One of the greatest living teachers of Dzogchen, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, explains one of the most profound texts of this tradition (Patrul Rinpoches Three Keys), and the teaching is translated by one of Americas leading scholars, Jeffrey Hopkins. Does it get any better than this?

Jos I. Cabezn, author of The Buddhas Doctrine and the Nine Vehicles

Despite the alleged sectarianism of Tibetan Buddhism, there has been a long history of mutual influence and inspiration across the traditions. Over the course of the past four hundred years, one of the most famous has been the study and practice of Dzogchen by the lineage of the Dalai Lamas. It continues to the present day, as this volume eloquently attests.

Donald S. Lopez Jr., author of From Stone to Flesh: A Short History of the Buddha

ABOUT THE BOOK

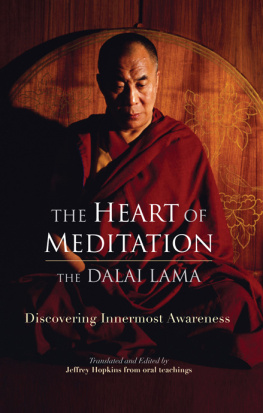

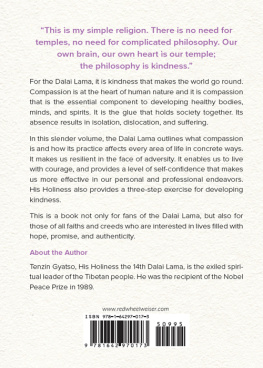

The heart of meditationthe thing that brings it aliveis compassion. Without that essential foundation, other practices are pointless. Fortunately, the mind can be trained in compassion, and the mind thus trained with the qualities of love, empathy, kindness, and respect for others is ready for the practice of the Great Completeness (Dzogchen), which is considered the pinnacle of spiritual practice in the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. His Holiness the Dalai Lama here teaches the Great Completeness simply but thoroughly, using as his reference a visionary poem by the nineteenth-century master Patrul Rinpoche to show that insight can never be separated from compassion. Through practice of the Great Completeness, we can access our innermost awareness and live our lives in a way that acknowledges it and manifests it. The wisdom and compassion that arise from such insight are critical, His Holiness teaches, not only to individual progress in meditation but to our collective progress toward peace in the world.

Sign up to receive weekly Tibetan Dharma teachings and special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/edharmaquotes.

The

HEART

of

MEDITATION

Discovering Innermost Awareness

T HE D ALAI L AMA

Translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins from oral teachings

A teaching on Patrul Rinpoches Three Keys Penetrating the Core

S HAMBHALA

BOULDER

2016

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2016 by The Dalai Lama Trust

Cover design: Jim Zaccaria

Cover art: Catherine Cabrol/Kipa/Corbis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Bstan-'dzin-rgya-mtsho, Dalai Lama XIV,

1935- author. | Hopkins, Jeffrey.

Title: The heart of meditation : discovering innermost awareness /

The Dalai Lama ; translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins.

Description: First edition. | Boulder : Shambhala, 2016. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015021940 | eISBN 978-0-8348-4021-8 | ISBN 9781559394536 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Rdzogs-chen. | BISAC: RELIGION /

Buddhism / Tibetan. |

RELIGION / Buddhism / Rituals & Practice. | RELIGION /

Buddhism / Sacred Writings.

Classification: LCCBQ 7935.B774 H45 2016 | DDC 294.3/4435dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015021940

CONTENTS

T HIS IS AN extraordinary book in which His Holiness the Dalai Lama provides intimate details on meditation. In preparation for a teaching in London in the summer of 1984 on a visionary poem by a profound Tibetan yogi, His Holiness taught me this text in his Private Office in Dharamsala, India, since I was to serve as his interpreter for the public talk. In this book, I have interwoven these private teachings with the Dalai Lamas seminar lectures in Camden Centre, which affords readers a compelling picture about how to put themselves into a deep state beyond the confining coverings of too much thought, released into the naked core of innermost mind. The aim is to make use of the space between thoughts to experience a deeper level of basic awareness and bring it to the fore, realizing the floor of all conscious experience.

The book is structured in four parts. In the first, the Dalai Lama provides the context of the extraordinarily direct instructions of the poem by fleshing out the advice given at its end to train in empathy for all beings and in knowledge of the nature of all phenomenapersons and objects. In the second, he introduces the system of the Great Completeness and identifies innermost awareness as the fundamental principle common to all orders of Tibetan Buddhism. In the third, he comments on the inspired poem, opening up its meaning by expanding on the three keys that are its essential messagehow to identify innermost awareness within yourself, how to maintain contact with innermost awareness in all states, and how to release yourself from too much thought. You will easily see the common thread of the first three parts: by expanding compassionate empathy for all beings, you break down barriers that draw us into myriad counterproductive destructive thoughts and actions, and by exploring the nature of the mind, oneself, and objects, you undermine the lure of their seductive concreteness, making it possible to make use of the space between thoughts and allow a deeper mind to manifest. In the fourth, he provides more explanation about special spiritual topics such as the two truthsconventional and ultimate, purity from the start, inward and outward luminosity, the gradual diminishment of conceptuality and the increase of actualization of innermost awareness, and identifying the clear light in the midst of any consciousness. The four parts reinforce each other; therefore you may want to read around in them at will.

Let me add that the stay in London for the lectures in Camden Centre was most interesting for me. My ancestors on both sides, the Hopkins and Adams, were in America from the time of the Revolution and both traced their roots to England, and my fascination with the ancestral home stemmed mainly from wanting to see if I felt any bond at all with the English. The Dalai Lama was staying at the home of the pacifist, ecumenist, and feminist the Very Reverend Edward F. Carpenter, dean of Westminster (from 1974 to 1986), and his wife Lilian, both of whom I quickly found to be very warm and open. I was put up at the Liberal Club a few blocks away, having to walk past Downing Street, home and office of the prime minister, where my inner juvenile delinquent would make me take a few steps toward Number 10 and pause long enough to make the security edgy.

On July 2, Lilian Carpenter guided me through the magisterial but awfully gray Westminster Abbey with pleasant and sometimes jovial conversation. We had a lovely time, enjoying each others company, all the while identifying the history of the great leaders of England commemorated around us in great blocks of stone, though I have to admit that I felt more and more estranged from my ancestors, despite feeling more and more at home with her.

The next day I returned to Westminster Abbey to interpret for His Holiness. A boys choir sang with the angelic voices of youth, and His Holiness was introduced. The first sentence he spoke to the assembled audience in this great abbey was in Tibetan: I do not care about buildings, and he waved his hand ever so slightly to indicate that he meant this very building, sweeping to heaven above us. This, in effect, was his first public statement in London; he said no more, pausing for my translation. I had no idea where he was going, what was to follow, so I had no context. I am a firm believer in translating exactly what a lama says, although context allows for some choice of words. But here I had none; my only context was how much this building meant to the audience! But that did not matter. At issue was his point, so I had to translate exactly what he said, and I did. This was his second visit to England, but the first was not for teaching, so the audience had no context either. The response seemed to be totally flat; to look at their faces, it was as if he had not said anything. His Holiness continued, My interest is in what is happening in your mind, your heart. When he says this nowadays, there is instant recognition, a deep sense of acknowledgment, but then and there in Westminster Abbey, as I watched the audience, their response still seemed to be flat. If anything was happening, it was underneath, but in time it was obvious that the audience warmed.

Next page