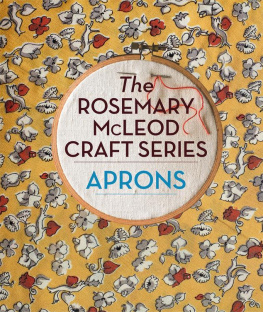

That book includes 47 projects, ranging from cushions and tea cosies to aprons and knitting projects. It is also rich with photographs of Rosemary McLeods collection of vintage craft and textiles, and of historical ephemera.

If there is such a thing as a natural stitcher, it cant be me. Just the same, I have for years hunted down and collected the early to mid-twentieth century domestic stitching handcrafts of women, the kind of home-made things I knew from my own family, and in the process I started making things myself.

I wrote my first textile book, Thrift to Fantasy, to explain what these things meant to me as a collector, and how they have meaning beyond the superficial; how they are stories in quiet counterpoint to the great world events and social change of their time.

The largely sidelined or forgotten domestic textile crafts knitting, embroidery, crochet, appliqu, felt work were carried out by ordinary women, wives and home-makers. Some were good knitters, others good dressmakers, while some excelled at embroidery. Some produced clumsy, resentful work, while others the saddest, surely made works of art they could never bear to use. Much was thrown away when they died, or wore out long before, and yet more stayed in the glory boxes it was stored in before they married, too good to use when they encountered real life.

When my mother died I kept the things that spoke to me about her, the things she had made with her own hands. Among these were the baby clothes she had knitted for me in fine white wool. I was professionally photographed in these regularly, as was the custom of the time.

I lived a life of textile luxury as a baby, in hand-smocked crpe de Chine dresses and lace-trimmed, pin-tucked petticoats. In my white wicker pram I lay under a white quilted satin cover, my head resting on lace-trimmed organdie pillows, while my family got by with few luxuries. Thats how important babies were after the slaughter of World War Two.

My mother used a treadle sewing machine. Every length of fabric she bought, and every button, was chosen with care; she literally could not afford to make mistakes. This is probably why, years after she died, I collected fabric lengths from the past. I liked the way they carried their time with them. Their colours and patterns flowers, abstract, figured, stripes, checks spoke of past design trends, and the aspirations of the women, like my mother, who had carried them home. I could hear her approving good quality, emphatically declaring them smart or, her fiercest condemnation, common! In this way I have accumulated a stash of period fabrics, which are what I like to use, and have used wherever possible for this book.

First contact

My first personal meeting with needles and thread was the gift of a toy sewing machine I hated on sight. At close quarters I disliked it even more, and before long it was put quietly away, a piece of snarled fabric wedged into it.

Then, at boarding school, art classes were replaced for a while, for juniors, with embroidery lessons. We would make samplers, the traditional way for little girls to learn the different stitches. Everyone else seemed to meekly make their needle and thread co-operate, but my sampler didnt get beyond the easiest stitches, and even they were stitched in a fury. Ive kept that tear-stained souvenir of mutiny because it holds potent memories. Id much rather have been drawing pictures.

I couldnt knit. My yarn tangled hopelessly. I hated dressmaking classes, too. Years later, with a child of my own, I finally made the connection that sewing was only drawing using different tools, and so I began to work out how to make things this way.

My mother had been a clever teacher. While she knitted, embroidered or sewed, she explained what she was doing and why, and though I only half listened, a lot came back to me: how to thread a needle, basic knitting stitches, how to hem a garment and mend my clothes, which fabrics were best for different purposes, how a piece of quality fabric felt in your hand. We had been poor, but we were not impressed by the cheap and nasty.

Womens magazines were a vital source of ideas in the 1930s to 1950s, and mine was a magazine-reading family. Favourites in my grandmothers household were the English Womans Weekly, Womans Own and Womans Realm. I read them all through my childhood.

I have since collected other popular titles that were common in New Zealand from the 1930s to the 1950s: Home, Wife and Home, Woman and Home, Britannia and Eve, My Home, the Womans Journal and others. They are long-extinct titles, but in their time they were arbiters of taste, a breath of distant England into colonial life.

Similar magazines were published in the United States, and I have collected those titles, too: The Modern Priscilla, McCall Needlework and Decorative Arts, Needlecraft. From Australia came New Idea, the Australian Home Journal, and other publications dedicated to textile craft, embroidery and knitting. There were few New Zealand titles, and those were likely to run patterns and designs sourced from overseas.

As their titles suggest, these magazines were devoted to domesticity, with feature articles on famous people and royalty, homespun advice on coping with life, sentimental verses, recipes, fashion, and romantic fiction. They published ideas for updating clothes when fabric was in short supply, or unobtainable in wartime, and advised on mending and decorating. In keeping with the thrifty virtues of the time, the women who bought these magazines often kept them until they died. Many of my copies have womens names pencilled on their covers by newsagents who held their orders 70 or more years ago.

More specialised magazines in wide circulation here were The Needlewoman, Needlewoman and Needlecraft, Pins and Needles, Good Needlework, Needlecraft and Stitchcraft. Some were subsidised by makers of threads and yarns. Along with providing free transfers, these publications invited women to send away small sums of money, which would have been Post Office money orders in those days, to buy transfers and kits to make the projects featured in their pages. The transfers still turn up regularly in thrift shops.

We shouldnt underestimate the importance of magazines before television came, when women couldnt easily enter other peoples homes and see how they lived. It was through magazines that they learned about fancy table settings, etiquette, dcor and fashion. They might have had limited incomes, but they could aspire to elegance, and be given the confidence to try something new.

In the less celebrity-driven time of the 1920s to the 1950s, womens magazines also offered the sense of being part of an international community at a time when women in New Zealand were unlikely to travel overseas in their lifetime.

These years encompassed great events, and their aftermath is still being played out today. Women lived through the great influenza epidemic, the aftermath of World War One, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and World War Two. It was a time of hardship for many, which called for the ingenuity featured in the books, womens magazines and craft publications of the time.

Incidentally there is inconsistency in the dating of these old magazines, which were often undated, dated erratically, or varied from year to year in the number of issues published. I have to rely on guesswork at times.

The Stash

Textile lovers know what is meant by The Stash: the hoard of fabrics and sewing paraphernalia that we keep in anticipation of future projects.