The Legacy of

Wilfred Cantwell Smith

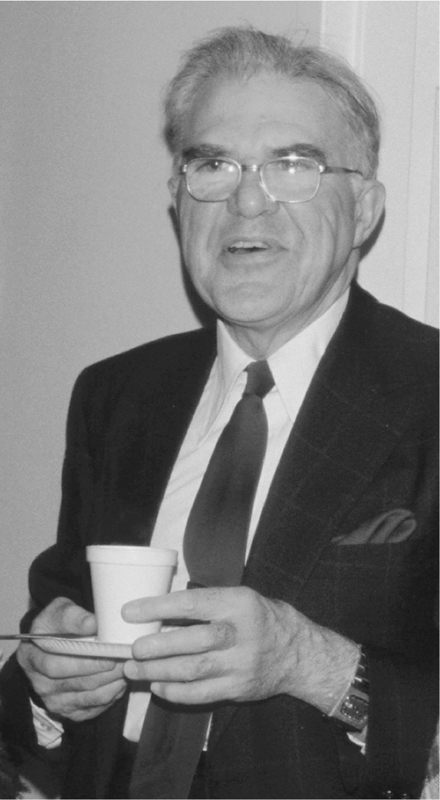

Wilfred Cantwell Smith (19162000). Photo courtesy of Diana Eck.

The Legacy of

Wilfred Cantwell Smith

Edited by

ELLEN BRADSHAW AITKEN

and

ARVIND SHARMA

Published by

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

Albany

2017 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact

State University of New York Press

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Jenn Bennett

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Aitken, Ellen Bradshaw, editor | Sharma, Arvind, editor

Title: The legacy of Wilfred Cantwell Smith / Ellen Bradshaw Aitken and Arvind Sharma, editors.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781438464695 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438464701 (e-book)

Further information is available at the Library of Congress.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Ellen Bradshaw Aitken and Arvind Sharma

Diana L. Eck

Religious StudiesThe Academic and Moral Challenge:

Personal Reflections on the Legacy of Wilfred Cantwell Smith

John B. Carman

Purushottama Bilimoria

Thomas B. Coburn

Anticipating the Emergence of Contemplative Studies:

Reflections on the Work of Wilfred Cantwell Smith

Harvey Cox

William A. Graham

John Stratton Hawley

Jonathan R. Herman

Amir Hussain

Sheila McDonough

Robert A. Segal

Peter Slater

K. R. Sundararajan

Donald K. Swearer

Introduction

E LLEN B RADSHAW A ITKEN AND A RVIND S HARMA

I

Professor Wilfred Cantwell Smith (19162000) left a deep impression on the study of religion, and his influence has only grown with the passage of time. The Faculty of Religious Studies at McGill University, of which he was once a member, held a symposium on November 6, 2009, to honor and assess this legacy. This volume is the precipitate of that symposium.

II

The legacy of Wilfred Cantwell Smith is of course only further proof of his continuing impact on the academic study of religion, an impact that was already obvious during his teaching and writing career. It may not be out of place to reprise the contribution he made while alive, to help pave the way for assessing his legacy.

Smith received a BA (honors) in Oriental Languages from the University of Toronto in 1938 and went on to pursue higher studies at Cambridge University, where he worked under the famous Islamicist, H. A. R. Gibb. Smith at the time was inclined toward Marxism, and was critical of the British and their approach to the communal problem, as Hindu-Muslim tensions in India were called at the time. His thesis was therefore rejected. He thereafter taught Indian and Islamic history at the Forman Christian College in Lahore from 1941 onward, and was an eyewitness to the Independence and Partition of India in 1947. His days in Lahore are discussed in detail in this book, in the chapter by Sheila McDonough. He then obtained a PhD in Oriental Languages from Princeton University and began teaching at McGill University, where he founded the Institute of Islamic Studies. Subsequently, Smith served as the director at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard University (196473), and then founded the Department of Religious Studies at Dalhousie University in Halifax. He returned to Harvard University in 1978, to work with the Harvard Committee on the Study of Religion. After retiring in 1985, he became a senior research associate of the Faculty of Religious Studies at Trinity College, University of Toronto, and was awarded the Order of Canada in 2000, the year he died. John Carmans essay in this volume explores these various dimensions of Smiths legacy.

III

Smiths influence radiated in pedagogical circles through his numerous students (many of whom have contributed to this volume), but it was in his role as a writer that he exerted his influence over larger academia. In this regard, two broad phases can be discerned; in one, his primary focus was Islam, and in the other, it was religion as such. Smiths early career and his work in Cambridge and Lahore concentrated on Islam; the establishment of the Institute of Islamic Studies at McGill University was perhaps the most visible manifestation of this aspect of his work. The emergence of the next phase is represented by the publication, in 1959, of an essay, Comparative Religion: Whitherand Why? in a volume entitled History of Religions: Essays in Methodology , edited by Mircea Eliade and J. Kitagawa.

It is worth recalling that Islam as a religion, and Islamic studies as a branch of academia, did not enjoy the profile in Smiths time that it does today. In fact, when Smith was pursuing Islamic studies, one rarely spoke of the Abrahamic tradition, an expression that places Judaism, Christianity, and Islam under the same umbrella. One spoke, rather, of The public profile of Islam became more prominent after the Iranian revolution in 1979, and even acquired a spectral dimension after the events of September 11, 2001. An Islamic presence is now an inescapable feature of the international landscape, but such was not the case when Smith embarked on its study, almost intuiting the role Islam was destined to play in world affairs.

The nature of Smiths contribution to the study of Islam is equally significant, apart from the fact of his having presciently engaged in it, and is best dramatized by the fact that there is not a single reference to Professor Wilfred Cantwell Smith in the book that created such a sensation in Islamic studies, Edward Saids Orientalism . It had a neutral connotation. After the publication of the book the word acquired a pejorative connotation, as a result of the books claim that such a study of the Orient is inescapably tainted by the ruler-ruled relationship that obtained between the Occident and the Orient. It is perhaps not unfair to assume that Said did not, or would not, or could not, refer to Smith, because he did not find his scholarship of the Orient to be tainted in this way. William Grahams essay in this volume bears on this issue.

That Smith could, even when writing during the age of imperialism, escape its intellectual consequences could well be the outcome of the attitude that Smith espoused toward the study of religion itself, which remains to this day a powerful element in his legacy. Smith discusses the evolving attitudes to the study of religion in his seminal essay referred to earlier, which has been summarized by Frank Whaling as follows:

In this essay, Smith traced the progress in the study of the History of Religions in various stages. The first stage saw the accumulation and analysis of facts. At first there was the impersonal accumulation of facts about they, the people of a religion, by scholars still personally uninvolved. The next