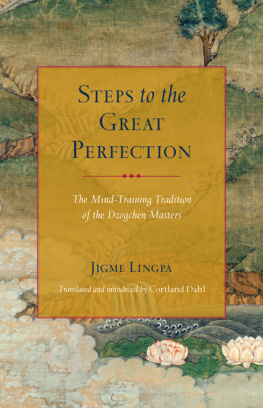

A Trackless Path

A commentary on the great completion (dzogchen) teaching of Jigm Lingpas Revelations of Ever-present Good

Ken McLeod

Contents

Dedication

For Kilung Rinpoche

Epigraph

Go where there is no path

and leave no trail

Introduction

In 2003, I participated in a three-week retreat at Tara Mandala led by Dza Kilung Rinpoche. I went to the retreat with more than a little trepidation. Ever since I had left the three-year retreat center at Kagyu Ling in France in 1983, quite serious problems in mind and body would arise whenever I engaged in even moderately intensive practice.

Tsultrim Allione had invited me to the retreat and kindly lodged me in a lovely little cabin where I was on my own and could take care of myself. The cabin had a magnificent view overlooking the hills of southern Colorado. From the small balcony I could watch the sky, the play of clouds and the lightning that often flashed in the distance, and pursue meditation and practice as much as body and mind permitted. The walks up and down the hill, from the dining area to the teaching hall, provided me with plenty of exercise to counteract the tendency for energy to stagnate in my system. Kilung Rinpoche taught each morning from Longchenpas Ch-ying Dz (Tib. chos-dbyings rin-po-chei mdzod). For meditation instruction, he simply said to do nothing and left the rest up to us.

A bit to my surprise and much to my relief, my fears of recurrent problems were never realized. In this environment I was able to practice consistently without becoming ill for the first time in twenty years. That retreat started a process of unfolding experience that continues to this day.

At the end of the retreat, Kilung Rinpoche showed me a short text by the eighteenth-century Tibetan mystic Jigm Lingpa. The way he unwrapped the text and gave it to me told me more than words ever could that this text was dear to his heart. He said that he would be grateful if I could translate it into English. The text was a poem about the practice of dzogchen (great completion) and effectively summarized all that we had studied during the retreat. It was a bit difficult to understand in places, due largely to Jigm Lingpas style of writing, but with Gerardo Abbouds help, I translated it and presented the translation to Rinpoche. A few years later, I taught the text at a retreat in New Mexico. Now, encouraged by the response to my recent book Reflections on Silver River, I have retranslated that poem and written this commentary.

Over fifty years ago, D. T. Suzukis Essays in Zen Buddhisma compendium of anecdotes and sayings from the early Christian anchorites in the Egyptian deserts, set off reverberations with another chord. The common theme was a resonance with a certain kind of awareness a knowing that was vitally important to me, more important than what I did with my life.

Why did I and why do I pursue that knowing? In the end, it is simply because this knowing calls to me. In traditional Buddhism, this knowing is presented as nirvana, enlightenment, freedom, awakening, the end of suffering or any number of other promises. For me, those words now ring hollow. I think I believed them at one point, but I am not sure. The call of that knowing, however, has never been in doubt, and it still calls.

Spiritual Practice and Artistic Expression: An Analogy

While spiritual practice is not simply or even principally an aesthetic interest, I have found the analogy of artistic expression helpful in understanding the path I have taken, whether the expression is through painting, music or dance. When a musician learns to play an instrument or even a single piece of music, he or she begins a journey. No one knows or can know where that journey will lead. Maybe a teacher or a respected friend or colleague suggested that particular piece. Maybe the musician heard someone else play it and it moved something inside. What is important here is that he or she feels a call and is moved to respond. Whereas the call of music is usually to an aesthetic experience, the call of spiritual practice is to a different relationship with life itself. For me that calling took the form of a knowing, a knowing that was evident in the accounts of Buddhist masters, Christian mystics and, later, Sufi and Taoist sages.

Both art and spiritual practice have their own practice regimens. Art often involves long periods of rigorous training. Sometimes the training is even harsh, as in ballet and other forms of dance. Art also involves a kind of asceticism that is often similar to renunciation, a relationship with a teacher that may be hard to understand from a conventional perspective and a call to an ideal that is difficult, if not impossible, to put into words. From a utilitarian perspective, neither art nor spiritual practice produces something that is useful in the world. In fact, a use or the lack thereof is one of the criteria that Canadian customs officials use to determine whether an item is to be considered art. Today, there are innumerable explorations of the application of spiritual methods to conventional life (training in mindfulness, for example), and much research on the evolutionary origins of compassion and altruism, all with a view to helping us improve our lives and possibly improve the functioning of society. I have never felt that the purpose of either art or spiritual practice is to improve our lives in the conventional sense, or to make us healthier, better people or to help us be more successful, however one wants to define that pernicious notion.

Another analogy between art and spiritual practice is the matter of talent. I do not have much musical talent, but I once learned to play a couple of instruments passably. Even that took a lot of practice. I could not comprehend how some people could just pick up an instrument and play it and play it well. Equally amazing to me were those who could listen to a piece of music and not only play it but embellish or improvise from it. The same holds true in spiritual practice. Some people have to work long and hard just to be able to meditate at all. Other people seem to be able to meditate very easily. Still others seem to have a natural relationship with the subtle awareness that is the focus of many Buddhist practices. Understanding comes to them quickly. Nevertheless, people with natural talent do not necessarily have an easier time. They often have to work long and hard, too, both to realize the potential of their talent and to work through the difficulties and challenges it presents to them. Einstein, for instance, once wrote to a young girl, Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics. I can assure you mine are still greater.

Not infrequently, when a musician is mastering an instrument, that pursuit leads to unexpected difficulties. Similarly, the pursuit of the knowing that called to me led to difficulties that I could never have imagined. The challenges I faced over the years forced me to examine again and again what was I doing and why. Those re-examinations ruthlessly stripped away the ornate prose, the rich poetry, and the glowing accounts that abound in traditional texts.

All that remained was a profound simplicity that I saw running through all the sutras, the tantras, the commentaries and all the different methods of practice that have evolved over the centuries. This simplicity illuminates from within, making all the sutras and other writings transparent and clear. It is the genesis of the traditions and forms of practice that evolved in different countries and different cultures, and of the texts, rituals, ceremonies, worldviews, beliefs and other repositories of trust and faith. It is also what all those cultural artifacts are about. They both come from and point to this simplicity.