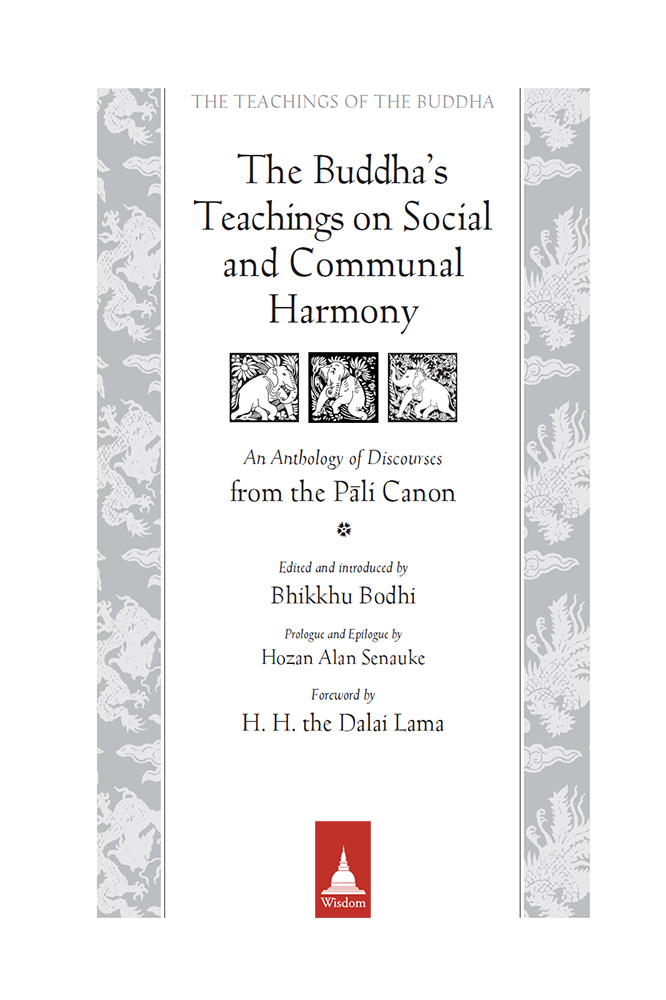

THE TEACHINGS OF THE BUDDHA SERIES

The Connected Discourses of the Buddha:

A Translation of the Sayutta Nikya

Great Disciples of the Buddha:

Their Lives, Their Works, Their Legacy

In the Buddhas Words:

An Anthology of Discourses from the Pli Canon

The Long Discourses of the Buddha:

A Translation of the Dgha Nikya

The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha:

A Translation of the Majjhima Nikya

The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha:

A Translation of the Aguttara Nikya

What advice would the Buddha give us in todays world of conflict and strife?

I N THIS VOLUME acclaimed scholar-monk Bhikkhu Bodhi has collected and translated the Buddhas teachings on conflict resolution, interpersonal and social problem-solving, and the forging of harmonious relationships. The selections, all drawn from the Pli Canon, the earliest record of the Buddhas discourses, are organized into ten thematic chapters. The chapters deal with such topics as the quelling of anger, good friendship, intentional communities, the settlement of disputes, and the establishing of an equitable society. Each chapter begins with a concise and informative introduction by the translator that guides us toward a deeper understanding of the texts that follow.

In times of social conflict, intolerance, and war, the Buddhas approach to creating and sustaining peace takes on a new and urgent significance. Even readers unacquainted with Buddhism will appreciate these ancient teachings, always clear, practical, undogmatic, and so contemporary in flavor. The Buddhas Teachings on Social and Communal Harmony will prove to be essential reading for anyone seeking to bring peace into their communities and into the wider world.

Through scholarship and wise discernment Bhikkhu Bodhi has chosen a set of discourses that uncover and make clear the Buddhas approach to social affairs. A timely and powerful resource for all varieties of peace work, this is a fantastic inspiration for all who wish to foster a more harmonious world.

SHARON SALZBERG, author of Lovingkindness

Publishers Acknowledgment

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution of the Hershey Family Foundation toward the publication of this book.

Foreword

BY HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA

The historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, lived, attained enlightenment, and taught in India more than 2,500 years ago. However, I believe that much of what he taught so long ago can be relevant to peoples lives today. The Buddha saw that people can live together freely as individuals, equal in principle and therefore responsible for each other.

He saw that the very purpose of life is to be happy. He talked about suffering in the context of ways to overcome it. He recognized that while ignorance binds beings in endless frustration and suffering, the development of understanding is liberating. The Buddha saw that every member of the human family, man and woman alike, has an equal right to liberty, not just in terms of political or even spiritual freedom, but at a fundamental level of freedom from fear and want. He recognized that each of us is just a human being like everyone else. Not only do we all desire happiness and seek to avoid suffering, but each of us has an equal right to pursue these goals.

Within the monastic community that the Buddha established, individuals were equal, whatever their social class or caste origins. The custom of walking on alms round served to strengthen the monks awareness of their dependence on other people. Within the community, decisions were taken by vote and differences were settled by consensus.

The Buddha took a practical approach to creating a happier, more peaceful world. Certainly he laid out the paths to liberation and enlightenment that Buddhists in many parts of the world continue to follow today, but he also consistently gave advice that anyone may heed to live more happily here and now.

The selections from the Buddhas advice and instructions gathered here in this book under headings related to being realistic, disciplined, of measured speech, patient rather than angry, considerate of the good of others all have a bearing on making friends and preserving peace in the community.

We human beings are social animals. Since our future depends on others we need friends in order to fufil our own interests. We do not make friends by being quarrelsome, jealous, and angry, but by being sincere in our concern for others, protecting their lives, and respecting their rights. Making friends and establishing trust are the basis on which society depends. Like other great teachers the Buddha commended tolerance and forgiveness in restoring trust and resolving disputes that arise because of our tendency to see others in terms of us and them.

In this excellent book Bhikkhu Bodhi, a learned and experienced Buddhist monk, has drawn on the scriptures of the Pli tradition, one of the earliest records of the Buddhas teachings, to illustrate the Buddhas concern for social and communal harmony. I am sure Buddhists will find the collection valuable, but I hope a wider readership will find it interesting too. The materials gathered here clearly demonstrate that the ultimate purpose of Buddhism is to serve and benefit humanity. Since what interests me is not converting other people to Buddhism, but how we Buddhists can contribute to human society according to our own ideas, I am confident that readers simply interested in creating a happier, more peaceful world will also find it enriching.

The Dalai Lama

Prologue

BY HOZAN ALAN SENAUKE

Gotama Buddha came of age in a land of kingdoms, tribes, and varna, meaning social class or caste. It was a time and place both distinct from and similar to our own, in which a persons life was strongly determined by social status, family occupation, cultural identity, and gender. Before the Buddhas awakening, identity was definitive. If one was born into a warrior caste or that of a merchant or a farmer or an outcast, one lived that life completely and almost always married someone from the same class or caste. Ones children did the same. There was no sense of individual rights or personal destiny, no way to manifest ones human abilities apart from a societal role assigned at birth. So the Buddhas teaching can be seen as a radical assertion of individual potentiality. Only by ones effort was enlightenment possible, beyond the constraints of caste, position at birth, or conventional reality. In verse 396 of the Dhammapada, the Buddha says:

I do not call one a brahmin only because of birth, because he is born of a (brahmin) mother. If he has attachments, he is to be called only self-important. One who is without attachments, without clinging him do I call a brahmin.

At the same time, the Buddha and his disciples lived in the midst of society. They didnt set up their monasteries on isolated mountaintops but on the outskirts of large cities such as Svatth, Rjagaha, Vesl, and Kosamb. They depended on laywomen and men, upsik and upsaka, for the requisites of life. Even today monks and nuns in the Theravda tradition of Burma (or Myanmar), Thailand, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, and Laos go on morning alms rounds for their food. Although they keep a strict monastic discipline, it is mistaken to imagine that Southeast Asian monasteries are cloistered and apart from their brothers and sisters in the secular world. Monasteries and secular communities are mutually dependent, in a tradition that is sweet and fully alive.

Next page