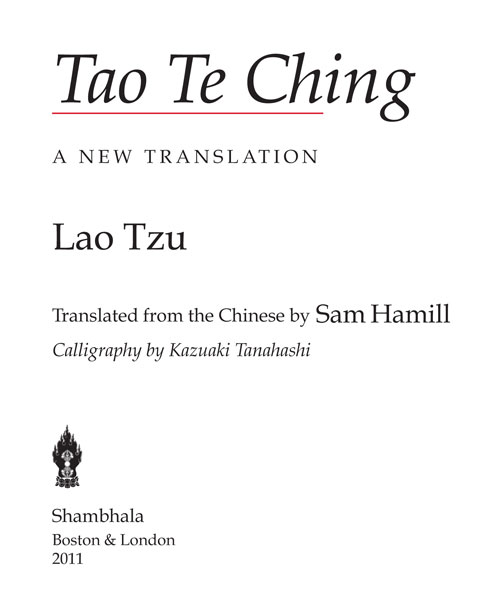

Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2005 by Sam Hamill Cover art by Kazuaki Tanahashi Foreword 2005 by Arthur Sze All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress catalogues the previous edition of this book as follows: [Dao de jing. English] Tao te ching: a new translation/Lao Tzu; translated from the Chinese by Sam Hamill; calligraphy by Kaz Tanahashi. cm. eISBN 978-0-8348-2299-3 ISBN 978-1-59030-011-4 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I.

Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2005 by Sam Hamill Cover art by Kazuaki Tanahashi Foreword 2005 by Arthur Sze All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress catalogues the previous edition of this book as follows: [Dao de jing. English] Tao te ching: a new translation/Lao Tzu; translated from the Chinese by Sam Hamill; calligraphy by Kaz Tanahashi. cm. eISBN 978-0-8348-2299-3 ISBN 978-1-59030-011-4 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I.

Hamill, Sam. II. Title. BL1900.L26E5 2005 299.51482dc22 2005007826 Contents The Tao Te Ching is a cornerstone of Chinese culture. The traditional view is that it was written by Lao Tzu, an older contemporary of Confucius (551479 B.C.E .). Composed in this early time, the thoughts and insights, acute and profound, are essential reading for today.

From its spellbinding and incantatory openingbeginning with four sets of three characters, extending to two sets of six charactersa swaying, mesmerizing rhythm is set in motion. There will never be a definitive translation of the Tao Te Ching . Chapter by chapter, phrase by phrase, there is no substitute for reading and experiencing the text in its original splendor. Nevertheless, translation is a necessary art, for few readers can read the ancient characters now. And for such a classic text, there is no end in sight for translations. Yet, although many translations of the Tao Te Ching now exist in English, few convey the clarity, complexity, and force of the original.

In his new translation of Lao Tzus Tao Te Ching, Sam Hamill resists any temptation to embellish or oversimplify or scatter New Age phrases over the text. His intention is to present clarity, depth, and intensity. In crucial chapter fourteen, for instance, Hamill brings three aspects of the Tao to the readers attention: its invisibility, its inaudibility, and its intangibility: Looking and not seeing it,we call it invisible;listening and not hearing it,we call it inaudible;reaching and not touching it,we call it ethereal.These three aspects of it cannot be grasped,but contribute to the one.Its rising brings no dawn,its setting no darkness;it goes on and on, unnamable,returning into nothingness.Its form is formless.Its image is invisible.Meeting it, you cannot see its face.Following it, you cannot see its back.Hold to the ancient Taoto grasp the here-and-now.Discovering how things have always beenbrings one into harmony with the Way. Here, then, is Sam Hamills translation: unadorned, close to the text, and honoring its original energy. Arthur Sze Lao Tzu, the Old Master, came and went like the wind in the sixth century B.C.E . But in his passing, he left behind an eternal thunderbolt.

Born in the state of Chu half a century before the great Kung-fu Tzu (Confucius 551479 B.C.E .), his life is mostly legend. Ssu-ma Chiens Records of the Historian (100 B.C.E .) place him in the Chou capital of Loyang, working as historical archivist for the court, having come from the rich delta of the Yellow River, where shamanism was a cultural influence. Legend has the old sage, by name Li Erh-tan, losing his library amidst the crumbling Chou empire and fleeing through Han-ku Pass in the West. There he was questioned by the border guard about the nature of tao and te . Lao Tzu, it is said, sat there one evening and wrote out the Five-Thousand-Word Classic in two parts before disappearing from the world (or into it). Chinese literary history overflows with such apocryphal legends.

In all likelihood, Lao Tzu compiled and edited the Tao Te Ching to a far, far greater extent than actually writing it. The text is full of folk sayings, lines from folk songs, and poetic and philosophical tidbits often surprisingly juxtaposed. There are variant texts and there is no certifiable original so the text of the Old Master himself has probably been corrupted. How much of this is the result of subsequent anonymous editors is anyones guess. For a couple of centuries, the most famous book in the Chinese pantheon didnt even have a title. 516 B.C.E .), the former was in his mid-thirties, the latter likely in his late eighties. 516 B.C.E .), the former was in his mid-thirties, the latter likely in his late eighties.

Master Kung remarked afterward, He is a dragon among men. The Old Dragons The-Way-and-Its-Virtue Classic has kept people intrigued and learning for two and a half millennia. When encountered, interpreted, and incorporated by early Chinese Buddhists over a thousand years ago, it produced Chan (Zen) Buddhism and the practice of what we know most commonly by its Japanese name, shikantaza, deep sitting meditation. Taoist-like use of paradox is everywhere evident in Zen koan or case. Taoism also grew into a religion and various kinds of cults, all sorts of sects that grew increasingly farther away from the teachings of Lao Tzus classic. During the collapse of the Chou dynasty, there was a lot of philosophical argument between the Confucians and their main rivals, the Mohists.

The Confucians believed in building the state through the structure of the family, and that filial piety and philosophical and familial lineation could best build a strong state. Mohists argued in favor of a meritocracy and against the idea that the emperor could actually be the Son of Heaven. Both philosophies were devoted to empire building. Both argued by quoting ancient sages, historical precedent, and anecdote. Some scholars have claimed the Tao Te Ching as a philosophical argument against Confucianism, Mohism, and the whole notion of empire. Lao Tzu clearly preferred a smaller, less-threatening, less-powerful state.

But unlike the philosophical texts of its time, the Tao Te Ching makes no reference to historical times or personae and cuts directly through the Chinese traditions of formal argument. Some have claimed the Tao Te Ching as a political or military treatise; others explicate its existential metaphysics. All are, to a degree, correct. Master Kung also spoke about a way in the Ta Hsueh (Great Learning) and elsewhere, but the Confucian way is one to be studied and attained; it is a purely human way based on the teachings and inspiration of old masters, a way of character building rooted in virtuous behavior. Lao Tzus Tao is more the way-of-nature, not something earned, but something inherently within all beings and to which we must become attuned if we are to live wisely and harmoniously for our time in this world. These two paths sometimes worked harmoniously, but often conflicted.

Give up all attainment! Lao Tzu cries, and the good Confucian replies, Agreed. To give up attainment is to attain transcendence. Such a person is fit to lead. The classical Chinese mind enjoyed the arguments between the primary schools of philosophy, drawing from each, and, centuries later, adding the fundamental philosophy of Buddhism to create san chiao, three interlocking, cross-pollinating systems of thought from which arose the great cultures of the Tang and other periods. In classical Confucian poets, one finds elemental Taoism; in Buddhist poets, elemental Confucianism. Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism became the intricately interwoven threads that produced the great complex fabric of classical Chinese culture.

Chuang Tzu says, A great persons words are as simple and clear as water, while a small ones words are sweet as wine. In our age of political and social doublespeak and psychobabble, his observation cuts two ways and rings as true as ever. Lao Tzus clear, simple language harbors great complexity within. Even the character for tao is simultaneously simple and complex. For centuries the character

Next page

Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2005 by Sam Hamill Cover art by Kazuaki Tanahashi Foreword 2005 by Arthur Sze All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress catalogues the previous edition of this book as follows: [Dao de jing. English] Tao te ching: a new translation/Lao Tzu; translated from the Chinese by Sam Hamill; calligraphy by Kaz Tanahashi. cm. eISBN 978-0-8348-2299-3 ISBN 978-1-59030-011-4 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I.

Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2005 by Sam Hamill Cover art by Kazuaki Tanahashi Foreword 2005 by Arthur Sze All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress catalogues the previous edition of this book as follows: [Dao de jing. English] Tao te ching: a new translation/Lao Tzu; translated from the Chinese by Sam Hamill; calligraphy by Kaz Tanahashi. cm. eISBN 978-0-8348-2299-3 ISBN 978-1-59030-011-4 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I. paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-387-0 (paperback) I.