This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Translators Introduction

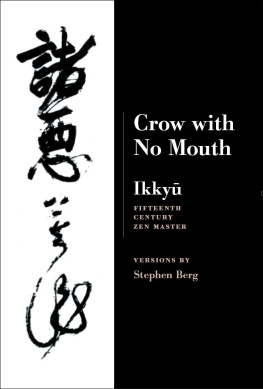

Ikky is unique in Zen for letting his love of all appearance occupy him until it destroys any possibility for safety or seclusion. In his poetry, he turns the eye of enlightenment to all phenomena: politics, pine trees, hard meditation practice, sex, wine. The poems express the unborn bliss of his realization and equally his devastation at the horrors of this world. From this union of bliss and heartbreak he rails without hatred against hypocrisy, corruption, and bad religion, he consorts free of lust with prostitutes and musicians. His awakening outshines the small idols of reason, emotion, self, desire, doctrine, even of Buddhism itself.

We translate Ikky because we love that shine, which is his mind. It is unbound, uncorrupt, effulgent, playful, and recondite. We hope to transmit something of its quality to an English-reading audience.

We dont know much about the human being we call Ikky. The Chronology of the Monk Ikky of the Eastern Sea, written by a disciple, gives only a year-by-year outline of Ikkys public life. It tells us that he was the son of a seventeen-year-old Emperor by a palace concubine, born auspiciously on New Years Day 1394the first of February by the Gregorian calendar. If this is so, then the story is at once political: one hundred years previous, an Emperor had rebelled against his generals, establishing an exile Southern Court in opposition to their Northern Court in Kyt. The split was only repaired a century after Ikkys death by the reunification of Japan under the Tokugawa. Ikky lived through recurrent civil wars: periodic vast starvation, the burning of Kyt, and fragile armistices when both sides reached exhaustion. Ikkys mother is said to have been a Southern aristocrat, a peace offering; Northern jealousies saw a knifeup both her sleeves. She and Ikky were thus soon banished to the Long Gate Palace, seat of disfavored concubines, and his imperial patrimony concealed.

At age five, Ikky went alone into a minor Kyt monastery, where he received a good educationthat is, he was trained in Buddhist doctrine and the high cultures of China. In particular, he learned to compose classical poetry in that language. (The poems we translate here are all of that genre.) Zen monasteries of the period functioned in ways reminiscent of the medieval European church. They were lavishly patronized, rich in land and peasant farmers, traders in luxury goods, repositories of culture and its accoutrements, and perfectly interpenetrated by the concerns of their political lords. These make a poor home for serious Zen practice, and Ikkys home temple Daitoku-ji was no exception. At sixteen years old, he quit in disgust and for the next fifteen years trained in poverty under the two most exacting Zen masters he could find. In the end both masters were dead, and he had attained his first enlightenments and the name Ikky  , meaning Having Once Paused.

, meaning Having Once Paused.

For the next fifty years he lived in and around Kyt and Sakai, a suburb of modern saka whose merchant and artistic cultures parallel Renaissance Venice. He remained an outsider to established religion, ever disgusted by its cant and compromise. Im just as likely to be found in a brothel as a temple, he wrote. Though we know him best through his poetry, he also collaborated intensively with artists who were reworking the whole of the medieval aesthetic. His influence shaped their calligraphy, Noh theater, linked verse, tea ceremony, and rock gardening, all of which now define Japans sense of its cultural tradition.

In this book we translate some fifty poems, divided into four slightly overlapping sections. The first consists of poems dedicated to Zen masters of China and Japan, lineage founders who preceded Ikky and whose tradition lives in him. The great Linji, whom Japanese call Rinzai, is prominent among them, but a dozen more sublime masters also appear.

Second is a set of poems containing the term fry . Its a two-syllable word: f is pronounced foo, and ry is pronounced like the English word cue, but with an r in the place of the c. Itsliteral meaning is the flow of wind, but it holds within itself a grand expanse of human exploration. In a China some thousand years before Ikky, it was a style of elegant sensuality. Soon, though, its elegance emerged as the refinements of eremitic joy and simple beauty. Japan played out both its gaudiness and restraint. Ikky upholds all these usages and then subsumes them under a higher one: fry is his heart-broken appreciation for the play of appearance, for mystery. Its the center of his aesthetic, and he shows it differently in each poem. We have therefore left it untranslated. The subsequent essay, by Traktung Yeshe Dorje, expands on the term.

. Its a two-syllable word: f is pronounced foo, and ry is pronounced like the English word cue, but with an r in the place of the c. Itsliteral meaning is the flow of wind, but it holds within itself a grand expanse of human exploration. In a China some thousand years before Ikky, it was a style of elegant sensuality. Soon, though, its elegance emerged as the refinements of eremitic joy and simple beauty. Japan played out both its gaudiness and restraint. Ikky upholds all these usages and then subsumes them under a higher one: fry is his heart-broken appreciation for the play of appearance, for mystery. Its the center of his aesthetic, and he shows it differently in each poem. We have therefore left it untranslated. The subsequent essay, by Traktung Yeshe Dorje, expands on the term.

Third is a set of nine poems that Ikky wrote on the night of 18 October 1447. They are among his few writings we can date with certainty. Daitoku-ji had been nearly alone among Buddhist establishments in retaining the right to appoint its abbot from within, thus controlling the intrusion of political powers. When this privilege was rescinded on a technicality, the monks rioted. Ikky, in turn, walked out of Kyt and began a hunger strike, recorded in this poem cycle.

Finally there are a dozen poems to his lover Mori. They met when he was in his seventies, she a blind musician in her thirties or forties. They lived together until Ikkys death eleven years later. We know her almost exclusively through his poetry. She appears there only as Mori, which is her surname, or as the attendant Mori, or simply as the blind woman.

A thousand of Ikkys poems are gathered in the Crazy Cloud Collection and its addenda. Its not unusual that he wrote in classical Chineseit was the language in which Buddhism had come to Japan, and many important texts, religious or otherwise, continued to be written in it. His chief model was the four-line Regulated Verse of Tang China, a poem-form with five or seven words per line. Rhyme, rhythm, tonal pattern, and parallelism are all prescribed; diction and subject-matter are also controlled. All well-educated people wrote such poetry, with results varying from the inspired to the very ordinary. Another model for Ikky was the Sanskrit-derived gatha, short poems attesting to ones awakening. The first poem we translate in this book is the gatha Ikky wrote for his teacher Kas, when he was enlightened at age twenty-six.

The Buddhist practitioner has been called a lotus, growing pure and fragrant from the muck of a swamp. But in these poems Ikkyis swamp and lotus both: he cannot be sullied by circumstance, by birth and death, by identity, by either impurity or purity. His ongoing moment of enlightenment changes how this world appears. If we are deluded, we see mostly its degrading forces. But in unborn wisdom mind, the great one-thousand worlds manifest from primordial purity, writes Ikky. Thus, When I enter a brothel, I display this same great wisdom.

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper , meaning Having Once Paused.

, meaning Having Once Paused. . Its a two-syllable word: f is pronounced foo, and ry is pronounced like the English word cue, but with an r in the place of the c. Itsliteral meaning is the flow of wind, but it holds within itself a grand expanse of human exploration. In a China some thousand years before Ikky, it was a style of elegant sensuality. Soon, though, its elegance emerged as the refinements of eremitic joy and simple beauty. Japan played out both its gaudiness and restraint. Ikky upholds all these usages and then subsumes them under a higher one: fry is his heart-broken appreciation for the play of appearance, for mystery. Its the center of his aesthetic, and he shows it differently in each poem. We have therefore left it untranslated. The subsequent essay, by Traktung Yeshe Dorje, expands on the term.

. Its a two-syllable word: f is pronounced foo, and ry is pronounced like the English word cue, but with an r in the place of the c. Itsliteral meaning is the flow of wind, but it holds within itself a grand expanse of human exploration. In a China some thousand years before Ikky, it was a style of elegant sensuality. Soon, though, its elegance emerged as the refinements of eremitic joy and simple beauty. Japan played out both its gaudiness and restraint. Ikky upholds all these usages and then subsumes them under a higher one: fry is his heart-broken appreciation for the play of appearance, for mystery. Its the center of his aesthetic, and he shows it differently in each poem. We have therefore left it untranslated. The subsequent essay, by Traktung Yeshe Dorje, expands on the term.