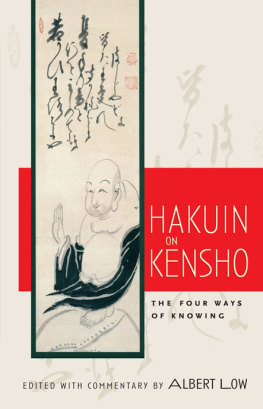

ABOUT THE BOOK

Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to ones own true natureof understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (16891769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho-realization of the Buddhas way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.

Hakuins short text on kensho, Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person, is a little-known Zen classic. The four ways he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for checking for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice.

ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Shambhala Publications

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2006 by Albert Low

Cover art: The Sound of One Hand Clapping by Hakuin Ekaku. The inscription reads: All you clever young people / No matter what you say, / If you dont hear the sound of one hand, / Everything else is rubbish! Courtesy of a private collection.

Cover design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronicor mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Low, Albert.

Hakuin on kensho: the four ways of knowing/edited with commentary by Albert Low.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2622-9

ISBN 978-1-59030-377-1 (alk. paper)

1. Hakuin, 16861769. I. Title.

BQ9399.E597L69 2006

294.3420427dc22

2006013420

Dedicated to my first Zen Teacher, Yasutani Roshi

CONTENTS

A T THE BEGINNING of his book Wild Ivy, the eighteenth-century Rinzai Zen master Hakuin says, Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first of all achieve kenshorealization of the Buddhas way. Throughout his life Hakuin would sound this clarion call, exhorting all who would listen to him to strive to their utmost to come to kensho, or awakening. He quoted Bodhidharma, who said:

If someone without kensho makes a constant effort to keep his thoughts free and unattached, not only is he a great fool, he also commits a serious transgression against the dharma. He winds up in the passive indifference of empty emptiness, no more capable of distinguishing good from bad than a drunken man. If you want to put the dharma of non-activity into practice, you must put an end to all your thought attachments by breaking through into kensho. Unless you have kensho, you can never expect to attain a state of non-doing.

What sets Hakuin apart from other teachers is the vigor with which he pointed to the importance of kensho and the diligence with which he followed his own teaching. He laughed at teachers who scorned kensho as unnecessary or even impossible, saying, [This kind of teacher] reminds you of someone who doesnt have the strength to raise his food up to his mouth to eat, yet who insists he isnt eating because the food is bad.

A passionate defender of the Buddhas way, Hakuin could be vitriolic when talking of monks who were undisciplined and unappreciative of the dharma: I have always loathed monks of their type. They are tiger fodder, no doubt about it. I hope one tears them into tiny shreds. The pernicious thieveseven if you killed off seven or eight of them every day, you would still remain totally blameless. Why are we so infested with them? Because the ancestral gardens have been neglected. They have run to seed. The verdant Dharma foliage has withered and only a wasteland remains.

Hakuins distain for the misleading guidance of Zen teachers who had not themselves attained kensho is reminiscent of Jesuss railing against the scribes and Pharisees in Matthew: But woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for you shut up the kingdom of heaven against men: for you enter not in yourselves, neither suffer you them that are entering to go in.... Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for

Hakuin clearly recognized that the practice of Zen is a formidable undertaking,

Koan study starts with the breakthrough koans of Mu! or What was your face before your parents were born? or, later, Hakuins own, What is the sound of one hand clapping?practice was first introduced into Zen Buddhism during the golden age of Zen, which lasted from about the sixth century until the tenth century. By the time of Hakuin, koan practice was in decline, and one of his great contributions was to revive koan study and make it once more a living part of the Zen way. For this reason, many Rinzai masters of today trace their dharma ancestry back to Hakuin.

Hakuin not only tirelessly advocated delving into the koans, he also insisted on the need to read and study the works of Buddhism, including the ancient Zen masters. His biographer, Torei, said, The words and sayings of the Zen masters never left his side. He used them to illuminate the old teachings by means of the mind, to illuminate the mind by means of the old teachings. (the aroused, unobstructed mind), which, no doubt, is why he did so much of it.

Hakuin was born in 1686 and by the age of fifteen was already ordained in the Zen tradition. He practiced what he taught and knew well the bitter struggles of Zen. At one time he became so disillusioned with Zen practice that he gave it up in favor of reading and studying contemporary Chinese and Japanese literature. Even so, he returned to the practice and continued his training until the age of thirty-five, when he began to teach, not only monks, but laypeople as well.

Like many people who go on and wont give up the practice of Zen, Hakuin was driven by great anxiety and anguish. This anguish afflicted him early in his life. He tells of one occasion when he was scared out of his wits by the hot water of the bath. He cried out to his mother in terror:

When he later became disillusioned with Zen, his acute anxiety was the cause. He had heard that the great Zen master Ganto had met a violent death at the hand of bandits, and, he wrote, Wanting to learn more about the life of this priest, I got hold of a copy of

Next page