Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Chinese Script

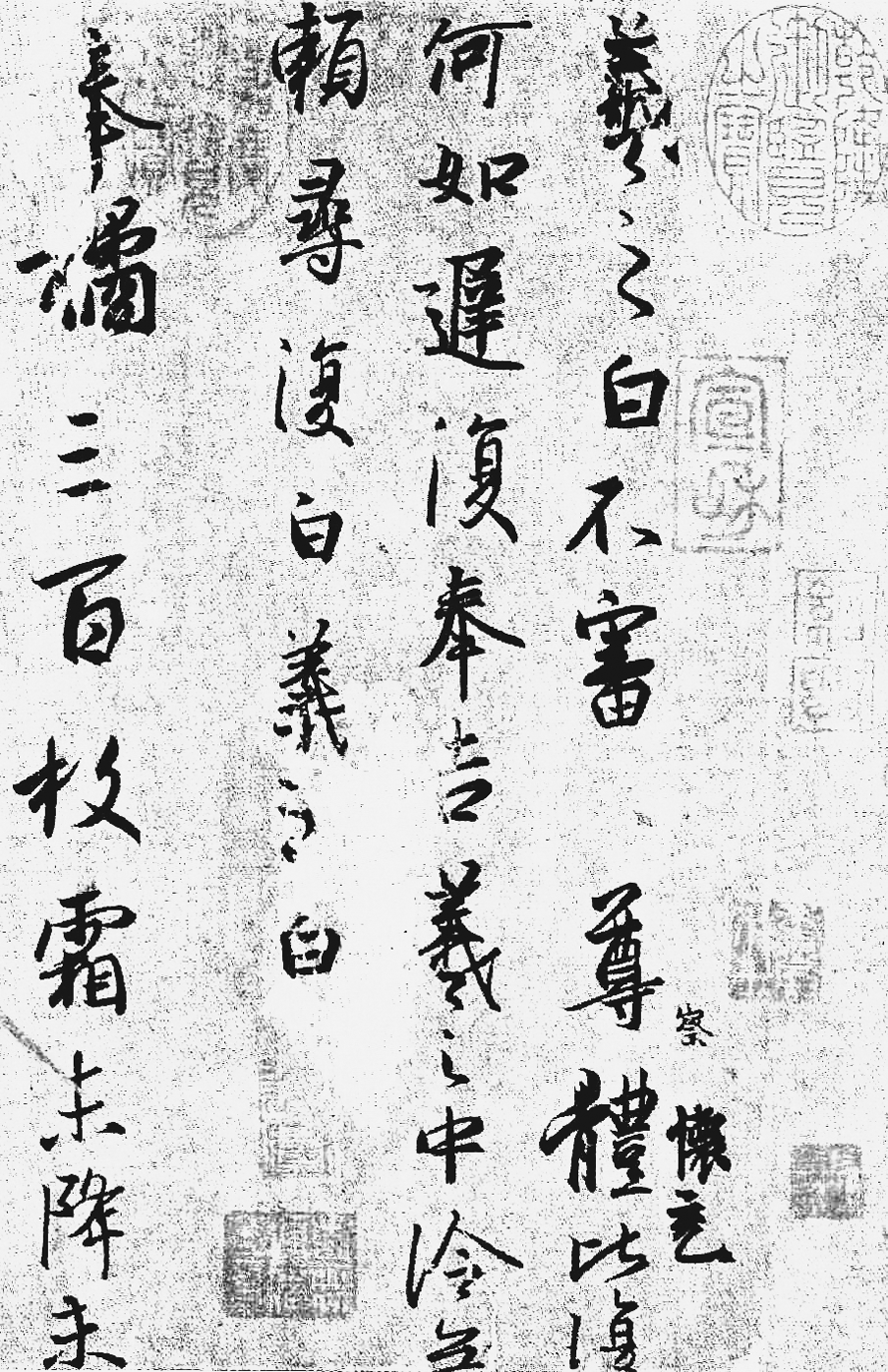

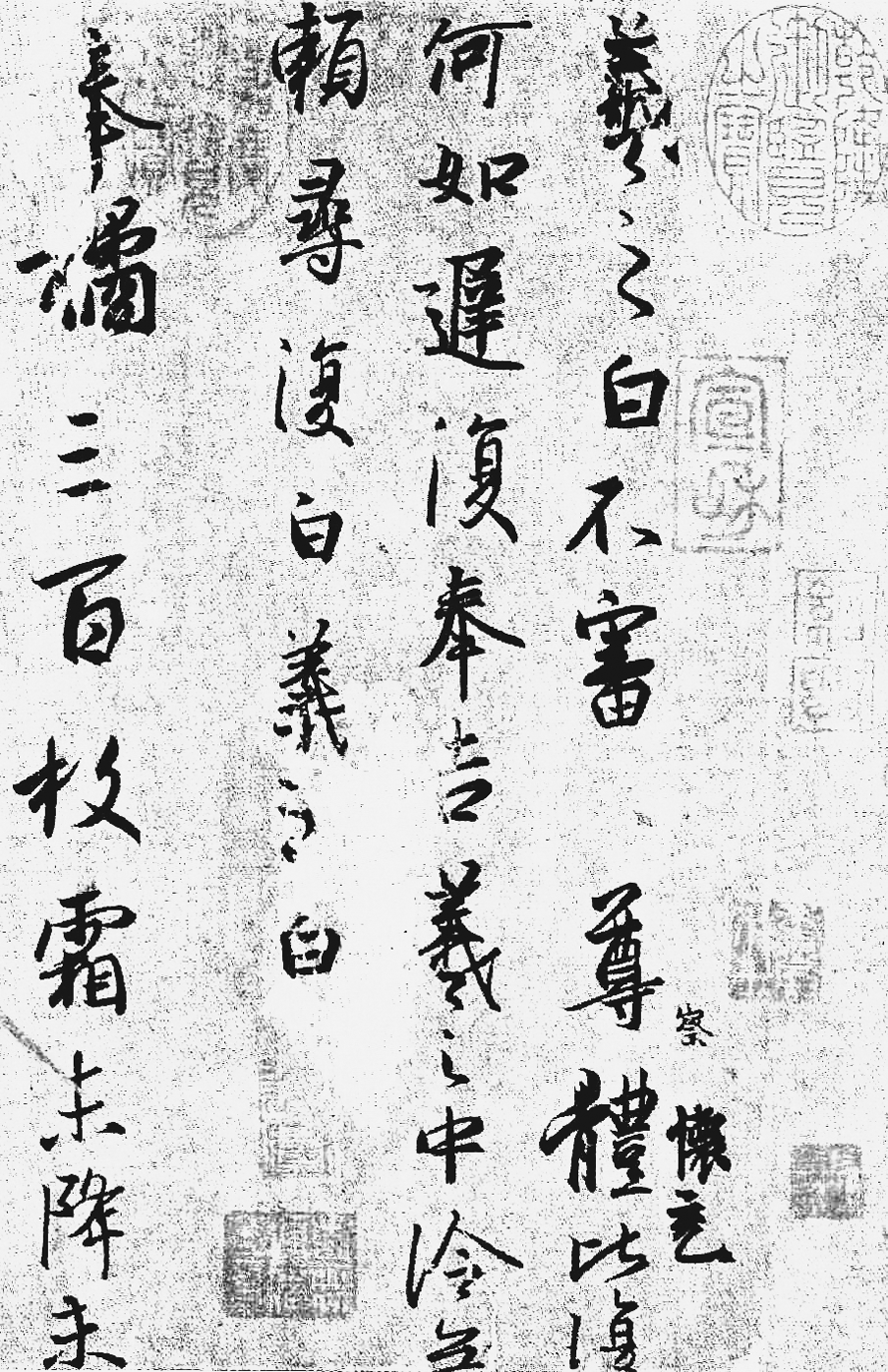

Wang Xizhi (307365), three letter extracts composed in different characteristic styles. Jiang Fucong, ed., Gugong fashu xuancui (Taibei, 1970), plate 1

CHINESE SCRIPT

History, Characters, Calligraphy

THOMAS O. HLLMANN

Translated by Maximiliane Donicht

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Originally published as Die Chinesische Schrift: Geschichte, Zeichen, Kalligraphie , Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Mnchen 2015

Translation copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54373-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hllmann, Thomas O. author. | Donicht, Maximiliane, translator.

Title: Chinese script : history, characters, calligraphy / Thomas O. Hllmann ; translated by Maximiliane Donicht.

Other titles: Chinesische Schrift. English

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017016516 (print) | LCCN 2017045266 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231181723 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231181730 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese languageWriting. | Calligraphy, Chinese.

Classification: LCC PL1171 (ebook) | LCC PL1171 .H628513 2017 (print) | DDC 495.11/1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017016516

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover image: Victoria and Albert Museum

CONTENTS

Inspiration and Drill

The Script

Ingenuity and Passion

Book Printing and Its Consequences

ImportExport

Calligraphy

The worst is that they possess neither letters nor an alphabet. They express everything by means of symbols or pictograms, which at times have two or three different meanings or even make up entire parts of a sentence. To acquire the terms and phrases paramount for the propagation of faith, and the most commonly used ones, necessary for everyday conversation, a knowledge of merely 9,000 symbols should suffice. This is how the Jesuit Johannes Grueber is quoted on two separate occasions by two illustrious men, who claimed to have led what today would be called an interview with the traveling missionary in 1665: Lorenzo Magalotti ( Relazione della China , 1677, 15) and Melchisdech Thvenot ( Voyage la Chine , 16661672, 8).

With regard to the number of symbols, the pious man from Linz presumably told a bit of a fib, since at the time even the average academic elite only knew slightly over half as many. This, by the way, corresponds quite accurately to the number of characters (just under 4,500) that today, three and a half centuries later, university students of the Peoples Republic of China are required to know in their first semester.

This is a tremendous challenge, and Gruebers lament will be echoed from time to time by not only prospective Sinologists but also the countless Western laymen trying to acquire a more or less thorough understanding of Chinese, not least out of respect for Chinese culture, of which the written language is a constitutive component: as a medium of communication, as an artistic mode of expression, and as a chief element in the display of national identity.

The author too faces a great challenge: on the one hand, he may not upset the already knowledgeable reader with an at times necessary reduction in complexity; on the other hand, he should not discourage the layman with too great a focus on detail and technical jargon. He is also barred from fleeing into footnotes, in which he could elucidate the strengths and weaknesses of a given hypothesis.

There are different ways to approach the Chinese script. So when a primarily historical approach was chosen for this modest edition, it was not out of disrespect for other disciplines but simply on the grounds of limited competence. Due to the predetermined length of the book, even within this historical framework, several topics could only be touched upon superficially, such as the politics of script, book printing, and calligraphyall of which would certainly warrant their own monographs.

The Chinese characters in the text serve to illustrate the arguments brought forth, not to lend it exotic flair or the pretense of scientificness. Except in the sections that deal explicitly with simplified characters, traditional characters were given preference throughout, not only because of their disparately longer tradition but alsoand especiallydue to their greater clarity. Transliteration consistently follows the rules of the Pinyin transcription system. Lastly, emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties are referred to using their far more commonly known era names instead of their (technically correct) posthumous names. The author translated all quotes and excerpts into German himself, and his translations were used as the basis for the English version of this book, except for quotes or excerpts originally in English.

The making of this book was accompanied by Ulrich Nolte, Petra Rehder, Gisela Muhn, and Bettina Seng on the part of the German publisher; Johannes Bahle, Werner Berthel, Claudia Burgert, Cai Jiehua, Rebecca Ehrenwirth, Waltraud Gerstendrfer, Sabine Hllmann, Anette Liersch, Markus Michalek, Shing Mller, Marc Nrnberger, Luise Punge, Dennis Schilling, Renate Stephan, and Christine Zeile contributed countless pieces of advice to improve its lucidity. I owe them all my sincerest thanks. Incidentally, what Zhu Fu wrote in a letter to Peng Chong in the year 26 is valid: In everything you do, avoid causing those closest to you pain, and those hostile to you joy ( Wenxuan , 521, ch. 41).

Youll see them in parks in the big cities: small groups of men and women carrying buckets of water, into which they dip giant brushesin a pinch, mopswith which they proceed to write characters on the pavement, large enough so that they can be read even from a distance. This is often followed by passionate discussions about the calligraphies aesthetic qualities. But the discussions never last long, for neither do their subjects; the water dries quickly, and from the moment of its creation, every piece carries within it the seed of impermanence. In other contexts too, script is a popular topic of conversation in China. It has great cohesive force and is perhaps the most visible symbol of national identity. But there are also entirely practical reasons the Latin alphabet never stood a realistic chance of being adopted, and almost every program on television is subtitled.

Many Languages, One Script

Even though China strives to give the impression of cultural homogeneity and consistency, to this day the coexistence of its regional traditions plays a role almost as important as its governmentally decreed unity. The same is true of its linguistic diversity: not only with respect to ethnic minorities, who, for instance, converse in Uyghur, Mongolian, or Tibetan, but also regarding the Han, who make up 91.5 percent and therefore the majority of the countrys population. There are plenty of good reasons to summarize all of Chinas commonly used (Sinitic) languages under the umbrella term Chinese. Yet this choice of terminology communicatesintentionally or unintentionallya closedness that cannot be wholly reconciled with Chinas everyday reality.