Table of Contents

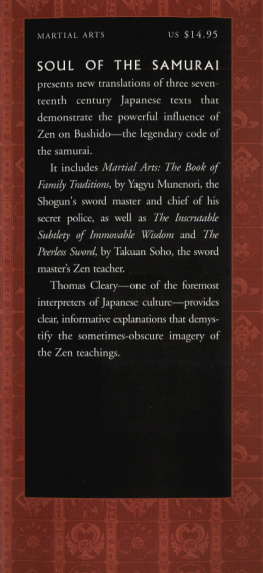

ABOUT THE BOOKThe Japanese have always closely associated the sword and the spirit, but it was in the 1600s during the Tokugawa shogunate when the techniques of swordsmanship became forever associated with the spirit of Zen. The Unfettered Mind is a book of advice on swordsmanship and the cultivation of right mind and intention, written by the 17th-century Zen master Takuan Sh (1573-1645). Takuan was a gardener, calligrapher, poet, author, adviser to samurai and shoguns, and a pivotal figure in Zen painting. He was also known for his brilliance and acerbic wit. The succinct and pointed essays in this book were written to the samurai Yagyu Munenori, who was a great swordsman and rival to the legendary Miyamoto Musashi.In these writings Soho is concerned primarily with understanding and refining the mindboth generally and when faced with conflict. Soho illuminates the difference between the right mind and the confused mind, the nature of right-mindedness, and what makes life precious. First published in 1988, this book is considered a true classic that influenced the direction that the art of Japanese swordsmanship has taken since.WILLIAM SCOTT WILSON is the foremost translator into English of traditional Japanese texts on samurai culture. His best-selling translations include Hagakure and The Book of Five Rings .Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

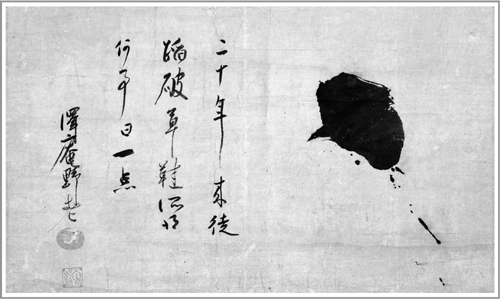

OneAfter twenty years of wearing outcountless straw sandalsWhat can you say to have gained?This one point!

Takuan Sh

The Unfettered Mind

Writings from a Zen Master to a Master Swordsman

Takuan Sh

Translated by William Scott Wilson

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2012

Frontispiece: Ichi by Takuan Sh.

Used by permission of Kaeru-An. Translation by John Stevens.

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

English translation 1986 and 2002 by William Scott Wilson

Cover art from the John Stevens Collection

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Takuan Soho, 15731645.

[Works. Selections. English. 2012]

The unfettered mind / Takuan Soho; translated by William Scott Wilson.

pagescm

eISBN 978-0-8348-2789-9

ISBN 978-1-59030-986-5 (pbk.)

1. Zen BuddhismDoctrines. 2. Martial artsReligious aspectsZen Buddhism. 3.Takuan Soho, 15731645Correspondence. 4. Zen priestsJapanCorrespondence. I. Wilson, William Scott, 1944 translator, writer of added commentary. II.Title.

BQ9399.T332 2012

294.3420427dc23

2011049235

CONTENTS

Dedicated to

Gary Miller Haskins

PUBLISHERS NOTE

This book includes some diacritics and special characters. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader device to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

The sword, which we in the West are encouraged to beat into plowshares, and the correct techniques and mentality for using it are the main topics of the three essays presented here. The essays, two of which were letters to master swordsmen, were written by a Zen monk, Takuan Sh, whose vow was the enlightenment and salvation of all sentient beings. What business a priest of Buddhism had with an instrument of destruction and advice on how to become more proficient with it is unlikely to be immediately clear to the Western reader.

The sword and the spirit have long been closely associated by the Japanese. In both history and mythology, the sword figures as an instrument of life and death, of purity and honor, of authority and even of divinity. Historically, it was possession of the iron sword that helped secure the islands for the migrants from the Asian mainland in the second and third centuries CE , the success of that conquest raising the sword to an object of ceremony as well as one of victory. Mythologically, it was the sword found within the Yamata no Orochi, a dragonlike serpent killed by the god of storms, that was to become one of the Three Imperial Regalia, symbols of power and purity revered by the Japanese for nearly two millenia. Practically, it has been the samurai class, with the sword on one side and the spiritual on the other, that has been the inspiration for many of the countrys lasting values.

This association was not dimmed by the conversion of the samurai to other occupations a little over a century ago. Even today, the infrequent forging of a new Japanese sword takes place in a highly spiritual atmosphere. The work itself is preceded by prayers to the proper divinities and the performance of purification rites, and is executed while wearing ceremonial robes without and maintaining a reverential frame of mind within. The owner of the sword is expected to respond to his good fortune in a like mentality; and, indeed, when the Japanese businessman finds a quiet moment at home to unwrap, unsheathe, and lightly powder his sword against rust, it is considered to be an exercise in meditation, not the idle admiration of a work of art.

The sword, the spiritual exercise, and the unfettered mind are the pivots upon which these essays turn. With effort and patience, the writer reminds us, they should become one. We are to practice, practice with whatever we may have at hand, until the enemies of our own anger, hesitation, and greed are cut down with the celerity and decisiveness of the stroke of a sword.

There are several editions of the works included here, but they seem to be without significant differences. I have based these translations on the texts given in Nihon no Zen Goroku, Vol. 13, which in turn uses those found in Takuan Osh Zensh published by the Takuan Osh Zensh Kank Kai.

In appreciation I would like to sincerely thank Ms. Agnes Youngblood, who helped me through parts of the translation where I had the most difficulty; John Siscoe for his encouragement and suggestions; and Prof. Jay Rubin and Teruko Chin of the University of Washington for helping me with background material over a distance of four thousand miles and a few inches of snow. Any and all mistakes are my own.

Takuan Sh was a Zen monk, calligrapher, painter, poet, gardener, tea master, and, perhaps, inventor of the pickle that even today retains his name. His writings were prodigious (the collected works fill six volumes), and are a source of guidance and inspiration to the Japanese people today, as they have been for three and a half centuries. Adviser and confidant to high and low, he seems to have moved freely through almost every stratum of society, instructing both shogun and emperor and, as legend has it, being friend and teacher to the swordsman/artist Miyamoto Musashi. He seems to have remained unaffected by his fame and popularity, and at the approach of death he instructed his disciples, Bury my body in the mountain behind the temple, cover it with dirt, and go home. Read no sutras, hold no ceremony. Receive no gifts from either monk or laity. Let the monks wear their robes, eat their meals and carry on as on normal days. At his final moment, he wrote the Chinese character for yume (dream), put down the brush, and died.

Next page

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.