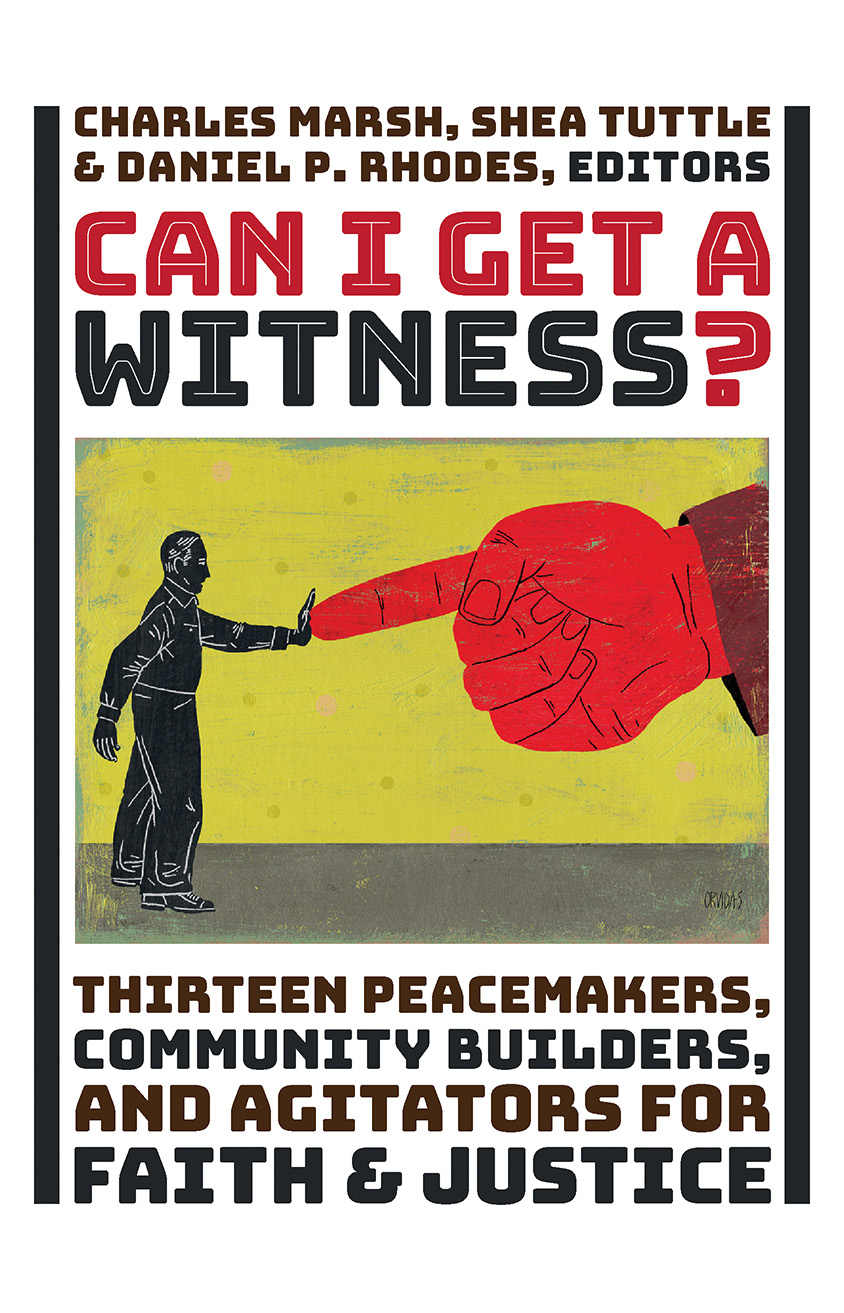

CAN I GET A WITNESS?

Thirteen Peacemakers, Community Builders,

and Agitators for Faith and Justice

Edited by

Charles Marsh, Shea Tuttle,

and Daniel P. Rhodes

WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY

GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

4035 Park East Court SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546

www.eerdmans.com

2019 Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

All rights reserved

Published 2019

252423222120191234567

ISBN 978-0-8028-7573-0

eISBN 978-1-4674-5263-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

For these thirteen witnesses,

and for the cloud of witnesses

too great to know, too numerous to name,

so broad as to occasion holy surprise and reforming delight.

May these stories honor you.

Contents

This book represents a collaboration of theologians, writers, and editors over two successive years in Charlottesville and Chicago, who were seeking to retrieve and celebrate the tradition of Christian social progressives in the United States. The editors are grateful to each of the contributors for bringing this rich cast of characters to life and for answering the question Can I get a witness? with a resounding yes.

We owe huge thanks to Jessica Seibert, the project manager at the University of Virginias Project on Lived Theology. Her brilliant organizing made the meetings happen, and she continued to offer limitless support and smart editorial advice in the months since. Koonal Patel and Gosia Czelusniak, the excellent team at Loyola University Chicagos Institute of Pastoral Studies, assisted Jessica in invaluable ways in preparation for our meeting at the Water Tower Campus.

Editor extraordinaire Lil Copan shepherded us through the drafting and first revision of the manuscript with her sharp eye and generous intelligence. We are grateful to David Bratt, Anita Eerdmans, Holly Knowles, Jeremy Cunningham, Leah Luyk, Alexander Bukovietski, and the whole Eerdmans team for their attentive and encouraging partnership. We are delighted this book landed in their exceedingly capable hands.

The Project on Lived Theology exists thanks to the generosity of the Lilly Endowment and theological vision of Jessicah Duckworth and Chris Coble. We are ever so grateful to count them among our cloud of witnesses.

Charles Marsh and Shea Tuttle

When Dietrich Bonhoeffer came to Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan as a visiting student and postdoctoral fellow in the late summer of 1930, he was a straight-arrow scholar whose star was rising. His sights were set on a lifetime of academic accomplishments and the rich rewards of the guild. He didnt think there was anything he could learn from the American Protestant churches who worshipped a god tailored for their middle-class tastes and preferences.

But when he left New York ten months later, he left with a dramatically transformed perspective on social engagement, faith, and historical responsibility. He began to put aside his professional ambitions and look for resources in the Christian (and increasingly in the Jewish) tradition that could inspire and sustain dissent and civil courage. A technical terminology that had distinguished his writings and teaching before 1930 began to fade, and in its place emerged a language more direct and expressive of lived faith.

In Tegel prison in 1944, incarcerated for his role in a plot to assassinate Hitler, Bonhoeffer recalled the first American visit as one of the decisive and transformative influences in his life. I dont think Ive ever changed very much, he wrote, except perhaps at the time of my first impressions abroad.... It was then that Something had happened in America, as Bonhoeffers best friend and biographer Eberhard Bethge later wrote.

Over the course of that transformative year in the United States, Bonhoeffer encountered the strange and unfamiliar world of radical Christianity, represented at the time by the Protestant social theology taught and practiced at Union Seminary; the American organizing tradition, flourishing in New York and in an ever expanding network of progressive Christian activism; and the African American church, where he said he finally heard the gospel of Jesus preached with power and conviction. Five months into the school year he told a friend that he had come in search of a cloud of witnesses.

The cloud of witnesses that he found comprised the largely forgotten tradition of a confessional left: activist theologians, Bible-wielding labor organizers, social gospel reformers, and African American preacherswhich is to say, the cast of characters foregrounded in Can I Get a Witness? Bonhoeffers encounter with this tradition transformed his sense of vocation, enabled him to do theology closer to the ground, and set him on the difficult road that would ultimately lead to Flossenbrg concentration camp.

***

The stories of the churchs peacemakers, community builders, and inside agitators, those who refuse to remain spectators of the panorama of injustice,any money. Yet we are confident that their examples will outlast those of the multitudes scrambling to see who can bow down first to country, or party, or profit, or another reigning idol of the day.

It is a good time to remember the peculiar people, dissidents, misfits, and malcontents who sing strange and beautiful songs of Gods peaceable kingdom. Being peculiar has never been easy, but in this second decade of the twenty-first century, amid the violent convulsions and linguistic political confusions of Christian witness in the United States, the testimonies of dissidents take on new urgency. These are challenging days for those who affirm the integrity of the global, ecumenical church; read the Bible against the principalities and the powers; and dare to speak against the day.

Peculiarity is not a quality intended to highlight the feeling of specialness, as in the conceited notion that we are peculiar because we are Gods chosen ones. The stories of Scripture make clear that much is expected of those who call on or claim relationship with God. Being peculiar, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, means being a people who practice mercy and seek justice. Only the nation that defends the defenseless, establishes equity, and relieves the oppressed is chosen. This is the message of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible.

Many of the earliest writings on the identity of the people who call themselves followers of Christ convey bewilderment at the new moral habits of the Christian community. They live in the cities and countries of the empire but as sojourners; they bear their share in all things as citizens, and they endure all hardships as strangers. Yet they display a wonderful and confessedly striking method of life.

Living as strangers in a strange land, as the peculiar people in this volume vividly attest, is not about withdrawal from the world or resignation to injustices. It is rather about learning to act and to think, to read and to interpret, to organize and to vote in the new light springing from the teachings and life of Jesus. It means bearing witness to the authenticity of our faith and building hope in the practices we keep: showing hospitality to strangers and outcasts; affirming the unity of the created order; reclaiming the ideals of beauty, love, honesty, and truth; and embracing the preferential option for nonviolence. It means participating in the world in such a way as to affirm it as Gods good creationand to labor to make it ever more so. It means living in the expectation of Gods ongoing advent among us to make all things new.