Table of Contents

The Heart Sutra

The Heart Sutra

1 The noble Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva,

while practicing the deep practice of Prajnaparamita,

looked upon the Five Skandhas

and seeing they were empty of self-existence,

5 said, Here, Shariputra,

form is emptiness, emptiness is form;

emptiness is not separate from form,

form is not separate from emptiness;

whatever is form is emptiness,

whatever is emptiness is form.

The same holds for sensation and perception,

memory and consciousness.

10 Here, Shariputra, all dharmas are defined by emptiness

not birth or destruction, purity or defilement,

completeness or deficiency.

Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness there is no form,

no sensation, no perception, no memory and no

consciousness;

no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body and no mind;

15 no shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, no feeling

and no thought;

no element of perception, from eye to conceptual

consciousness;

no causal link, from ignorance to old age and death,

and no end of causal link, from ignorance to old age and death;

no suffering, no source, no relief, no path;

20 no knowledge, no attainment and no non-attainment.

Therefore, Shariputra, without attainment,

bodhisattavas take refuge in Prajnaparamita

and live without walls of the mind.

Without walls of the mind and thus without fears,

25 they see through delusions and finally nirvana.

All buddhas past, present and future

also take refuge in Prajnaparamita

and realize unexcelled, perfect enlightenment.

You should therefore know the great mantra of Prajnaparamita,

30 the mantra of great magic,

the unexcelled mantra,

the mantra equal to the unequalled,

which heals all suffering and is true, not false,

the mantra in Prajnaparamita spoken thus:

Gate gate, paragate, parasangate, bodhi svaha.

Introduction

T HE Heart Sutra is Buddhism in a nutshell. It covers more of the Buddhas teachings in a shorter span than any other scripture, and it does so without being superficial or commonplace. Although the author is unknown, he was clearly someone with a deep knowledge of the Dharma and an ability to summarize lifetimes of meditation in a few well-crafted lines. Having studied the Heart Sutra for the past year, I would describe it as a work of art as much as religion. And perhaps it is one more proof, if any were needed, that distinguishing these two callings is both artificial and unfortunate.

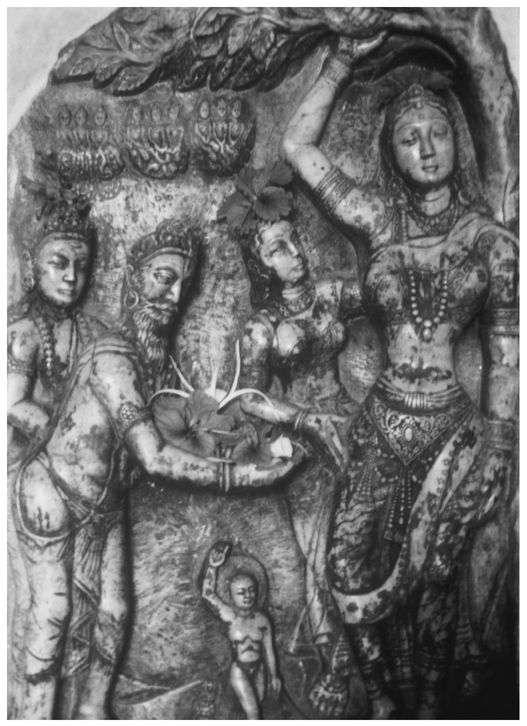

Whoever the author was, he begins by calling upon Avalokiteshvara, Buddhisms most revered bodhisattva, to introduce the teaching of Prajnaparamita, the Perfection of Wisdom, to the Buddhas wisest disciple, Shariputra. Avalokiteshvara then shines the light of this radical form of wisdom on the major approaches to reality used by the Sarvastivadins, the most prominent Buddhist sect in Northern India and Central Asia two thousand years ago, and outlines the alternative approach of the Prajnaparamita. Finally, Avalokiteshvara also provides a key by means of which we can call this teaching to mind and unlock its power on our behalf.

With this sequence in mind, I have divided the text into four parts and have also broken it into thirty-five lines to make it easier to study or chant. In the first part (lines 1-11), we are reminded of the time when the Buddha transmitted his entire understanding of the Abhidharma, or Matrix of Reality, during the seventh monsoon following his Enlightenment. We then consider Avalokiteshvaras reformulation of such instruction to correct Shariputras misunderstanding of it. The basis for this reformulation is the teaching of prajna in place of jnana, or wisdom rather than knowledge. Thus, the conceptual truths on which early Buddhists relied for their practice are held up to the light and found to be empty of anything that would separate them from the indivisible fabric of what is truly real. In their place, Avalokiteshvara introduces us to emptiness, the common denominator of the mundane, the metaphysical, and the transcendent.

In the second part (lines 12-20), Avalokiteshvara lists the major conceptual categories of the Sarvastivadin Abhidharma and considers each in the light of Prajnaparamita. Following the same sequence of categories used by the Sarvastivadins themselves, he reviews such forms of analysis as the Bodies of Awareness, the Abodes of Sensation, the Elements of Perception, the Chain of Dependent Origination, the Four Truths, and the attainment or non-attainment of Nirvana, and sees them all dissolve in emptiness.

In the third part (lines 21-28), Avalokiteshvara turns from the Sarvastivadin interpretation of the Abhidharma to the emptiness of Prajnaparamita, which provides travelers with all they need to reach the goal of buddhahood. Here, Avalokiteshvara reviews the major signposts near the end of the path without introducing additional conceptual categories that might obstruct or deter those who would travel it.

In the fourth part (lines 29-35), Avalokiteshvara leaves us with a summary of the teaching of Prajnaparamita in the form of an incantation that reminds and empowers us to go beyond all conceptual categories. This teaching has with good reason been called the mother of buddhas. Having survived a yearlong journey through the jungle of early Buddhism to the secret burial ground of the Abhidharma, I would add that the Heart Sutra is their womb. With this incantation ringing in our minds, we thus enter the goddess, Prajnaparamita, and await our rebirth as buddhas. This is the teaching of the Heart Sutra, as I have come to understand it over the past year.

KARMIC BACKGROUND

In the fall of 2002, I was working on a translation of the Lankavatara Sutra when my friend Silas Hoadley asked me if I would contribute a new English version of the Heart Sutra for a meditation retreat he was organizing just outside the small town where we live. I was glad to take a break from the Lanka and began comparing Sanskrit editions and Chinese translations and poring over commentaries. Although I had first encountered the Heart Sutra more than thirty years earlier and had read the standard explanations of its meaning, I had never thought of it as anything more than a superficial summary of the Buddhist concept of shunyata, or emptiness. I failed to see anything in it of interest beyond the line: form is emptiness, emptiness is form, not that this made much sense to me.

This time I didnt even get past the name: the Heart Sutra. I discovered that there was no record of this title until Hsuantsangs Chinese translation of the text appeared in 649, four hundred years after the first translation into Chinese. This in turn led me to wonder how the Chinese word hsin, or heart, ended up as the name of what has become the best known of all Buddhist scriptures. Since hsin is the standard Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word hridaya, I began poking around and found three Sanskrit works whose titles also contained the word hridaya. Known collectively as the hridaya shastras (a shastra being an exposition of doctrine by later followers of the Buddha), these were among the most influential accounts of the Abhidharma of the Sarvastivadin sect of early Buddhism. They included a work by Dharmashri (c. 100 B.C.), another by Upashanta (C. A. D. 280), and a third by Dharmatrata (C. A. D. 320). These three shastras were considered essential reading for members of the Sarvastivadin sect, and they eventually formed the basis of an Abhidharma school in China. I couldnt help wondering if their popularity had something to do with the name change that occurred sometime between the appearance of Chih-chiens Heart Sutra translation around A.D. 250, when he gave the text the title of Prajnaparamita Dharani, and 649, when Hsuan-tsang titled it Hsin-ching, or Heart Sutra.