ABOUT THE BOOK

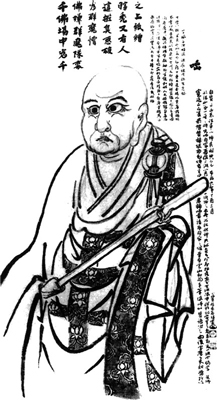

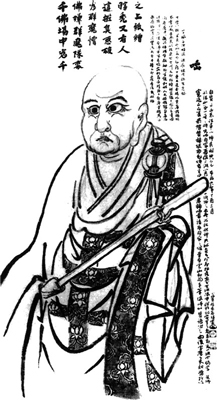

Hakuin Zenji (16891769) was one of the most important of all Japanese Zen masters. His commentary on the Heart Sutra is a Zen classic that reflects his dynamic teaching style, with its balance of scathing wit and poetic illumination of the text. Hakuins sarcasm, irony, and invective are ultimately guided by a compassion that seeks to dislodge students false assumptions and free them to realize the profound meaning of the Heart Sutra for themselves. The text is illustrated with Hakuins own calligraphy and brush drawings.

NORMAN WADDELL is a professor of international studies at Otani University in Kyoto, Japan. He is also the translator of The Essential Teachings of Zen Master Hakuin.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Self-Portrait by Hakuin

Zen Words for the Heart

Hakuins Commentary on The Heart Sutra

Translated by Norman Waddell

Shambhala

Boston & London

2013

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1996 by Norman Waddell

Cover art: Half Body Daruma by Hakuin Ekaku, courtesy of the Gitter Collection. Darumas robe is formed by the character for heart.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Hakuin, 16861769

[Hannya shingy dokugoch. English]

Zen words for the Heart: Hakuins commentary on the Heart Sutra/translated by Norman Waddell.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2832-2

ISBN 1-57062-165-9 (alk. paper)

1. Tripiaka. Strapiaka. Prajpramit. HdayaCommentaries.

I. Title.

BQ1965.H3413 1996 | 95-43420 |

294.385dc20 | CIP |

BVG 01

For Yoshie

Publishers Note

This book contains diacritics and special characters. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader device to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

The Sacred Tortoises tail sweeps her tracks clear. But how can the tail avoid leaving traces of its own?

Zen Words for the Heart (Dokugo shingy in Japanese) is a commentary on the Heart Sutra by the Japanese monk Hakuin Ekaku, 16861768. It brings together one of the great masters of Zen history and a scripture many rank among the most sublime documents of the human spirit.

Hakuins commentary derives in large part, if not entirely, from lectures he delivered on the Heart Sutra at a practice meeting held in the winter of 1744 at a country temple in the province of Kai (present-day Yamanashi prefecture), near Mount Fuji.to dislodge assumptions and hardened preconceptions in the minds of students and to free them to find deeper self-understanding in the profound but highly abstract series of negations the sutra offers up to them.

Like the thirty or so other works that make up the prajna, or Wisdom, family of sutras, the teaching in the Heart Sutra focuses on the fundamental Buddhist doctrine of shunyata or emptiness. Although one of the briefest works in the Buddhist canon, the sutra is thought to embody within its two hundred and seventy Chinese charactersless than a page of textthe heart or essence of the Wisdom philosophy that is developed with great richness and resonance in such kindred sutras as the Large Prajnaparamita Sutra, an enormous work that amplifies the wisdom theme for fully six hundred volumes.

Through the centuries the Heart Sutra has been the most popular and widely used religious text in all East Asia. It is chanted on virtually every occasion in the Zen school and in most other Buddhist sects as well. There are few Buddhist followers unable to recite it by heart.

The teaching of the sutra is preached by the Bodhisattva Free and Unrestricted Seeing (Kanjizai in Japanese). This Bodhisattva, who is one of the most popular figures in the Mahayana Buddhist pantheon, is perhaps better known to Westerners by the Sanskrit name Avalokiteshvara, or the Chinese name Kuanyin. The Bodhisattva preaches at the request of Shariputra, who is reputed to be the wisest of the Buddhas disciples. Shariputra represents the teachings of the sage or Arhat, the ideal Buddhist disciple of the older Small Vehicle or Hinayana tradition that arose after the death of the Buddha and flourished prior to the appearance of the Mahayana teaching.

In setting forth the essentials of the prajnaparamita, the perfection of wisdom, the Bodhisattva reveals to Shariputra how wisdom is achieved and the other shore of nirvana is reached through a process of negation in the course of which all existence and all assertions about existence, including the classic tenets of Buddhism, are shown to be empty and void of substance.

The Heart Sutra was probably composed in India about fifteen hundred years ago and was translated not long after that into Chinese. Since that time it has been explained and elucidated countless times. Commentaries in Japan alone run well into the hundreds, ranging from sophisticated expositions of Buddhist philosophy to simple religious tracts for the faithful. Generally, though, they all attempt to spell out the sutras terse assertions along more or less rational lines. Primary appeal is to the intellect. Even those by monks with the most hardnosed reputations seem somehow conventional and well-mannered, more Buddhist than Zen, compared with the incisiveness and radical, shake-all attitude Hakuin brings to the text.

This quality, coupled with the vivid, paradoxical style characterizing Hakuins half-jokingbut totally seriouscomments has earned the work its reputation as one of the classics of Japanese Zen. Since the first printed edition appeared in the mid-eighteenth century it has been a standard text in monasteries, where teachers use it in conjunction with Zen teish, or lectures, to increase its effectiveness as a practical aid to training.

Hakuins own title for the work, Dokugo shingy, translates into English as Poison Words for the Heart. The practice of attaching caustic, stinging comments in prose and verse to the words and phrases of Buddhist sutras and other texts has been a tradition among Zen teachers at least since the Sung dynasty. It was then that the most famous examples of the genrethe Blue Cliff Record (Pi-yen lu) and the Gateless Barrier (Wu-men kuan)were composed. In Japan, where the tradition of capping verses goes back almost as far, Hakuin is widely regarded as one of the greatest exponents of the art. The virulence of his poison has become proverbial among the followers of his school. One drop, it is said, even a single word, can be fatal, destroying the universe and everything in it. They are quick to explain, however, how it works as a powerful medicine, pumping spiritual life into the dead letters of the sutra so they will work for students instead of against them, and how the master always doled it out with loving hands, an act of deepest compassion. Hakuin knew from his own religious struggle that it is only through the experience of what Zen calls the great death that students can emerge into the great life that lies beyond.

Next page