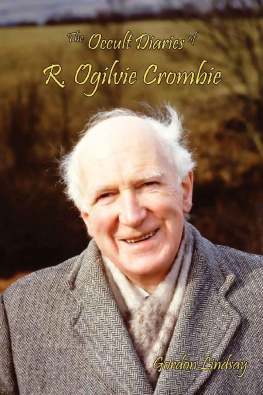

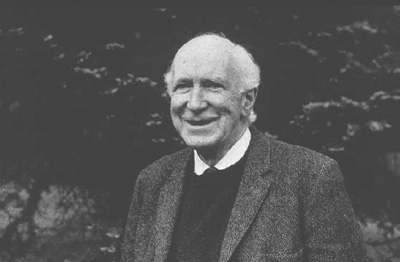

Ogilvie, the Merlin figure, surely to us is Gandalf, the White Magician.

SIR GEORGE TREVELYAN

CONTENTS

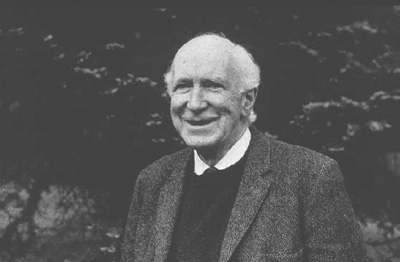

Robert Ogilvie Crombie, or Roc, was a loving and gentle man, a wondrous storyteller, a musician, an actor, and an embodiment of the best of Scottish charm. He was the wise old man, the grandfatherly figure children adore, and the magician who guides heroes and heroines on their paths of accomplishment. He was a man of culture who had one foot in this world and one foot in the worlds of spirit and mystery.

There was a great deal to admire about Roc. He was a self-taught mythologist, psychologist, historian and esotericist, though his early training had been in science. Though quiet and reserved, he was still a pleasure to be with. He had a delightful, even impish, sense of humour matched by a twinkle in his eyes that was rarely absent.

DAVID SPANGLER

PROLOGUE

How it all began

MIKE SCOTT, MUSICIAN, WRITER AND ARCHIVIST

R Ogilvie Crombie was an Edinburgh man, born in that most gracious of cities into an artistic, well-to-do family in the spring of 1899. As a child he played piano, excelled at maths and science, and read the books on parapsychology he found in his fathers library, an interest that developed into teenage experiments in telepathy and automatic writing. But though young Ogilviethe R stood for Robert but his friends called him by his middle nameenjoyed rambling over the Braid Hills that lay south of the family home, he was not a hardy lad. When he was nine it was discovered his heart had a leaking mitral valve, a condition for which in those days there was no treatment.

Thus, at a young age, the major strands of Ogilvies life were established: the arts and sciences, a fragile heart and an interest in the unseen.

On leaving school in 1915 he joined the Marconi radio company as a trainee, then served as a radio operator in the Merchant Navy during the latter part of the First World War. At wars end he went to Edinburgh University where he studied physics, chemistry and mathematics, but after three years Ogilvies studies were curtailed by illness. When he was thirty-three, he suffered a serious heart attack and was told by his doctor to consider himself retired. Prevented from working, Ogilvie was free to dedicate himself to his interests, and immersed himself in the cultural life of Edinburgh. He was a founding member of the famous Scottish theatre group The Makars, and in the 1930s became, as one newspaper said, a well-known personality in Edinburgh dramatic circles. He also wrote and directed plays and in later years regularly appeared on Scottish television playing small character partsa judge here, a professor there. His credits included popular series such as Dr Finlay's Casebook, and he appeared as an extra in the Peter Sellers movie The Battle of the Sexes, where he can be briefly glimpsed strolling up Edinburghs Royal Mile.

Ogilvie was that rare kind of man who is interested in everything. He performed piano recitals, led a choir, edited poetry journals and formed a philosophical society. In his rich Edinburgh brogue he gave talks on classical music and the appreciation of paintings. He kept abreast of developments in science and medicine, wrote letters to newspapers, and followed all of the arts with a sharp eye. Yet running ever parallel with these pursuits, and as private as his enjoyment of acting was public, was Ogilvies interest in the deeper mysteries of life.

There is no doubt that Ogilvie was an initiate of an ancient and veiled spiritual tradition. His lectures and writings of the 1960s and 70s, which comprise the major part of this book, intermingled with recollections by others who were there, bear the hallmarks of the adept: authority, humility, curiosity, encyclopaedic yet integrated knowledge, and the tantalising sense of greater wisdom held perpetually in reserve behind a nuanced boundary of well-weighed words. It is not known to which school or system he belonged, nor is it important. Ogilvie never revealed his spiritual lineage, but is clear he had a profound understanding not only of what used to be called the occult but of all the worlds major religions, and many of its more obscure ones.

This sheathed mastery was matched by Ogilvies profound understanding of nature, which sprang from his scientific interests and his lifelong love of hill walks, fresh air and bathing in the sea. Ogilvies empathy with the natural world deepened significantly during his ten-year experience of living in an isolated rural cottage. Ordered out of Edinburgh by his doctor at the outbreak of the Second World War, lest his fragile health be broken in the event of German bombings, Ogilvie lived an ascetic life in Cowford Cottage, Perthshire. There was no electricity and he fetched his water from a nearby spring, but the absence of modern comforts and the immanent presence of nature acted powerfully upon the curious and sensitive Ogilvie, who gradually became more and more subtly aware of the natural world around him. By oil lamp and candle he studied Jung and Plato, and among the multitude of books he read was Paramahansa Yoganandas then newly published Autobiography of a Yogi. And though he kept in touch with the distant fortunes of humanity by newspapers and radio, Ogilvie existed for those ten years not unlike a medieval hermit: removed from the tides of men and alert to the deeper rhythms of the world.

He returned to Edinburgh in 1949 and lived in a first-floor flat on Albany Street, close to the city centre, where he would stay until his death in 1975. Most of the experiences recounted in this book occurred during the last decade of his life, and it was during this period that Ogilvie made the only public displays of his interest in occult matters. These took the form of lectures and were spurred in part by his friendship with a former RAF officer named Peter Caddy and his subsequent involvement in the spiritual community of which Caddy was co-founder, the Findhorn Foundation in northeast Scotland.

Though today world-renowned and numbering hundreds of members, at the time Ogilvie met Caddy the community at Findhorn comprised five adults whose little-known work was centred around two mystical yet practical activities. Peter, his wife Eileen and their friend Dorothy Maclean had been trained in a variety of spiritual disciplines, and Eileen and Dorothy had each learned to contact personal inner sources of guidance in meditation. The experience of an inner guiding voice is common to all spiritual traditions, and was termed by Eileen the still small voice within. Following the directions Eileen received inwardly, Peter had unconventionally but successfully managed a large Scottish hotel for several years, and the group was now establishing their fledgling community the same way.

In 1963 their work had expanded into a dynamic cooperation with nature when Dorothy discovered, also in meditation, that like a human radio receiver she could tune into and contact the overlighting angelic spirits of plants, subtle intelligences she called devas. Short of cash and struggling to grow food in their meagre garden, Peter persuaded a bemused Dorothy to ask the devas for planting advice. And the devas responded. Soon, amazingly, the Findhorn group was receiving precise gardening instructions from the inner intelligences of nature, resulting, by the mid 60s, in an astonishingly abundant garden grown in the unlikely sandy soil of a wind-lashed caravan park. This miraculous Findhorn garden had profound implications not only spiritually, but for ecology, land reclamation and food creation; if humanity and nature could cooperate like this around the world, what might be achieved? The small group wasnt yet ready to reveal their secret for fear of disbelief and ridicule; nevertheless, the garden became famous when a parade of horticultural experts, first local then national, visited and pronounced themselves stunned and mystified.

Next page