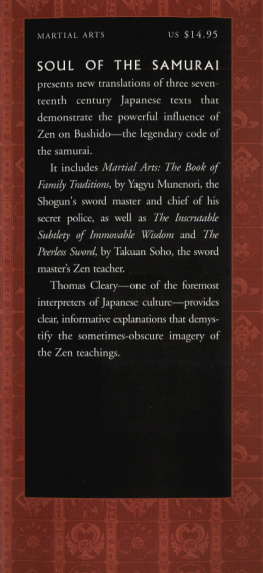

THE UNFETTERED MIND

WRITINGS OF THE ZEN MASTER TO THE SWORD MASTER

TAKUAN SOHO

(translated by William Scott Wilson)

Introduction

Takuan Soho (1573-1645) was a prelate of the Rinzai Sect of Zen, well remembered for this strength of character and acerbic wit; and he was also gardener, poet, tea master, prolific author and a pivotal figure in Zen painting and calligraphy.

It is said that Takuan sought to infuse the spirit of Zen into every aspect of life that caught his interest, such things as calligraphy, poetry, gardening and the arts in general. This he also did with the art of the sword.

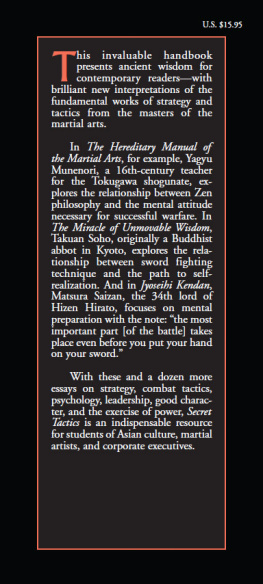

Of the three essays included in this translation, two were letters: Fudochishinmyoroku, The Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom, written to Yagyu Munenori, head of the Yagyu Shinkage school of swordsmanship and teacher to two generations of shoguns; and Taiaki, Annals of the Sword Taia, written perhaps to Munenori or possibly to Ono Tadaaki, head of the Itto school of swordsmanship and also an official instructor to the shoguns family and close retainers.

As a whole all three are addressed to the samurai class, and all three seek to unify the spirit of Zen with the spirit of the sword. Individually and broadly speaking, one could say that Fudochishinmyoroku deals not only with technique, but with how the self is related to the Self during confrontation and how an individual may become a unified whole. Taiaki on the other hand, deals more with the psychological aspects of the relationship between the self and the other. Between these, Reiroshu, The Clear Sound of Jewels, deals with the fundamental nature of the human being, with how a swordsman, daimyo or any person, for that matter can know the difference between what is right and what is mere selfishness, and can understand the basic question of knowing when and how to die.

All three essays turn the individual knowledge of himself, and hence to the art of life.

THE MYSTERIOUS RECORD OF IMMOVABLE WISDOM

The Affliction Of Abiding In Ignorance

The term ignorance means the absence of enlightenment. Which is to say, delusion.

Abiding place means the place where the mind stops.

In the practice of Buddhism, there are said to be fifty-two stages, and within these fifty-two, the place where the mind stops at one thing is called the abidingplace. Abiding signifies stopping, and stopping means the mind is being detained by some matter, which may be any matter at all.

To speak in terms of your own martial art, when you first notice the sword that is moving to strike you, if you think of meeting that sword just as it is, your mind will stop at the sword in just that position, your own movements will be undone, and you will be cut down by your opponent. This is what stopping means.

Although you see the sword that moves to strike you, if your mind is not detained by it and you meet the rhythm of the advancing sword; if you do not think of striking your opponent and no thoughts or judgments remain; if the instant you see the swinging sword your mind is not the least bit detained and you move straight in and wrench the sword away from him; the sword that was going to cut you down will become your own, and, contrarily, will be the sword that cuts down your opponent.

In Zen this is called "Grabbing the spear and, contrariwise, piercing the man who had come to pierce you." The spear is a weapon. The heart of this is that the sword you wrest from your adversary becomes the sword that cuts him down. This is what you, in your style, call "No-Sword."

Whether by the strike of the enemy or your own thrust, whether by the man who strikes or the sword that strikes, whether by position or rhythm, if your mind is diverted in any way, your actions will falter, and this can mean that you will be cut down.

If you place yourself before your opponent, your mind will be taken by him. You should not place your mind within yourself. Bracing the mind in the body is something done only at the inception of training, when one is a beginner.

The mind can be taken by the sword. If you put your mind in the rhythm of the contest, your mind can be taken by that as well. If you place your mind in your own sword, your mind can be taken by your own sword. Your mind stopping at any of these places, you become an empty shell. You surely recall such situations yourself. They can be said to apply to Buddhism.

In Buddhism, we call this stopping of the mind delusion. Thus we say, "The affliction of abiding in ignorance."

The Immovable Wisdom Of All Buddhas

Immovable means unmoving.

Wisdom means the wisdom of intelligence.

Although wisdom is called immovable, this does not signify any insentient thing, like wood or stone. It moves as the mind is wont to move: forward or back, to the left, to the right, in the ten directions and to the eight points; and the mind that does not stop at all is called immovable wisdom.

Fudo Myoo grasps a sword in his right hand and holds a rope in his left hand. He bares his teeth and his eyes flash with anger. His form stands firmly, ready to defeat the evil spirits that would obstruct the Buddhist Law. This is not hidden in any country anywhere. His form is made in the shape of a protector of Buddhism, while his embodiment is that of immovable wisdom. This is what is shown to living things.

Seeing this form, the ordinary man becomes afraid and has no thoughts of becoming an enemy of Buddhism. The man who is close to enlightenment understands that this manifests immovable wisdom and clears away all delusion. For the man who can make his immovable wisdom apparent and who is able to physically practice this mental dharma as well as Fudo Myoo, the evil spirits will no longer proliferate. This is the purpose of Fudo Myoo's tidings.

What is called Fudo Myoo is said to be one's unmoving mind and an unvacillating body. Unvacillating means not being detained by anything.

Glancing at something and not stopping the mind is called immovable. This is becausewhen the mind stops at something, as the breast is filled with various judgments, there are various movements within it. When its movements cease, the stopping mind moves, but does not move at all.

If ten men, each with a sword, come at you with swords slashing, if you parry each sword without stopping the mind at each action, and go from one to the next, you will not be lacking in a proper action for every one of the ten.

Although the mind act ten times against ten men, if it does not halt at even one of them and you react to one after another, will proper action be lacking?

But if the mind stops before one of these men, though you parry his striking sword, when the next man comes, the right action will have slipped away.

Considering that the Thousand-Armed Kannon has one thousand arms on its one body, if the mind stops at the one holding a bow, the other nine hundred and ninety-nine will be useless. It is because the mind is not detained at one place that all the arms are useful.

As for Kannon, to what purpose would it have a thousand arms attached to one body? This form is made with the intent of pointing out to men that if their immovable wisdom is let go, even if a body have a thousand arms, every one will be of use.

When facing a single tree, if you look at a single one of I its red leaves, you will not see all the others. When the eye is not set on any one leaf, and you face the tree with nothing at all in mind, any number of leaves are visible to the eye without limit. But if a single leaf holds the eye, it will be as if the remaining leaves were not there.

Next page