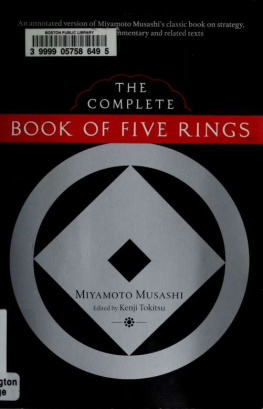

ABOUT THE BOOK

Miyamoto Musashi, who lived in Japan in the fifteenth century, was a renowned samurai warrior. He has become a martial arts icon, known not just as an undefeated dueler, but also as a master of battlefield strategy. Kenji Tokitsu turns a critical eye on Musashis life and writings, separating fact from fiction, and giving a clear picture of the man behind the myth.

Musashis best-known work, The Book of Five Rings, provides timeless insight into the nature of conflict. Tokitsu translates and provides extensive commentary on that popular work, as well as three other short texts on strategy that were written before it, and a longer, later work entitled The Way to Be Followed Alone. Tokitsu is a thoughtful and informed guide, putting the historical and philosophical aspects of the text into context, and illuminating the etymological nuances of particular Japanese words and phrases. As a modern martial artist and a scholar, Tokitsu provides a view of Musashis life and ideas that is accessible and relevant to todays readers and martial arts students.

KENJI TOKITSU was born in Japan and began studying martial arts when he was a child. He has taught karate in Paris since 1971. In 1984 he founded the Shaolin-mon school, where he teaches a synthesis of the original combat arts of Japan and China. In 2001 he established the Tokitsuryu Academy to teach and promote his method. For more information, visit www.tokitsu.com. Tokitsu also holds doctorates in sociology and in Japanese language and civilization. He is the author of numerous books.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Weatherhill

An imprint of

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

Cover art: Miyamoto Musachi, Late in Life, a self-portrait.

Courtesy of Shimada Museum of Art, 4528 Shimazaki, Kumamoto, Japan.

Cover design: Jonathan Sainsbury

Originally published as Miyamoto Musashi: Matre de Sabre japonais du XVIIe sicle ditions Dsiris, 2000

English translation 2004 by Shambhala Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tokitsu, Kenji, 1947

Miyamoto Musashi: his life and writings/Kenji Tokitsu;

translated by Sherab Chdzin Kohn.1st Weatherhill ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: Boston: Shambhala, 2004.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2488-1

ISBN 978-0-8348-0567-5 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Miyamoto, Musashi, 15841645 2. SwordsmenJapanBiography. I. Chdzin, Sherab. II. Title.

DS872.M53T65 2005

952.025092DC22

2005009839

CONTENTS

A LEGENDARY FIGURE

IN POPULAR JAPANESE CULTURE, Miyamoto Musashi is a legendary figure. This warrior of the seventeenth century, a master of the sword but also a painter, sculptor, and calligrapher, left us a body of written work that has an important place in the history of the Japanese sword. His dense and brief Gorin no sho, or Writings on the Five Elements, popularly known as The Book of Five Rings, is a summary of the art of the sword and a treatise on strategy.

Although the painting, sculpture, and calligraphy of Musashi are less well known, they are considered by connoisseurs to be of the first order.

Because of the extension of his art into so many domains and the way in which he explored the limits of the knowledge of his time, Miyamoto Musashi reminds us of Leonardo da Vinci. His personality and his adventurous life have been popularized by a famous novel and many films.

Here I present a completely new and annotated translation of the principal work of Miyamoto Musashi, as well as extensive excerpts from his other works. Because of its concision, the Gorin no sho is a hard text for contemporary Japanese people to understand. The misunderstandings can only be greater for Westerners, who might draw the impression from the apparent clarity of the text that they are understanding it when in fact the authors essential ideas are eluding them. For this reason I have accompanied the text with clarifications, some of which are historic, others linguistic, and still others related to the nature of martial arts practice. I undertook this project even though several translations of the Gorin no sho already exist. Through carefully rereading the Japanese text, I discovered that these translations contained many errors or misunderstandings.

Translation of this work is a difficult undertaking because of the considerable evolution the Japanese language has undergone since Musashis time, but even more so because of the major problem connected with the roleat once limited and importantplayed by verbal explanation in the traditional martial arts. That which is expressed in words is a little like the knot in an obi: only the knot is manifest, visible, but without the continuity of the belt, the whole thing would not hold together. What takes on meaning in the nodal point of the word is the entirety of a shared experience.

The principal mode of transmission of the martial arts was direct teaching. Words played a small role, and writing was confined for the most part to a simple enumeration of technical terms. This approach did not stem from respect for tradition; rather, it was connected with the very considerable difficulty of communicating techniques of the body and mind in writing. In the Scroll of Water, the second section of the Gorin no sho, for example, when Musashi explains techniques in words, it is difficult to understand, since the execution of each technique takes only a few seconds. The description in writing of a movement of the body that lasts only a few seconds is very complexI continually have this experience in my own work. Nevertheless, at certain moments in the course of a students development, a single word can trigger a profound understanding of the art by creating a new order for the experiences accumulated in the silence of physical practice. Musashis words have this objective.

One of the big obstacles in translating the work of Musashi lies in this gap between his words and his body. I have attempted to bridge this gap through my own experience of budo, for the Gorin no sho is one of the books that serve me as a guide in the practice of the way of martial arts. The name and image of Musashi have been familiar to me from earliest childhood through stories, films, and, later, novels.

Musashi reappeared for me in the form of the Gorin no sho at a time when, after several years of practicing karate, I began to wonder about the relationship between this art and the tradition of the sword, which I saw as the essence of budo. It should be noted that from the cultural and ideological point of view, the tradition of karate is different in some respects from that of budo. Karate was a local practice transmitted secretly on the island of Okinawa (in the extreme south of Japan), and it was not included in the framework of budo until around 1930. The degree of technical refinement and depth that had been reached by karate at that time was nowhere near that of the Japanese art of the sword. Nonetheless, it quickly emerged, after the presentation of karate to the Japanese public, that this art fit in well with the modern life of the twentieth century and was capable of developing as a contemporary form of

Next page