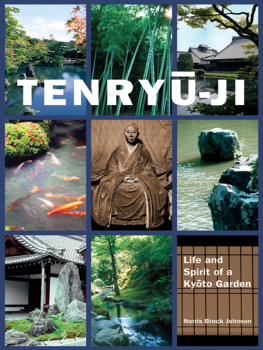

Tenry-ji

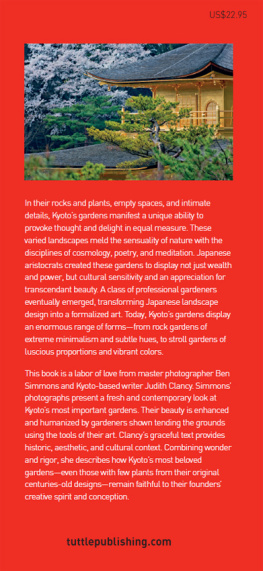

LIFE AND SPIRIT OF A KYTO GARDEN

Norris Brock Johnson

Stone Bridge Press Berkeley, California

Published by

Stone Bridge Press

P.O. Box 8208

Berkeley, CA 94707

TEL 510-524-8732

Cover and text design by Linda Ronan.

Photographs by the author unless otherwise indicated. Copyright notices accompany their respective images. Image credits and permissions appear after the Index.

2012 Norris Brock Johnson.

First edition 2012.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Johnson, Norris Brock.

Tenryuji: life and spirit of a Kyoto garden / Norris Brock Johnson.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61172-004-4.

I. Tenryuji (Kyoto, Japan) 2. Zen templesJapanKyoto. 3. Gardens, JapaneseJapanKyoto. 4. Gardens, JapaneseZen influences. 5. Church gardensJapanKyoto. I. Title. II. Title: Life and spirit of a Kyoto garden.

SB458.J64 2012

712.09521864dc23

2011044825

For my ancestors

Beatrice Brock, 18921957

Richard Lawrence Johnson, 194886

Alfreda Belle Johnson, 191095

Rufus Norris Johnson, 190299

I

MOUNTAINS, WATER, AND FRAGRANT TREES

Prior to the seventh century, it had been the custom to abandon the court of an emperor or empress after their death, as each site was then considered polluted. New sites, purified places, were prepared for each successive emperor or empress. Imperial courts grew in size, and relocations increasingly became cumbersome; in time, imperial coursts became semipermanent, then permanent.

In 710, during the reign of Empress Genmy (Genmei, 660721), Nara (Heij-ky, Capital of the Peaceful Citadel) became an influential capital city for imperial courts. Rather than defer to concerns over death and pollution, selection of the site for the Capital of the Peaceful Citadel in large part was based on then-favorable aspects of the surrounding area, in particular, the sensory delights afforded to people of privilege through aesthetic experiences of the Yamato Plain.

Nara (Level Land), though, increasingly became subject to periodic flooding as the imperial city had been sited near the Saho and Tomio rivers. Aesthetic enjoyment of the area around Nara did not offset the growing belief that the land itself was failing to influence the well-being of emperors, the city, and its people.

Virtue and the Breath of Life

Changing conceptions of and attitudes toward the land and landscape around Nara influenced temporary relocation of the imperial capital, in 784, to Nagaoka. In 794, Emperor Kanmu (737806) ordered the imperial capital moved from Nara to a new site that became known as the Capital of Peace and Tranquillity (Kyto).

The land on which Kyto was sited had been donated to Emperor Kanmu by the Hata family, wealthy descendants of immigrants from Korea. Kyto was believed to be free of the malevolent influences causing undesirable environmental changes within areas in and around Nara. At this time, nature (, shizen) was believed to embody animistic qualities demonstrably affecting peopleland and human-created landscapes were auspicious, or not, and favorably influenced well-being, or not. People of influence felt that the site and topography of Nara were not balancing wind and water, but increasingly favored water. They believed that the area north of Nara better balanced wind and water.

Principles and practices for enhancing aspects of nature deemed beneficent were known as Storing Wind/Acquiring Water (, zf tokushi), which coexisted with imported Chinese feng shui principles and practices of Wind/Water.

Feng shui animistically conceived of the earth as an organic body laced with arterial veins through which the Breath of Life (qi; , ki in Japan) flowed. The Breath of Life flowed and circulated more intensely in some spaces and places more than in others. Well-being was enhanced through detecting intensive flows of the Breath of Life embodied as distinctive features of the land itself, then through fashioning habitats congruent with the flow of the Breath of Life. By the ninth century, the rudiments of feng shui were present in Japan; indeed, the senior Ministry of State, the Nakatsukasa, included a special department, the Onmy-Ry (, Bureau of Yin-Yang), with a select staff of masters and doctors of divination and astrology. During the later Southern Sung Dynasty, Buddhist priests from China studied in Japan and Buddhist priests from Japan studied in China. The Ajari, for instance, were Japanese Buddhist specialists in Chinese yin yang (, in y in Japan).

Selection of the site on which Kyto was constructed acknowledged the influence of nature on the well-being of people, in particular the influence of a favorable balancing of mountains and water.

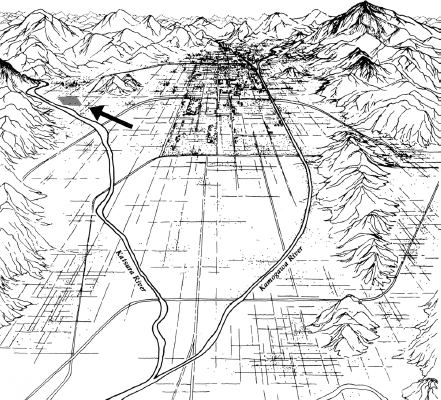

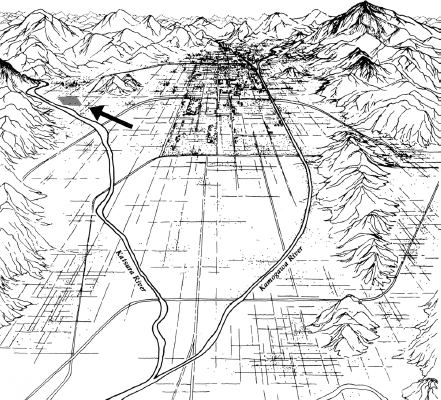

Favorably open toward the south, Kyto was laid out on a plain between auspicious aspects of nature to the north, east, and west.With protecting hills and mountains to the north, east, and west, Kyto was sited within a beneficent space between tiger (west) and the dragon (east) mountains.

Kyto was sited with respect to the Katsura River and the Kamo River, both of which flowed auspiciously toward the south into low-lying basins fed by numerous springs flowing down from surrounding mountains. Interestingly, the mountains surrounding the City Kyto was auspiciously sited within a low-lying basin surrounded on three sides by mountains with the fourth side, the south side, open to the flowing waters of rivers, a siting believed to enhance the well-being of the city and its inhabitants (figs. 2, 30).

FIGURE 30. The city of Kyto was sited within a basin surrounded, and balanced, by (tiger) mountains to the west and (dragon) mountains to the east. Tenry-ji (toward where the arrow is pointing), a dragon presence, subsequently was sited within, and balanced by, the tiger-mountains to the west of the city.

Kyto also was known as the City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams In the section Revealing the Nature of Buddha-Nature, for instance, we will see that in the fourteeenth century the landscape of the temple included features such as a Dragon-Gate Pavilion, the fabled Moon-Crossing Bridge, and a shrine evocatively renamed Buddhas Light of the Worldarchitectured features placed in nature some distance from the central areas of the temple.

Wind circulates the Breath of Life. Water embraces the Breath of Life. The chi, the cosmic breaths which constitute the virtue of a site, are blown about by the wind and held by the waters. A circulating balance of wind and water was believed not only to be auspicious, beneficent, but to be virtuous as well.

The Temple of the Heavenly Dragon, much later, will be sited within a balanced, auspicious confluence of low-lying bodies of water nestled within encircling mountains (fig. 5). Locating the temple amid mountains and water long associated with well-being by contagious contact was believed to enhance the moral character and mission of the complex. The temple was considered a repository of virtue, as we will see, an especially beneficent place for the living as well as for the deceased.

A Most Beautiful Meadow

After the capital had been relocated from Nara to Kyto, a succession of emperors and aristocrats began to find favor with Sagano (Saga), a lush region within the mountains west of Kyto, for the location of compounds built as retreats from the city (fig. 2). Sagano was praised as the best meadow of all, no doubt because of its beauty as a landscape. igawa (the Abundant-Flowing River), merging with the Katsura River, flowed through Sagano. The Mountain of Storms lay to the west/southwest of the river while Turtle Mountain and the plains of Sagano lay to the north/northeast of the river.

Next page