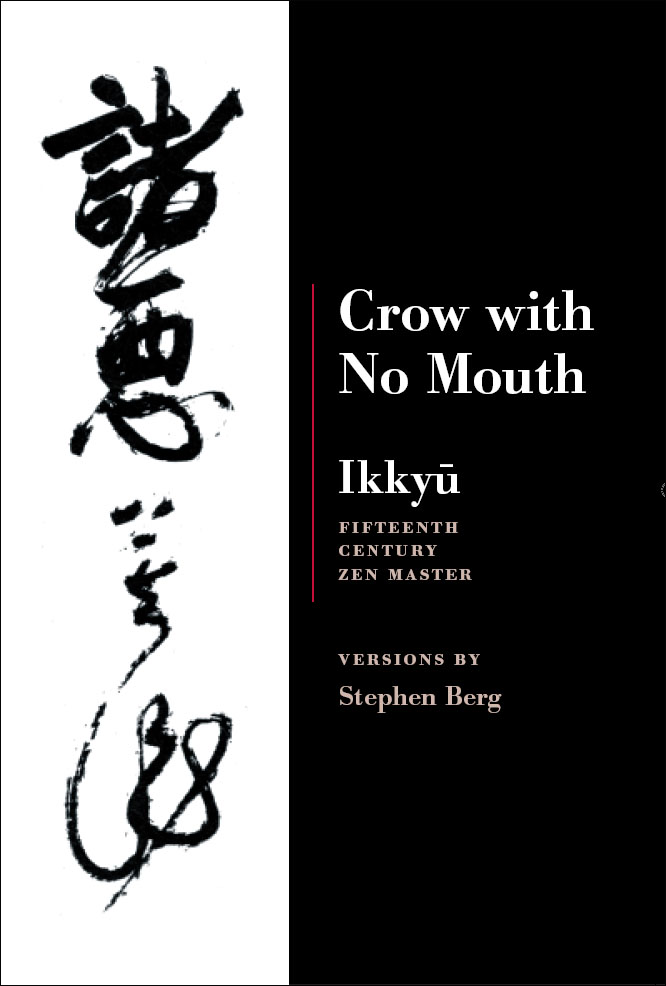

Copyright 1989 by Stephen Berg All rights reserved Cover art: Calligraphy by Ikky,: Do no Evil. ISBN: 978-1-55659-152-5 eISBN: 978-1-61932-076-5 Support Copper Canyon Press: If you have enjoyed this title, please consider supporting Copper Canyon Press and our dedication to bringing the work of emerging, established, and world-renowned poets to an expanding audience through e-books: www.coppercanyonpress.org/pages/donation.asp Contact Copper Canyon Press: To contact us with feedback about this title send an e-mail to: Note to the Reader Copper Canyon Press encourages you to calibrate your settings by using the line of characters below, which optimizes the line length and character size: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Pellentesque euismod magna Please take the time to adjust the size of the text on your viewer so that the line of characters above appears on one line, if possible. When this text appears on one line on your device, the resulting settings will most accurately reproduce the layout of the text on the page and the line length intended by the author. Viewing the title at a higher than optimal text size or on a device too small to accommodate the lines in the text will cause the reading experience to be altered considerably; single lines of some poems will be displayed as multiple lines of text. Thank you. Thank you.

We hope you enjoy these poems. This e-book edition was created through a special grant provided by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. Copper Canyon Press would like to thank Constellation Digital Services for their partnership in making this e-book possible. Hearing a crow with no mouth Cry in the deep Darkness of the night, I feel a longing for My father before he was born. from A Zen Harvest, translated by Siku Shigematsu Preface When Ninagawa-Shinzaemon, linked verse poet and Zen devotee, heard that Ikky, abbot of the famous Daitokuji in Murasakino (violet field) of Kyoto, was a remarkable master, he desired to become his disciple. He called on Ikky, and the following dialogue took place at the temple entrance: Ikky: Who are you? Ninagawa: A devotee of Buddhism.

Ikky: You are from? Ninagawa: Your region. Ikky: Ah. And whats happening there these days? Ninagawa: The crows caw, the sparrows twitter. Ikky: And where do you think you are now? Ninagawa: In a field dyed violet. Ikky: Why? Ninagawa: Miscanthus, morning glories, safflowers, chrysanthemums, asters. Ikky: And after theyre gone? Ninagawa: Its Miyagino (field known for its autumn flowering).

Ikky: What happens in the field? Ninagawa: The stream flows through, the wind sweeps over. Amazed at Ninagawas Zen-like speech, Ikky led him to his room and served him tea. Then he spoke the following impromptu verse: I want to serve You delicacies. Alas! the Zen sect Can offer nothing. At which the visitor replied: The mind which treats me To nothing is the original void A delicacy of delicacies. Deeply moved, the master said, My son, you have learned much.

Speaking those words, perhaps Ikky recalled harsh treatment he received from his second master, Kas Sdon, in the very same circumstances. Kas had ignored him completely while he waited five days outside his temple gate, then had disciples pour water over his head. It would have taken much more to discourage this would-be disciple. Finally Kas agreed to take him on. It could not have been his kindly disposition that encouraged Ninagawa to approach Ikky, whose reputation was fierce. Rather all he heard of the great master, famed painter and poet, suggested such an approach might please Ikky, which proved to be the case for the fortunate Ninagawa.

Ikky Sjun, according to traditional sources, was born in 1394, the natural child of the Emperor Go Komatsu and a favorite lady in waiting, of the Fujiwara clan, at the Kyoto court. The Empress, seething, its told, had her banished to a low section of the city, where Ikky was born. At six the boy was sent for training to Kyotos Ankokuji Temple. Precocious, by thirteen he was composing poems in Chinese, a poem, no less, daily. At fifteen he wrote lines that were recited everywhere. He was already extremely independent, something of a gadfly.

There was much that bothered him about temple life, its pious snobbery over family connections, and he nettled fellow monks with his sharp comments. By seventeen Ikky had a Zen master, Ken, with whom he lived for four years, until Kens death. Ken was known for modesty and compassionate concern for the welfare of his disciples, and his loss affected Ikky profoundly. In comparison with Ken, other Zen masters seemed ridiculously ostentations and, in matters of temple ritual, nitpicking. Seeking another master, Ikky chose a severe disciplinarian of the Rinzai sect named Kas Sdon. He was of the Daitokuji Temple line, whose distinguished lineage led to Hakuin (16861769), among its greatest heirs.

While Kas was aware of the importance of such lineage, and performed his abbots duties faithfully, he preferred living in a small temple in Kataka, a short distance from Kyoto on the shore of Lake Biwa. When twenty-five, Ikky, hearing a song from the Heike Monogatari, suddenly penetrated a koan (Zen problem for meditation) given him by Kas, and he always was to speak of the moment as his first kensh (awakening). But a more profound experience came two years later. While meditating in a boat on Lake Biwa, hearing a crow call, he was immediately, fully enlightened. He hurried to Kas for approval of his satori, but the master said, This is the enlightenment of a mere arhat, youre no master yet. Ikky replied, Then Im happy to be an arhat, I detest masters.

At which Kas declared, Ha, now you really are a master. After his awakening Ikky stayed with the master, taking care of him in growing illness, a paralysis of the lower limbs that necessitated his being carried everywhere. Ikkys unflagging loyalty impressed all, became legendary: my dying teacher could not wipe himself unlike you disciples who use bamboo I cleaned his lovely ass with my bare hands Kas died when Ikky was thirty-five, and the bereaved monk, who at the darkest moment of mourning had been close to suicide, began an endless round of travel, lasting the remainder of his life. He could not settle anywhere, and his behavior, even in those bawdy times, was thought scandalous. He never pretended to be saintly, took his passions as a natural part of life, frankly loved sake and women. After a disappointing day he would rush from the temple to a bar, wind up at a brothel.

After which there was often a crisis of self-doubt, if not guilt. At such moments he went to his hermitage in the mountains at Joo: ten years of whorehouse joy Im alone now in the mountains the pines are like a jail the wind scratches my skin Ikky also had a hermitage in Kyoto which he called Katsuroan (Blind Donkey Hermitage), and often stayed at Daitokuji. But increasingly, to the point of anguish, he became disgusted with worldly carryings on at the main temple, shuddered at the business side of its affairs, and felt intense enmity toward Kass successor, Ys. Twenty years his senior, Ys represented all Ikky despised in Rinzai practices of the day, among them frantic hustling for donations: Ys hangs up ladles baskets useless donations in the temple my styles a straw raincoat strolls by rivers and lakes ...................................................... ten fussy days running this temple all red tape look me up if you want to in the bar whorehouse fish market In 1471, when seventy-seven, Ikky revealed his passion for a blind girl, an attendant at the Shonan Temple at Takigi. He wrote poems about their affair, some farcical, some very moving.