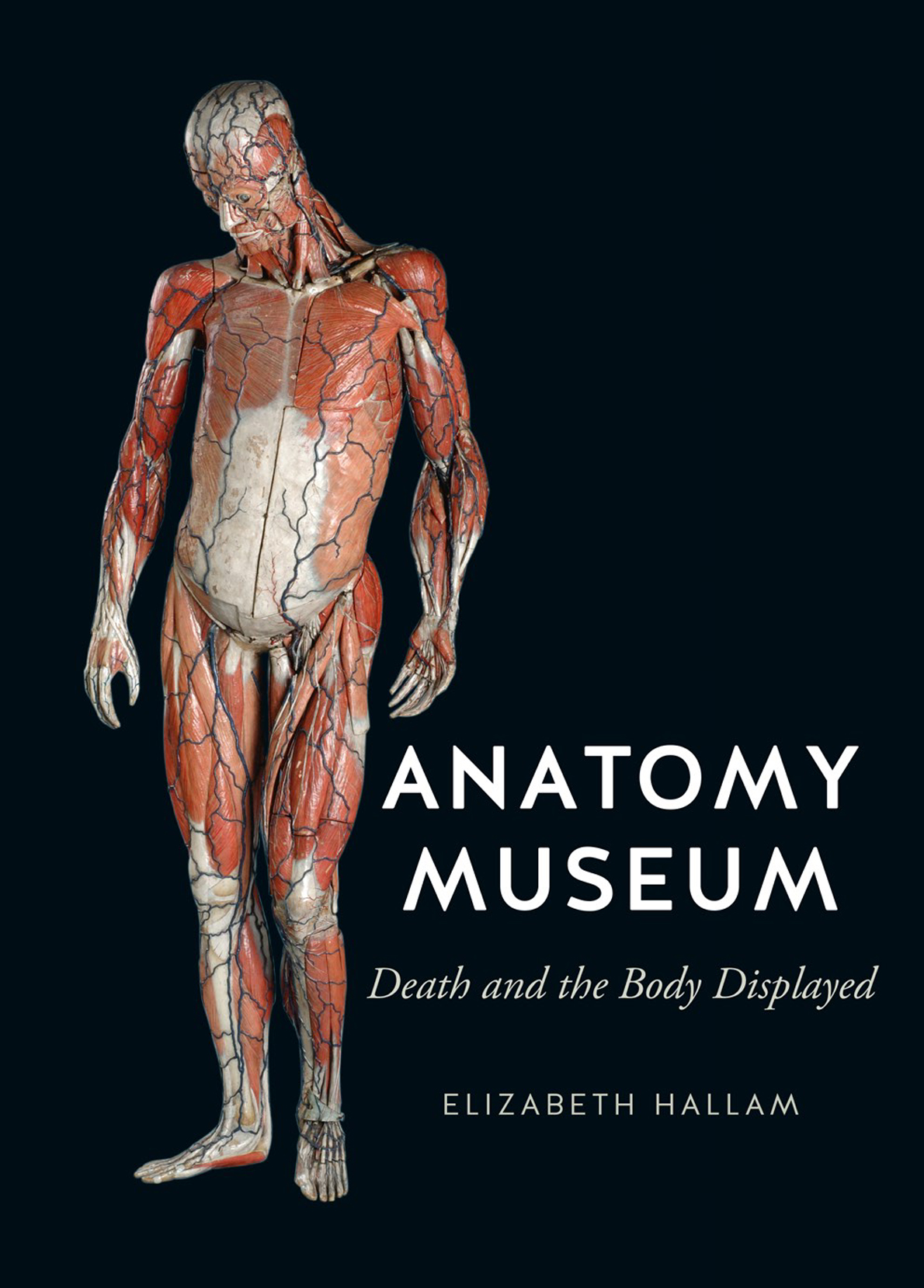

ANATOMY MUSEUM

ANATOMY MUSEUM

Death and the Body Displayed

Elizabeth Hallam

REAKTION BOOKS

To Ian, with love

And in memory of Beatrice Selina Hallam, 19081988

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448, Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright Elizabeth Hallam 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page References in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index Match the Printed Edition of this Book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780236049

CONTENTS

Introduction:

Articulating Anatomy

One Hand and Eye:

Dynamics of Tactile Display

Two Animations:

Relics, Rarities and Anatomical Preparations

Three Nerve Centre:

Museum Formation I

Four Skeletal Growth:

Museum Formation II

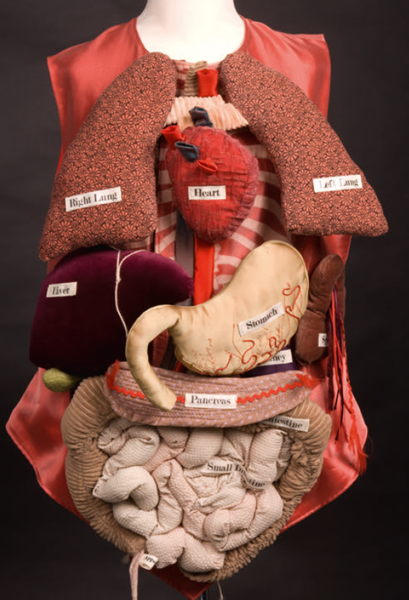

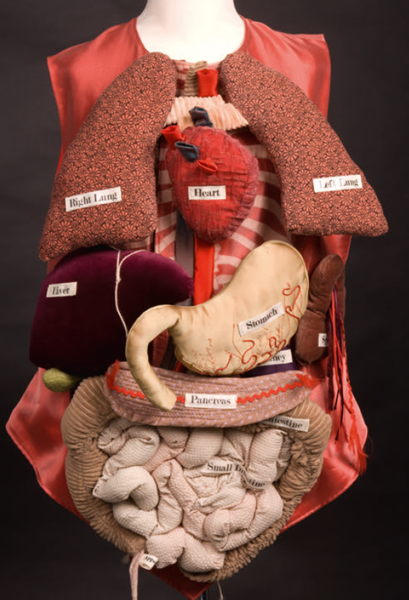

1 Jo Sheffield, textile anatomy: Organ Waistcoat, in the Hunterian Museum, Royal College of Surgeons of England, London, 2005.

INTRODUCTION: ARTICULATING ANATOMY

Almost immediately, he dreamt of a beating heart.

He dreamt it as active, warm, secret, the size of a closed fist, of garnet colour in the penumbra of a human body as yet without face or sex; with minute love he dreamt it, for fourteen lucid nights. Each night he perceived it with greater clarity. He did not touch it, but limited himself to witnessing it, observing it, perhaps correcting it with his eyes. He perceived it, lived it, from many distances and many angles.

Jorge Luis Borges, The Circular Ruins, in Labyrinths

This book is about human bodies: how they have been imagined, made visible and tangible in museums of anatomy and other related sites of display. It explores the collection and exhibition of bodies after death in historical and contemporary settings, asking how and why human remains have been acquired and preserved, and examining what these practices entail for the people involved in them. In Western societies deceased bodies have been significant in shaping perceptions of the human form and this study focuses on interactions that are sustained between the living and the dead in the pursuit of knowledge, especially knowledge of anatomy. Preserved human remains exhibited for visual contemplation and tactile examination have taken a diversity of forms, from saints relics and personal mementoes to works of art and anatomical specimens, or preparations, as they have also been termed.fragments, such as locks of hair, kept as emotive reminders of the deceased. Human bodies after death have been the focus of intensive anatomical investigation as well as ritualized action and memorialization all involving modes of display that hold the dead in proximity to the living.

Death is not always the end of social life for bodies. For bodies embark upon many trajectories as they are anatomized, observed, photographed and drawn, kept in storage or disposed of, in the dynamics of anatomical exposition.

Anatomy is a shifting, not fixed, field of knowledge that is constituted and communicated in practice within particular social and cultural contexts. How has the collection and display of bodies figured in this field of knowledge production and dissemination? How have anatomy museums been formed and transformed, and what kinds of cultural practices and social relationships are entailed? These museums operate within social networks of people that have included not only anatomists and their assistants, but artists, technicians, doctors, students, travellers, wealthy collectors, naturalists, taxidermists, model makers, anthropologists, architects, photographers and many other experts and non-specialists. Wide-ranging social connections, through which body parts have been transacted, are just as crucial in the development of anatomy museums as the intensive work on site to display and maintain those bodies.

Containing the remains of once-living persons and animals, collections in anatomy museums are both grown and made; they cut across the categories of the organic and the artefactual. The lives of those deceased and those alive become entwined in anatomical displays, just as those displays engage both their makers and their users/visitors. These engagements can be complex and potent, especially as the material objects comprising these anatomical displays are often difficult entities whose very substance has the capacity to provoke anxieties and whose form, matter and meanings are often unstable, ambiguous and changing.

2 Exploded human skull, c. 1920, by N. Rouppert (successor to Maison Tramond), Paris. |

|

Exploring bodies, of the anatomized and of those involved in anatomizing, this book attends to material and visual aspects of displays as well as the relations that enable, and are forged by, processes of body collecting ).

The adult skulls white bones are pristine with skin and muscle removed; there is no blood, no visible decay. Eyes and brain have long been separated from the skull, which was originally prepared for a particular purpose to show the bony components of the head without any messy matter to obscure them. Only neat lines of coloured, waxed fibres in the upper and lower jaw, standing for blood vessels and nerves, thread through this ossified structure. Bones in the skull have been carefully prized apart along suture lines, or serrated seams, and the fragments held together by a brass framework.

The anonymous skull, removed from the person within whose body it once lived, is stripped of the skin and facial features so closely associated with particular individuals and culturally valued as indicators of gender, age and ethnicity.

The exploded skull is marked with inscriptions, indicators of the meanings and associations it has accrued through its post-mortem life. The label N. Rouppert Paris refers to the commercial firm which preserved and sold it an hisorically well-reputed supplier of osteological specimens and maker of anatomical models. The year of its purchase, 1920, was written in black ink by Robert William Reid (18511939), professor of anatomy at Marischal College and curator of the Anatomy Museum at the time. The inscriptions register some of the social relations in which the skull has been entangled as it passed from a deceased person though a specialist business in Paris and on to Aberdeen for use in teaching anatomy. Such a route taken by a body part is just one among a multitude of movements, all varying according to historical period and place, involved in the formation of anatomy, pathology and other medical museums.

The skull has also entered the lives of students who have interacted with it during their medical training. According to Robert Douglas Lockhart (18941987), one of Reids successors as professor of anatomy, each human skull was like a jigsaw that required an eye for shape and position in order to understand it from an anatomical point of view. In this context, the exploded skull would have been studied through observation conducted within a disciplined, physically and imaginatively active learning process.