Copyright 2008 Shanghai Press and Publishing Development Co., Ltd.

All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction, in any manner, is prohibited.

This book is edited and designed by the Editorial Committee of Cultural China series.

Managing Directors: Wang Youbu, Xu Naiqing

Editorial Director: Wu Ying

Editors: Zhou Kexi, Yang Xiaohe, Mina Tenison

Assistant Editor: Jiang Junyan

Text by Yi Yuan, Xiong Mingxiang

Translation by Jiang Yajun, Chen Xiang

Interior and Cover Design: Yuan Yinchang, Xue Wenqing, Hu Bin

ISBN: 978-1-60220-113-2

Address any comments about The Beginners Guide to Chinese Calligraphy: An Introduction to Kaishu (Standard Script) to:

Better Link Press

99 Park Ave

New York, NY 10016

USA

or

Shanghai Press and Publishing Development Co., Ltd.

F 7 Donghu Road, Shanghai, China (200031)

Email:

Printed in China by Shenzhen Donnelley Printing Co., Ltd.

5 7 9 10 8 6 4

Contents

Preface

A s one of the most fascinating artistic forms in the world, Chinese calligraphy has long been an area of interest to both novices and researchers.

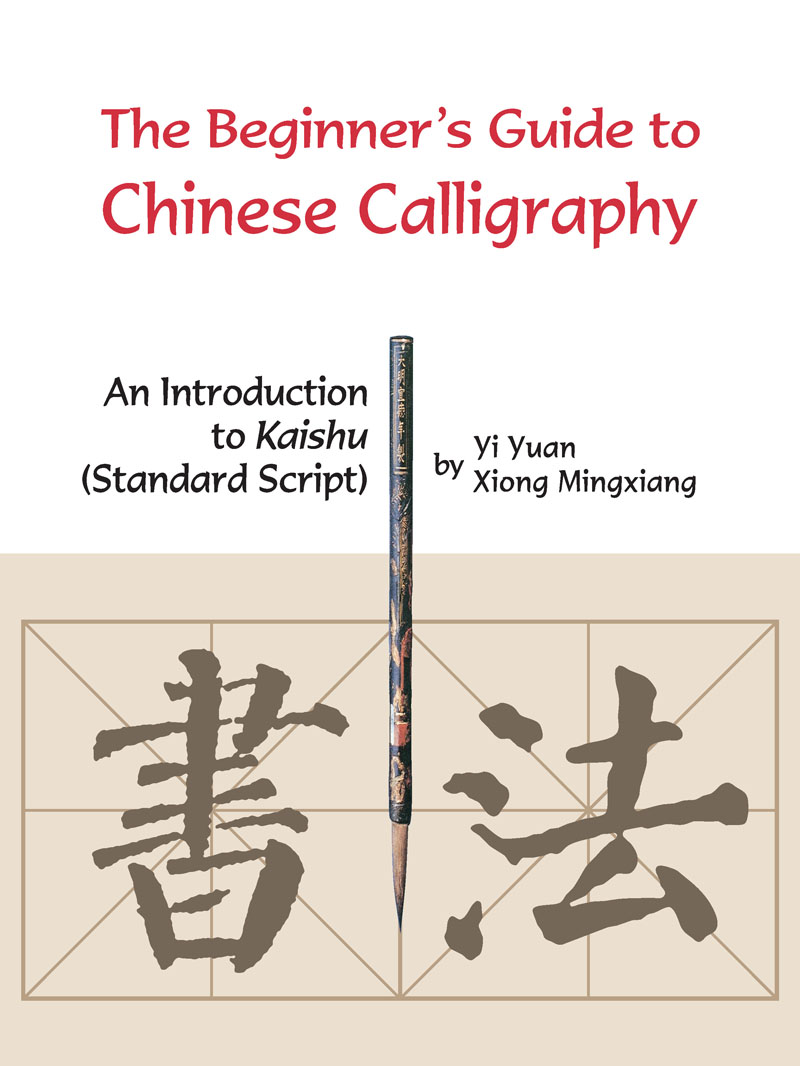

The purpose of this introductory book is two-fold. On one hand, it contains a short history of Chinese calligraphy and an introduction to Kaishu style (standard script), which embodies the very essence of the Oriental arts for those who find themselves interested in arts of East Asian countries. On the other hand, for those who know about Chinese calligraphy and want to try their hand at it, the book, with standard script as a starting point, introduces the basic skills of the ancient and exquisite art of Chinese calligraphy. The rules and methods contained in the book will make the learning process easier with clear diagrams and images.

A Brief History of Chinese Calligraphy

A s you enjoy the strokes of voluptuous beauty in the Chinese calligraphic works, focus your attention on something more than calligraphy itself, notably, the Chinese history and cultural tradition, into which the calligraphy was born and with which it has been developing as a form of art. You may wonder: where does the calligraphic beauty come from? Like any other form of art in the world, calligraphy in China owes its glory to its creator, the calligrapher, Art is life, as is believed. It was the legendary lives of the many calligraphers that gave birth to the Chinese calligraphy as the most Chinese form of art. As Liu Xizai, a renowned calligraphic critic in the Qing Dynasty (16441911), rightly observed, A calligraphic work of art mirrors life. It is the culmination of the calligraphers learning, talent, and aspiration. In a word, it becomes what the calligrapher is.

Figure 1

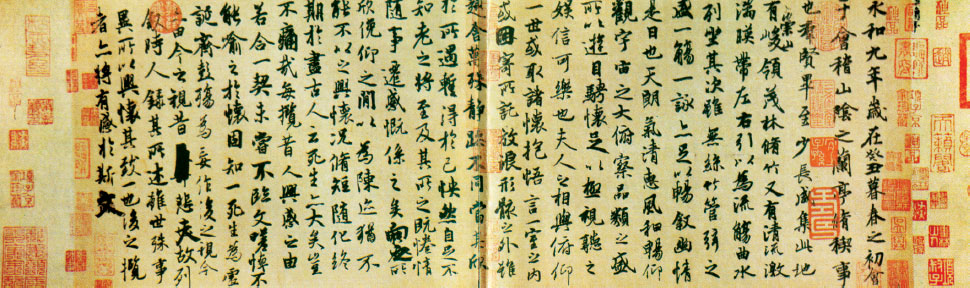

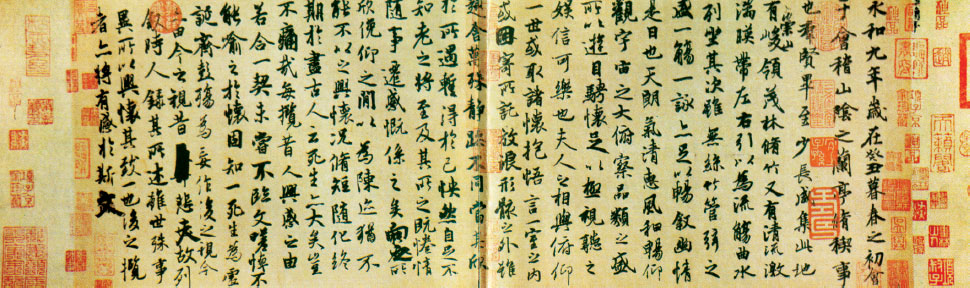

When it comes to the beauty of brush calligraphy, Wang Xizhi (303361) and Yan Zhenqing (709785) are household names in China. Stories about them have been passed from one generation to the next. Wang was a calligrapher who eclipsed all his contemporaries during the Eastern Jin period of the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420589). Acknowledged as the Sage of Calligrapher, he is often referred to as the greatest artist in the history of the field. While his authentic works are difficult to find due to passage of time, his masterpieces are still considered the highest realm a calligrapher can reach. The extant copy of his Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection (manner in which it was done: On March 3, the ninth year of Yonghe (353), Wang Xizhi, along with more than forty of others, was at the Orchid Pavilion in Shanyin (suburb of present Shaoxing city, Zhejiang Province) to celebrate the coming of spring. The gentle breeze and the shining sun must have delighted the brushes of the tipsy men of letters and, as a result, 26 pieces of poems were composed. Wang was recommended to write a preface to make an edited collection. On alcoholic strength, he finished composing and writing the 324 Chinese characters in 28 lines, in a very short time. It was said that Wang tried to better it, but in vain, leaving intact the copy of masterpiece known throughout the ages. With fine and exquisite strokes, and graceful and coherent wording, the piece is permeated with an atmosphere of the happiness and cheerfulness the calligrapher must have enjoyed. Although only a draft, the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection is the earliest model in history that calligraphers have tried to follow, not only because it pioneered the calligraphic style of freedom and elegance, but also because it upheld the tradition of art representing life.

Nearly 400 years later in the Tang Dynasty (618907), Yan Zhenqing, a statesman and calligrapher, immortalized his name in the history of Chinese calligraphy in the year of 758 with his Draft of the Eulogy for My Nephew. Different from the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection, Yans masterpiece is about a soul-stirring tragedy, an eulogy of Yan Jiming, his nephew, who, along with his father, fought against a rebellious army in the An Lushan-Shi Siming Rebellion in the years of Tianbao in the Tang Dynasty. Defeated, Yan Jiming and his father were killed. In a grievous and indignant mood, Yan Zhenqing composed the 25 lines of the poem, with a total of 234 Chinese characters, when the head of his nephew was brought to him. While the first 12 lines were written in a controlled tone of voice, the rest is permeated with the great grief of losing ones dearest, with varied touches of the brush and uneven spaces between characters and lines. In particular, the concluding part, which must have been done swiftly, gives a hint as to the magnitude of his grief. The Draft of the Eulogy for My Nephew is among the few of Chinese calligraphic works that bring out the beauty of tragedy.

The above few examples demonstrate the stories behind every single piece of calligraphy. Calligraphy is not just about the right number of strokes; it is a meditation on art as life. Treat this book like a journey to the realm of Chinese calligraphy, and it will ever delight you, and help you gain a better understanding of the art.

Beauty of Simplicity: From the Shang to the Eastern Han Dynasty (1600 BCAD 220)

The history of written script in China can be traced back to as far as 4,000 years ago, from the archeological evidence. The earliest symbols found on pottery from the prehistoric period are more pictorial, but they were no doubt the earliest written forms that Chinese ancestors used to express meaning and keep a record of events. As the society evolved, pictographs were created to express more complicated ideas, and the earliest of ). Oracle bone script are symbols inscribed into tortoise shells or ox bones with sharp tools. They are very simple both in style and technique, and pictographic in nature. In the late Yin Dynasty, as a result of the development in metallurgical techniques, people were able to produce fine vessels, and the inscriptions, called Jinwen (bronze script), were etched on them. Compared with oracle bone script, bronze script is more regular and shows more graceful lines. Bronze script was used and improved until the Spring and Autumn and Warring States (770221 BC), during which, in addition to vessel scripts, scripts on other materials were found. These included, among others,

Next page

![Zhang Gongzhe [张公者] - Contemporary Chinese Calligraphy [当代中国书法]](/uploads/posts/book/126572/thumbs/zhang-gongzhe-contemporary-chinese.jpg)