This book made available by the Internet Archive.

This edition is published by arrangement with The Macmillan Company

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 58-5092

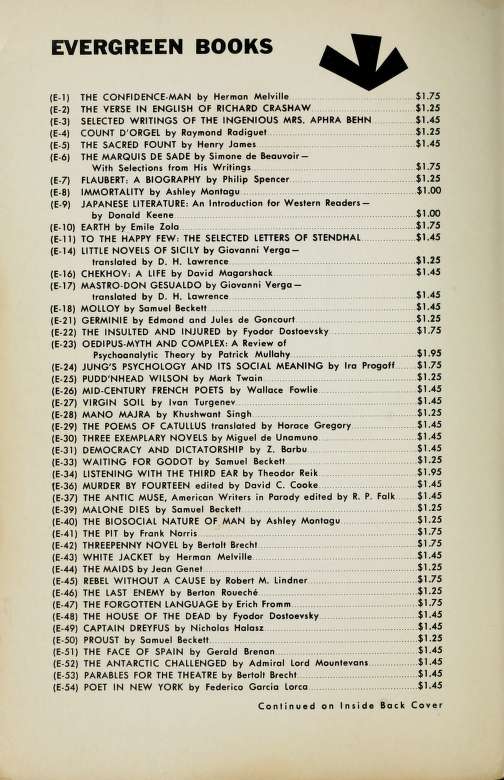

Grove Press Books and Evergreen Books

are published by Barney Rosset at Grove Press, Inc.

795 Broadway New York 3, N. Y.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

Leonard & Dorothy Eltnhirst

f<

PREFACE

I HAVE noticed that general works* about the history of Man either ignore China altogether or relegate this huge section of mankind to a couple of paragraphs. One of my aims in this book vs, to supply the general anthropologist with at any rate an impetus towards including China in his survey. This does not however mean that the book is addressed to a small class of specialists; for all intelligent people, that is to say, all people who want to understand what is going on in the world around them, are 'general anthropologists', in the sense that they are bent on finding out how mankind came to be what it is to-day. Such an interest is in no sense an academic one. For hundreds of millennia Man was what we call 'primitive'; he has attempted to be civilized only (as regards Europe) in the last few centuries. During an overwhelmingly great proportion of his history he has sacrificed, been engrossed in omens, attempted to control the wind and rain by magic. We who do none of these things can hardly be said to represent normal man, but rather a very specialized and perhaps very unstable branch-development. In each of us, under the thinnest possible veneer of homo industrialis, lie endless strata of barbarity. Any attempt to deal with ourselves or others on the supposition that what shows on the surface represents more than the mere topmast of modern man, is doomed to failure. And Man must be studied as a whole. Despite the lead

' e.g. A. M. Hocart's The Progress of Man, E. O. James's Origins of Sacrifice, both quite recent works.

The Way and its Power

given by unofficial historians there is still an idea that the Chinese are or at any rate were in the past so cut off from the common lot of mankind that they may be regarded almost as though they belonged to another planet, that sinology is in fact something not much less remote than astronomy and cannot, whatever independent interest or value it may have, possibly throw light on the problems of our own past. Nothing could be more false. It becomes apparent, as Chinese studies progress, that in numerous instances ancient China shows in a complete and intelligible form what in the West is known to us only through examples that are scattered, fragmentary and obscure.

It may however be objected that the particular book which I have chosen to translate is already well known to European readers. This is only true in a very qualified sense; and in order to make clear what I mean I must make a distinction which has, I think, too often been completely ignored. Supposing a man came down from Mars and seeing the symbol of the Cross asked what it signified, if he chanced to meet first of all with an archaeologist he might be told that this symbol had been found in neolithic tombs, was originally a procreative charm, an astrological sign or I know not what; and all this might quite well be perfectly true. But it still would not tell the Man from Mars what he wanted to knownamely, what is the significance of the Cross to-day to those who use it as a symbol.

Now scriptures are collections of symbols. Their peculiar characteristic is a kind of magical elasticity. To successive generations of believers they mean things that would be paraphrased in utterly different words. Yet for

Preface

century upon century they continue to satisfy the wants of mankind; they are 'a garment that need never be renewed'. The distinction I wish to make is between translations which set out to discover what such books meant to start with, and those which aim only at telling the reader what such a text means to those who use it today. For want of better terms I call the first sort of translation 'historical', the second 'scriptural'. The most perfect example of a scriptural translation is the late Richard Wilhelm's version of the Book of Changes. Many critics condemned it, most unfairly in my opinion, because it fails to do what in fact the author never had any intention of doing. It fails of course to tell us what the book meant in the loth century B.C. On the other hand, it tells us far more lucidly and accurately than any of its predecessors what the Book oj Changes means to the average Far Eastern reader to-day.

There are several good 'scriptural' translations of the Tao Te Ching. Here again I think Wilhelm's is the best, and next to it that of Carus.i But there exists no 'historical' translation; that is to say, no attempt to discover what the book meant when it was first written. That is what I have here tried to supply, fully conscious of the fact that to know what a scripture meant to begin with is perhaps less important than to know what it means to-day. I have decided indeed to make this attempt only because in this case the 'Man from Mars'the Western readerhas been fortunate enough not to address his initial questions to the archaeologist. More representative informants have long ago set before him the current (that is to say, the

' Or rather, of his Japanese collaborator.

The Way and its Power

medieval) interpretation of the Tao Te Ching, I feel that he may now be inclined to press his enquiries a little further; just as a tourist, having discovered what the swastika means in Germany to-day, might conceivably become curious about its previous history as a symbol. Fundamentally, however, my object is the same as that of previous translators. For I cannot believe that the study of the past has any object save to throw light upon the present.

I wish also to make another, quite different, kind of distinction. It has reference to two sorts of translation. It seems to me that when the main importance of a work is its beauty, the translator must be prepared to sacrifice a great deal in the way of detailed accuracy in order to preserve in the translation the quality which gives the original its importance. Such a translation I call 'literary', as opposed to 'philological'. I want to make it clear that this translation of the Tao Te Ching is not 'literary'; for the simple reason that the importance of the original lies not in its literary quality but in the things it says, and it has been my one aim to reproduce what the original says with detailed accuracy.

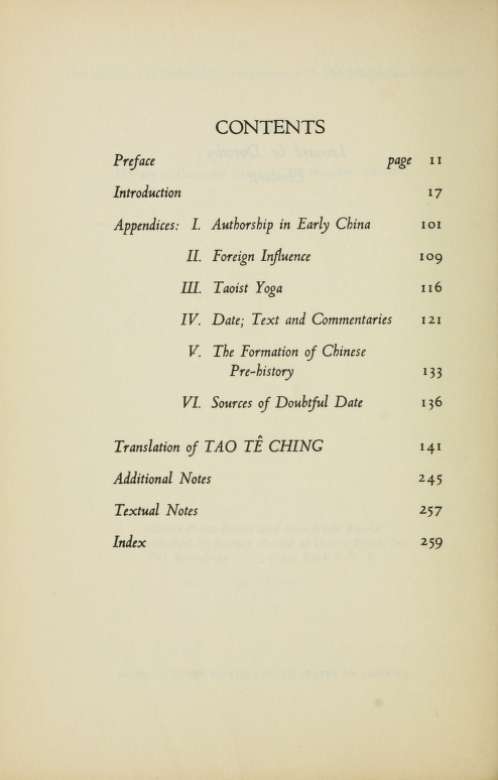

I must apologize for the fact that the introduction is longer than the translation itself. I can only say that I see no way of making the ttxt fully intelligible without showing how the ideas which it embodies came into existence. The introduction together with the translation and notes are intended for those who have no professional interest in Chinese studies. The appendices to the introduction and the additional and textual notes are intended chiefly for specialists. Thus the book represents a com

Preface

promiseof a kind that is becoming inevitable, as facilities for purely specialist publication become more and more restricted.