The Land of the Five Flavors

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

The Land of the Five Flavors

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF CHINESE CUISINE

Thomas O. Hllmann

Translated by Karen Margolis

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2010 Verlag C. H. Beck oHG, Munich

Translation copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-2-231-53654-7

Support for this translation was funded in part by Breuninger Foundation and the Department of Asian Studies, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hllmann, Thomas O.

[Schlafender Lotos, trunkenes Huhn. English]

The land of the five flavors : a cultural history of chinese cuisine / Thomas O. Hllmann; translated by Karen Margolis.

pages cm. (Arts and traditions of the table. Perspectives on culinary history)

German subtitle: Kulturgeschichte der chinesischen Kche

Text in English, translated from German.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16186-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53654-7 (ebook)

1. Cooking, Chinese. 2. ChinaSocial life and customs. I. Title. II. Title: Kulturgeschichte der chinesischen Kche. III. Title: Cultural history of chinese cuisine.

TX724.5.C5H64713 2013

641.5951dc23

2013016126

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER IMAGE: Marriage Feast, nineteenth-century Chinese painting. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Eileen Tweedy/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

COVER DESIGN: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

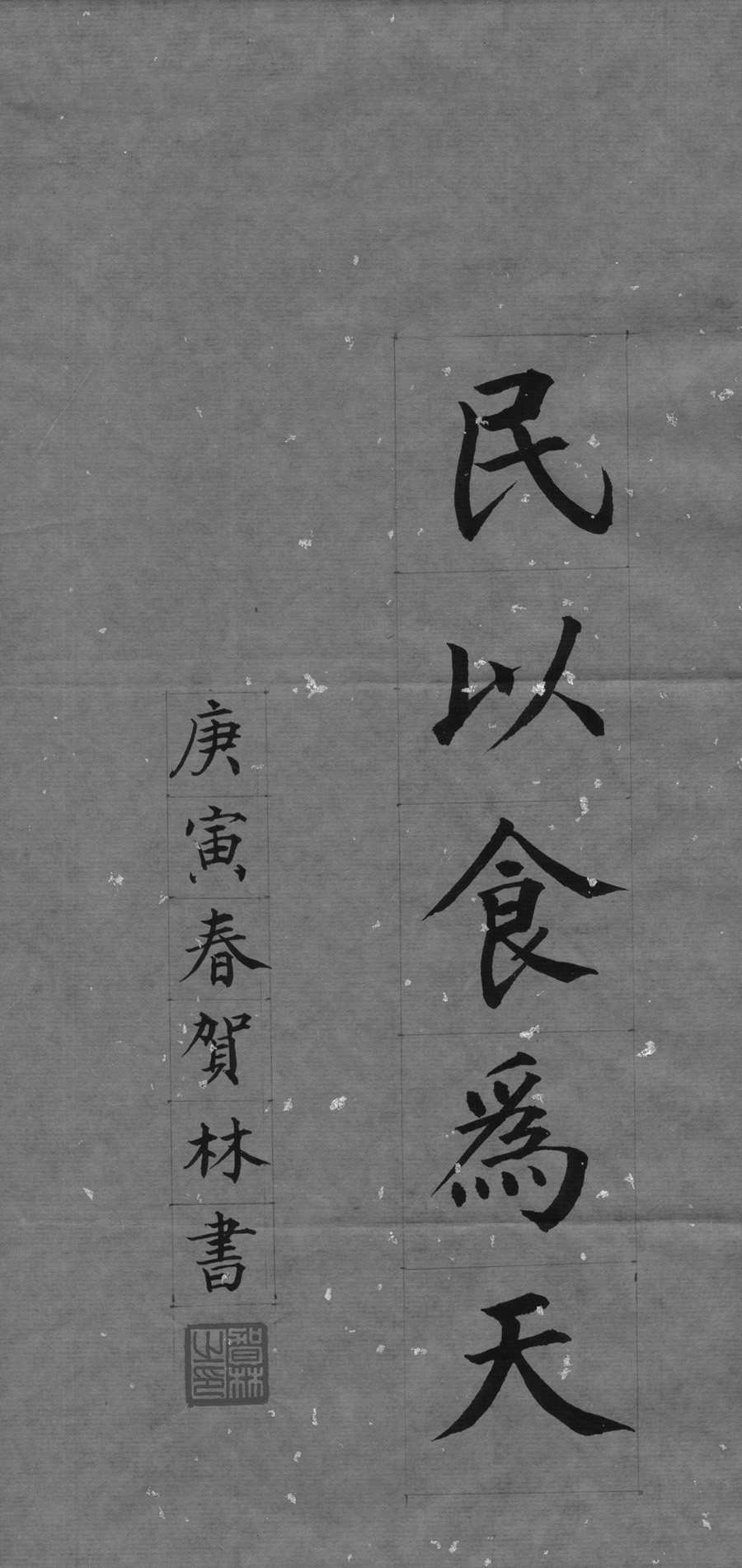

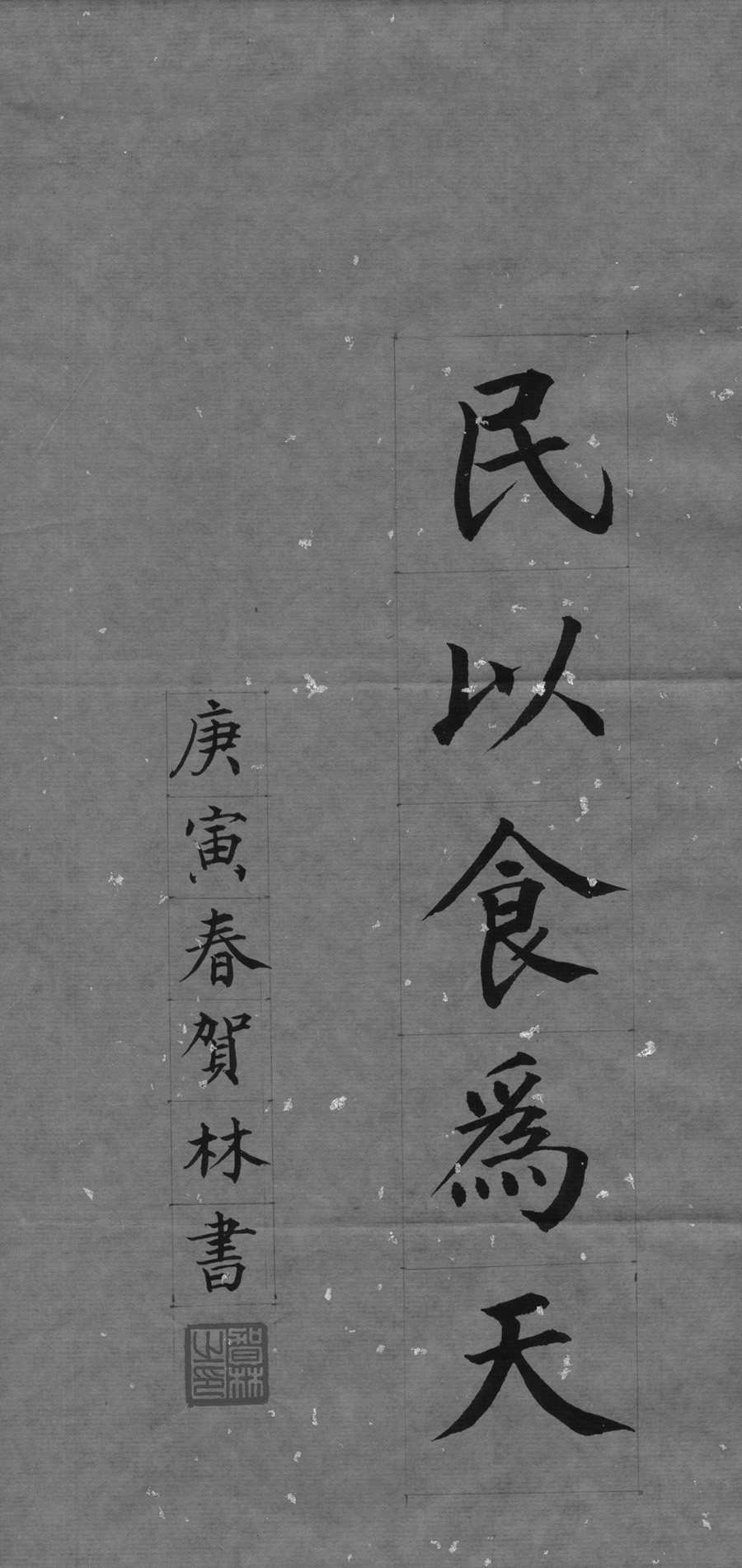

FRONTISPIECE: Calligraphy by He Lin (2010)

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

To the people, food is heaven. This is the meaning of the calligraphy by He Lin that forms the frontispiece of this book. The proverb originates from a historical work compiled in the second century (Hanshu, chapter 43). Today it is usually associated with epicurean pleasure, but this is not exactly what the saying originally meant. The heaven referred to here was not seen as a kind of ideal paradise but as a supreme force. In other words, for the majority of people living in China at that time, nothing was more important than having enough to eat.

A serious history of food culture should offer more than a chronicle of epicurean indulgence and should go beyond examining the social framework of nutrition. It should focus both on extravagance and the impact of hunger and austerity. It should also retrace traditions dating back several thousand years and indicate trends that have only recently come to light.

From a long-term perspective it seems quite clear that at least until the globalization thrust that swept China around the dawn of the third millennium, continuity was stronger than change. I have therefore chosen to explore the different topics systematically instead of using a chronological structure; I have given examples rather than following a continuous narrative thread; and I have tried to tell stories rather than simply presenting facts.

I hope this book succeeds in showing how the paradigm of nutrition in China opens a window on wider historical relationships and offers an attractive approach to Chinese history for readers who may have had little interest in East Asia so far. Thataside from the joy of cooking and spinning talesis what really motivated me to explore this theme.

Many things that seem broadly homogenous reveal surprising regional and social differences on closer inspection. Nonetheless, generalizations can sometimes be legitimate. Ultimately, there are always some kinds of exceptions, and it would make no sense to focus on every anomaly.

This book includes recipes to give readers a genuine flavor of Chinese cooking, but it is not designed as a cookbook. Keeping the balance between authenticity and feasibility requires all kinds of compromises. Whereas beginners may sometimes feel overwhelmed, experienced cooks will find some of the instructions superfluous and may frown on certain simplifications. It is difficult to avoid concessions, even in the choice of terms. To give just one example, rice wine is repeatedly mentioned as an ingredient, although from a scientific perspective it is clearly a type of beer because it is a grain product. But correct terminology is one thing, and successful shopping quite another.

China is a culinary cosmos that requires a classifying structure. For around the past two thousand years, the five flavors (sour, bitter, sweet, pungent, and salty) have been accepted as a general framework. This classification derives from the five phases (wood, fire, earth, metal, water), a schema that may seem quite rigid but that actually bears far more relation to reality than similar ancient notions such as the five points of the compass or the five seasons.

Over the centuries the culinary arts and banqueting have given rise to a rich literary tradition. To convey something of the atmosphere of these writings I have interspersed the narrative with citations, mostly originating from primary Chinese sources. Readers looking for further inspiration will surely find something to their taste in the comprehensive bibliography. I can also recommend a delightful cinematic variation on the theme: Eat Drink Man Woman (Yin shi nan n), a tender, ironic movie by Taiwanese director Ang Lee that counterpoints a story of family quarrels with exquisite scenes of culinary brilliance.

Many people have contributed to producing this book. I would particularly like to thank Chen Ganglin, Oliver Dauberschmidt, Rebecca Ehrenwirth, Waltraud Gerstendrfer, Sabine Hllmann, Shung Mller, Marc Nrnberger, Armin Selbitschka, Armin Sorge, Sandra Sukrow, and Christiane Tholen for reading the manuscript critically; Christiane Zeile and Heiko Hortsch from the publisher C.H. Beck, who were responsible for the original German edition; Jiang Bo, Hans van Ess, Jasmin Fll, Jin Tao, Bruno Richtsfeld, and Zhu Qingsheng for their valuable suggestions; and He Lin for the calligraphy. For this English language edition I would like to express my gratitude to the editor, Jennifer Crewe, and her team at Columbia University Press, and especially to Karen Margolis for her excellent translation.

Translators note: I would like to thank Caroline Bynum and Karine Chemla for their invaluable help and advice in preparing this edition.

Prestige and Consumption

If there is anything we [the Chinese] are serious about, it is not religion or learning, but food. In the 1930s, the Chinese writer Lin Yutang summed up the culinary aspirations of his fellow countrymen and women as a common denominator in his book My Country and My People (p. 337). He may have exaggerated, but a cultivated approach to food certainly plays a bigger role as a constitutive element of culture in China than in other parts of the world. It is probably no coincidence that some important statesmen in antiquity are said to have started out as butchers or cooks. Then again, mastery of the culinary profession could be risky, and some chefs ended up being obliged to accompany their lords to the graveto be buried along with the well-stocked pantry.

Of course, the degree of hedonism varied through the ages. Although there were times when corpulence could be interpreted as a sign of social status, in other periods austerity was definitely indicated. Women, above all, were subject to the dictates of fashion. The transformation in the ideal of beauty under the Tang dynasty, which occurred in two successive stages, is particularly striking. Tight-fitting garments accentuated the desirable slim figure of the early period, whereas a full figure and loose robes were fashionable in the late period. This is usually explained with reference to Yang Guifei (719756), a buxom concubine of the emperors, but clay sculptures excavated from graves show that this development must have begun much earlier.

Next page