Special thanks go to my longtime editor at Shambhala, Beth Frankl, and assistant editor Emily Coughlin. Wonder-worker design director Lora Zorian, who has also worked with me for many years, deserves special praise for her great efforts on this challenging project.

I am grateful to the many friends who provided me with photos of the treasured pieces in their collections (in alphabetical order): Richard Bowles; Eamonn Devlin; Christopher Forman; Beth Frankl; Alexander M. Greene; Gordon M. Greene; Felix Hess; Swami Ishwaranda; Ben Johnston; Andy Kay; Christine Kilian; Kenneth Kushner; Robert Matsueda; Albert Mercado; Joshua Michaell; Naej Collection; Wolf Nickel; Robert Noha; Milard Roper; Junichi Tokeshi, MD; and Leslie Wright.

INTRODUCTION

In my lifelong spiritual quest , I have read hundreds of sutras; plowed through pages and pages of philosophical texts; grappled with koan collections; analyzed thousands of poems; searched through biographies; meditated for hours; and interacted with many teachers, good and bad. However, I have gained the most from the contemplation, appreciation, and inspiration of the ink tracings of the great masters.

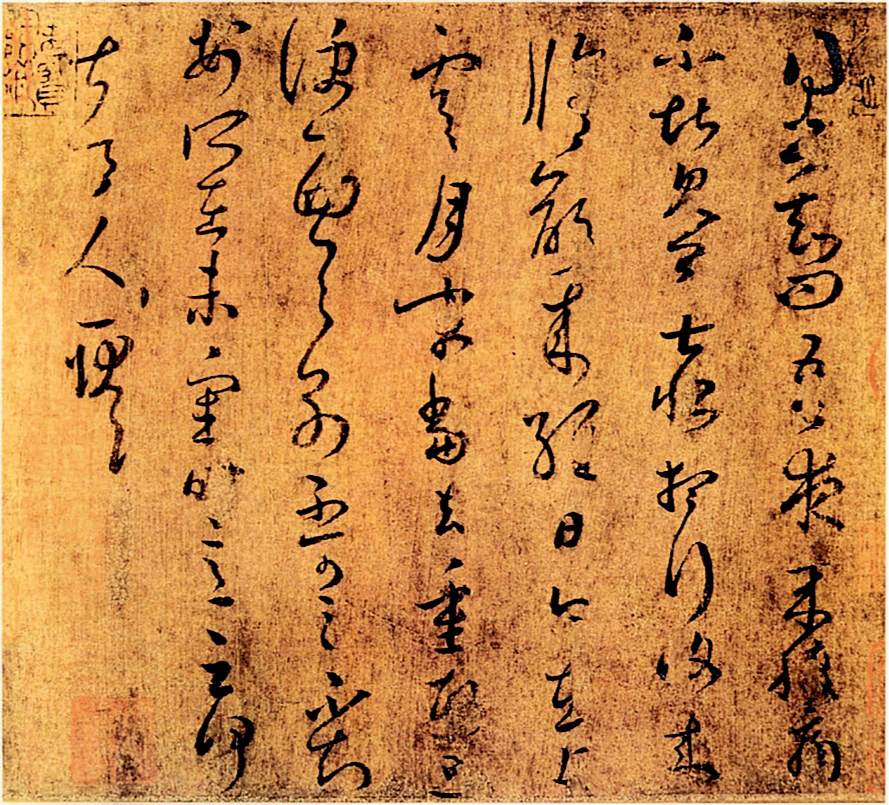

In East Asian culture, brushwork is considered a mind seala single stroke can reveal what is in a persons heart. It can also express the essence of a masters teaching. Since it is not the formation of the characters but the spirit behind the composition that matters, few of the most esteemed examples of brushwork were by professionalsand many masterpieces were by martial artists. In fact, Wang Xizhi, venerated as the greatest calligrapher in Chinese history, was a Tang dynasty general.

Portion of a facsimile of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi.

This book focuses on the brushwork of the budo masters of Japan. What defines a budo master? It refers to one who is well accomplished in all the technical aspects of the martial arts and, more importantly, the strategy behind warriorship. Strategy involves the ability to correctly evaluate an opponents strengths and weaknesses, both material and psychological. However, one can qualify as a budo master even if one never wielded a weapon or stepped on a battlefield. Although masters such as Takuan, Hakuin, and Sengai never touched a weapon as part of their Buddhist vows, they were as skilled as the best martial artists. Despite being frequently attacked by highwaymen, rogue samurai, irate daimyo insulted by criticism of their behavior, and a host of other miscreants, the masters emerged unscathed by getting out of the way, literally and figuratively.

In the fifteenth-century koan collection Shonankattoroku (no. 69), there is this example: When her husband was killed in battle, Sawa became a nun to pray for her departed loved one. She shaved her head and entered Tokei-ji (the temple in Kamakura reserved for widows and divorcees), taking the name Shotaku. She devoted herself to Zen practice for many years, eventually being appointed abbess of Tokei-ji. One evening on the way back from a regular interview with her master at Engaku-ji, she was accosted by a would-be rapist. When the attacker threatened her with a sword, she immediately pulled out a sheet of paper from her sleeve, rolled it up like a sword, and thrust it directly at his eyes. He was unable to strike back, mesmerized by her intense energy. When he turned to run, she shouted a Katsu! so powerful it knocked him over. She then whacked him on the head with the paper sword. He got up and fled in terror.

Another example: Zen Master Shoju was well known for thrashing arrogant swordsmen. One day, a pompous samurai visited Shoju and grandiosely expounded his theories on the art of the sword. Shoju listened politely for a while but then suddenly leaped up and pummeled the samurai unmercifully, exclaiming, You are full of nothing but hot air!

Word of Shojus startling behavior created a stir among the proud samurai swordsmen. They doubted that Shoju could better any of them without the element of surprise. A group of confident swordsmen was assembled. Shoju challenged them to strike, and not one could land a blow; on the contrary, Shoju delivered a counterblow with his short wooden scepter, giving each one a sharp rap on the head. Thoroughly humbled, they asked him for his secret. If your mind is free of deluded thoughts, nothing will disturb you, not even a sword attack, he replied.

While many budo masters were heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, others were notthey drew on their experiences with esoteric Buddhism, Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, folk religion, and other traditions. Like Zen, the most effective budo teachings are short and to the point. Due to the compact mediuma single sheet of paperthe essence of a masters teaching is limited to a few characters; typically a one- or two-line phrase or often only a single one-word barrier. Many budo masters painted as well. Although a few were excellent artists, the majority of their paintings are simply composed, and some are more like cartoons, often graced by a laugh-out-loud humor.

This book begins with two pieces, a painting and a calligraphy, by Miyamoto Musashi dating from the seventeenth century. Then there are a number of outstanding examples by Takuan, teacher of the Tokugawa shoguns and the Yagyu swordsmen. For the rest of the Edo period, budo masters produced calligraphy and paintings on a modest scale; not a lot of examples remain. However, beginning with Motsugai, who lived at the end of the Edo period, there was an explosion of calligraphy and painting by budo masters as a teaching vehicle and to raise money to fund various charitable causes.

Nearly all the main players involved in the Meiji Restoration had forged their spirit through budo training, initially on the battlefield and then on a more constructive level, and took a nonlethal approach to building the character of the nations new citizens. There was a regression to the old bloodthirsty military tactics during the fascist period from 1920 to 1945. Not surprisingly, the brushwork produced in this period was bombastic, overwrought, and, ironically, weak. Virtually no first-rate pieces were created. However, in the aftermath of war, the concept of budo as a way of peace emerged, promoted by Kano Jigoro, the founder of judo; Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of aikido; the philosopher activist Nakamura Tempu; and such swordsmen as Nakayama Hakudo. The emphasis was not on victory but liberation; a contest was meant to develop ones own character as well as assisting ones partner in developing his or her own. The ideal was acting in harmony, we reach the goal together.