The human body is a wondrous structure and learning how it works is a constant source of amazement to the inquisitive mind. Not only does knowledge of the body and how it functions equip us with a wealth of fun facts with which to impress others, it is perhaps the best way to understand how our life choices affect our own physical well-being, helping us to make sense of who we are and what happens within us when things go wrong. Broadly-speaking, most structures in our body have a known purpose and exist to allow us to function to our maximum potential. There are organs without which we simply cannot live. Life is impossible, for instance, without the brain as a control center to regulate the way our bodies work or without a beating heart to pump blood and oxygen around the body. Modern medicine (surgery in particular) has made it possible to replace or remove some of what traditionally was considered essential to life. It is now possible to live without a lung or kidney or spleen or part of a liver. A dialysis machine can clean our blood in a similar manner to the kidneys. Our hearts can continue beating with pacemakers, or even with a completely new heart from an organ donor. We can replace limbs with prosthetics. In theory, today it is possible to live without arms, legs, eyes, ears, nose, breasts and many of our internal organs, and have a rich life. Still, a wholesome body allows us to experience and interact with the world around us in many different ways that enhance each other and add layers of detail that we may only properly notice when things go wrong. Anatomy is the study of the structure of the body (and its component parts), through which we can learn about the functioning of our body and develop a new appreciation for its complexities.

The anatomical landscape

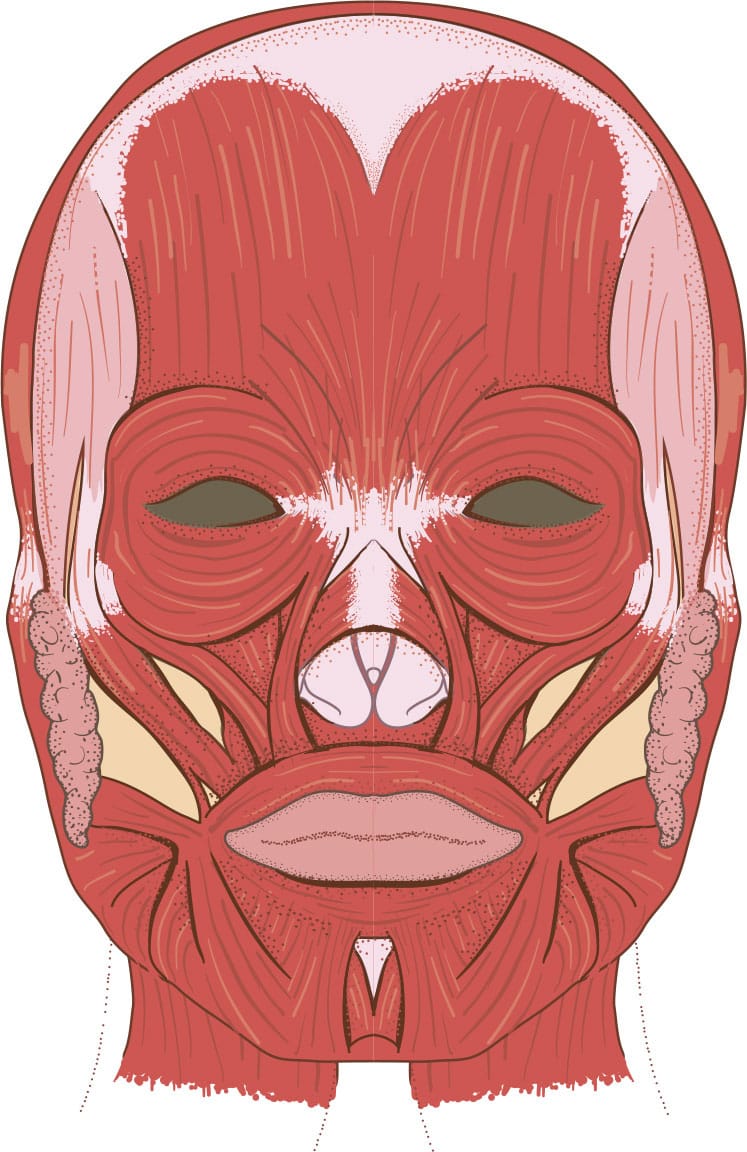

The landscape of the human body has been charted meticulously through untold hours of gruelingand often smellywork by doctors and anatomists of old dissecting decomposing bodies in intolerable conditions. They cut up (anatomy means to cut up) and mapped out the topographical atlas of our body, making their way through unknown territories and recording their findings in painstaking detail, not unlike the voyagers who once traversed the wide and unexplored oceans. Without these pioneers, we would have remained in the dark ages of medical knowledge, our understanding of the human body shrouded in mystery and misunderstanding and subject to superstition. And yet this landscape, despite its relative familiarity to those in the healthcare professions, still remains elusive and somewhat mysterious to many of us, even today.

Through ancient and medieval times, knowledge of the human body remained the secret realm of the few physicians and healers who dedicated themselves to curing ailmentsand, in ancient Egypt, to those who embalmed the bodies of the dead to aid them on their journey in the afterlife. Physicians from ancient times until the 15th century CE observed and treated patients based on an imperfect understanding of what lay under the skin, restricted by law and superstition to looking only skin deep. Animals were dissected initially to understand how the body worked, and only rarely did physicians catch glimpses of internal organs or observe the interplay of structures beneath the skin. Later, when dissection became more commonplace, it remained within the confines of medical establishments and linked to hospitals. Doctor-cum-anatomists dissected to understand the workings of the body during a period when textbooks and illustrated anatomy atlases were still unavailable. Even though public dissection for a time caught the interest of the general public (and, sometimes, the criminal cunning of body-snatching entrepreneurs), it did so in a somewhat grotesque manner, with the shock value of seeing a dead body cut up arguably of more interest to many than actually understanding the intricacies of the human body, particularly as the bodies of criminals were publicly humiliated in this manner. Today, anatomical knowledge is available everywhere, and exhibitions parading plastinated and dissected bodies draw in millions of visitors around the world, revealing closely guarded secrets to the general public and making the body more accessible for learning.

Anatomy in modern times

The true foundation of medicine (and, by extension, all healthcare professions), anatomy is the most concrete of all the sciences healthcare students will encounter in their learning journey. Dissecting the human body used to be a requirement for all medical students in previous times. Today, financial constraints, lack of qualified staff, limited access to donated bodies, and the requirement for complex and cumbersome equipment to embalm and preserve them (as well as stringent regulations around body donations) mean that numerous institutions around the world have cut down foundational anatomy teaching for students. Moreover, where it does happen, instead of full-body dissections, other tools are increasingly utilized, with technology now a significant factor in how the subject is taught. The internet is rife with anatomy video clips and tutorials detailing the secrets of the human body for anyone keen to learn. Countless software applications for smartphones and computers are available to further enhance their knowledge. Digital and paper anatomy textbooks, exquisitely illustrated atlases, lifelike plastic models, virtual reality glasses, and all manner of additional equipment are also competing for attention in anatomy curricula.

Still, the general public and healthcare students (as well as numerous clinicians and anatomists) remain firmly convinced that there is no replacement for learning anatomy from donated bodies. Among other things, none of the other approaches allow the student to learn and appreciate the differences in the human body due to age and sexor to experience the range of common anatomical variants they are likely to encounter in the course of their clinical careers. Instead of requiring students to dissect, many institutions now produce pre-dissected material available for learning. These prosections, as they are called, may be embalmed or plastinated (longer-lasting). Surgeons may train on fresh-frozen bodies donated specifically for this purpose, as these are more realistic for learning procedures. Access to donated bodies to dissect or learn anatomy from through prosections is still a valuable experience for students, not solely for the tactile feedback they get from direct handling of body tissues and perceptions of depth that can only really be appreciated with a hands-on approach, but as a rite of passage and a formative experience in learning how to be professional and sensitive when faced with death and dying, the bread and butter of most healthcare professions.