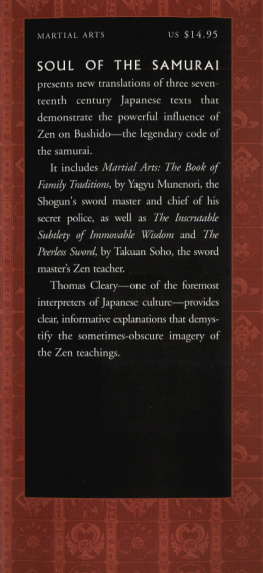

ABOUT THE BOOK

This version of the Tao Te Ching presents the classic in a unique light, through the eyes of a renowned master of the Rinzai Zen tradition. Takuan Soho, who lived from 1573 to 1645, was an acerbic, witty, free spirit; a painter, poet, author, calligrapher, gardener, and a tea master. He was also a confidant and teacher to shoguns and many other powerful and famous figures, among them the famed swordsman Yagyu Munenori, and (according to legend) Miyamoto Musashi.

True to the teachings of the Tao Te Ching itself, as well as to the tradition of Zen, Takuan draws from everyday experience and common sense, to reveal the basic sanity of nature and the inherent wholeness of life. Takuan reveals how the Tao Te Ching applies to a wide range of concerns, including health, personal relationships, and individual lifestyle. He interprets the text through a philosophical and psychological lens, and also elucidates its radical social and political concepts.

THOMAS CLEARY holds a PhD in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University and a JD from the University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. He is the translator of over fifty volumes of Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and Islamic texts from Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Pali, and Arabic.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

TAO TE CHING

Zen Teachings on the Taoist Classic

LAO-TZU AND TAKUAN SH

TRANSLATED FROM

CHINESE AND JAPANESE BY

THOMAS CLEARY

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2010

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2010 by Thomas Cleary

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Laozi.

[Dao de jing. English]

Tao Te Ching: Zen teachings on the Taoist classic / Lao-tzu and Takuan Soho; translated from Chinese and Japanese by Thomas Cleary.1st ed.

p. cm.

English translation of Dao de jing and of Takuan Sohos Japanese commentary on it.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2737-0

ISBN 978-1-59030-896-7

I. Takuan Soho, 15731645. II. Cleary, Thomas F., 1949 III. Title. IV.

Title: Zen teachings on the Taoist classic.

BL1900.L26E5 2010C 299.51482dc22 2010036651

THE TAO TE CHING (Daodejing) is one of the oldest and most beloved books in the world. Compiled in China more than two thousand years ago, during an era marked by militarism and despotism, the Tao Te Ching proposes a serene and unaffected way of life.

Thousands of commentaries have been written on the Tao Te Ching, the earliest known dating back as far as the third century B.C.E. These vary widely and touch upon virtually every aspect of human experience.

This translation of the Tao Te Ching presents the classic in a unique light, through the eyes of an authentic Zen master, the famed National Teacher Takuan Sh, who lived from 1573 to 1645.

Takuan began the practice of Pure Land Buddhism at the age of ten, and then took up Zen when he was fifteen. After attaining Zen enlightenment, he was made assistant teacher at Daitokuji, one of the most prestigious monastic centers in Japan. When he was later appointed abbot, however, he resigned after three days.

Takuan is noted for having refused invitations of powerful warlords, and was banished for protesting government regulation of religion. He eventually accepted the request of the emperor to teach, nonetheless, and also instructed the shogun.

Takuan lived in a time of transition in Japan, from a history of endemic warfare to a state of peace that was to endure for more than two centuries. He often emphasizes minimalism in government, especially in matters of warfare and taxation. This reflects the concerns of his own time, but these also paralleled the problems of war-torn Chinese society in the original historical context of the Tao Te Ching. Its relevance in this respect today need hardly be emphasized.

Takuans explanation of the Tao Te Ching interprets the philosophical and psychological meanings of the ancient text as well as its radical social and political concepts. He illustrates applications of the maxims in a wide range of connections, including health, personal relationships, and individual lifestyle. True to the teachings of the Tao Te Ching itself, as well as to the tradition of Zen, Takuan enlightens in simple, down-to-earth terms, drawing on the fabric of everyday experience, and the wellspring of common sense, to reveal the basic sanity of Nature and the inherent wholeness of life.

[1]

A way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way;

A name that can be named is not a constant name.

There were no names in the beginning of heaven and earth;

Attribution of names is the matrix of myriad things.

Whenever you have no desire, you can observe the subtle;

Whenever you have desire, watch the openings.

These two have the same provenance but different names;

Both are called mysteries.

The mystery of mysteries is called the gateway to myriad subtleties.

TAKUANS COMMENTARY

Lao-tzus book is not like reading ordinary books; one should not get so caught up and bogged down in literal meanings. In some places, this book presents analogies derived right from Lao-tzus basic intent. In some places it starts from analogy and works its way to the basic intent. So there is something difficult to grasp about what he is saying, like a dream, like a shadow. Just when you think youve found the basic idea, its a metaphor; and when you think its a metaphor, its the basic idea. Even so, this in itself is Lao-tzus basic intent, his way of proceeding. This is because his basic intent is emptiness. When you read with this in mind, you should be able to understand. Otherwise, you cant.

To sum up Lao-tzus approach, insofar as the world is as it appears, the Way too is as it appears. Thus it is not something to which people might contrive to attach various conceptions, judging this right and this wrong. In other words, the Way is as is.

A way that can be spoken means whatever can be called a way. The eternal Way is like saying the true Way. The true Way is the real Way that never changes throughout eternity. That is why it is called eternal. So if you say that the Way is just such-and-so, that is not the real Way. This is the fundamental meaning.

A name that can be named is a simile. This line is not about entry into the Way; what is said here is a simile. The idea is that the fact that A way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way is like the fact that A name that can be named is not a constant name. Because you think this line expounds the Way, no matter what you say, it is insufficient; but when you see it as a simile in this way, that will be effective.

A name that can be named is like calling water water. If it had always been called fire, wed call it fire. So it is also with fire. The same thing, water, is called shui in Chinese, while in Japan its called mizu in the capital, but people of the western provinces say minzu. Thats the way it issince names are all assigned by human beings, they can be changed at will, even now. To say they are not constant names means that just as there are originally no absolute names such as water or fire, likewise A way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way.

Next page