About the authors

Graham Lawton

After a degree in biochemistry and an MSc in science communication, both from Imperial College, Graham Lawton landed at New Scientist , where he has been for almost all of the twenty-first century, first as features editor and now as executive editor. His writing and editing have won a number of awards.

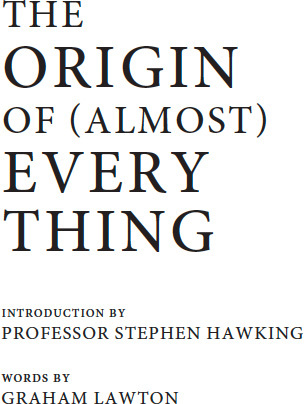

Stephen Hawking

Stephen Hawking is the former Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and author of A Brief History of Time which was an international bestseller. He is now the Dennis Stanton Avery and Sally Tsui Wong-Avery Director of Research at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics and Founder of the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology at Cambridge.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK company

First published in USA in 2016 by Nicholas Brealey Publishing

This edition first published in 2018

Copyright New Scientist 2016

The right of New Scientist to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

John Murray, UK

ISBN 978 1 473 62926 4

Nicholas Brealey Publishing, US

ISBN 978 1 857 88939 0

Additional writing by Sally Adee, Gilead Amit, Colin Barras, Alison George, Joshua Howgego, Justin Mullins, Mick OHare and Richard Webb

Fact checking by Chris Simms

Copy editor: Hilary Hammond

Proof readers: Miren Lopategui and Margaret Gilbey

Indexer: Caroline Wilding

John Murray (Publishers)

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

Nicholas Brealey Publishing, US

Hachette Book Group

Market Place Center, 53 State Street

Boston, MA 02109 USA

www.johnmurray.co.uk

www.nicholasbrealey.com

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Professor Stephen Hawking

E XISTENCE: WHERE DID WE COME FROM? Why are we here? According to the Boshongo people of central Africa, before us there was only darkness, water and the great god Bumba. One day Bumba, in pain from a stomach ache, vomited up the Sun. The Sun evaporated some of the water, leaving land. Still in discomfort, Bumba vomited up the Moon, the stars and then the leopard, the crocodile, the turtle and, finally, humans.

This creation myth, like many others, wrestles with the kinds of questions that we all still ask today. Fortunately, as will become clear, we now have a tool to provide the answers: science.

When it comes to these mysteries of existence, the first scientific evidence was discovered in the 1920s, when Edwin Hubble began to make observations with a telescope on Mount Wilson in California. To his surprise, Hubble found that nearly all the galaxies were moving away from us. Moreover, the more distant the galaxies, the faster they were moving away. The expansion of the universe was one of the most important discoveries of all time.

This finding transformed the debate about whether the universe had a beginning. If galaxies are moving apart at the present time, they must therefore have been closer together in the past. If their speed had been constant, then they would all have been on top of one another billions of years ago. Was this how the universe began?

At that time many scientists were unhappy with the universe having a beginning because it seemed to imply that physics had broken down. One would have to invoke an outside agency, which for convenience one can call god, to determine how the universe began. They therefore advanced theories in which the universe was expanding at the present time but didnt have a beginning.

Perhaps the best known was proposed in 1948. It was called the steady state theory, and it suggested that the universe had existed for ever and would have looked the same at all times. This last property had the great virtue of being a prediction that could be tested, a critical ingredient of the scientific method. And it was found lacking.

Observational evidence to confirm the idea that the universe had a very dense beginning came in October 1965, with the discovery of a faint background of microwaves throughout space. The only reasonable interpretation is that this cosmic microwave background is radiation left over from an early hot and dense state. As the universe expanded, the radiation cooled until it became just the remnant we see today.

Theory soon backed up this idea. With Roger Penrose of Oxford University, I showed that if Einsteins general theory of relativity is correct, then there would be a singularity, a point of infinite density and spacetime curvature, where time has a beginning.

The universe started off in the Big Bang and expanded quickly. This is called inflation and it was extremely rapid: the universe doubled in size many times in a tiny fraction of a second.

Inflation made the universe very large, very smooth and very flat. However, it was not completely smooth: there were tiny variations from place to place. These variations eventually gave rise to galaxies, stars and solar systems.

We owe our existence to these variations. If the early universe had been completely smooth, there would be no stars and so life could not have developed. We are the product of primordial quantum fluctuations.

As will become clear, many huge mysteries remain. Still, we are steadily edging closer to answering the age-old questions: Where did we come from? And are we the only beings in the universe who can ask these questions?

PREFACE

Graham Lawton

I HAVE ALWAYS BEEN FASCINATED BY ORIGINS. As a child, I used to go out to the Yorkshire coast with my mum, dad and sister; wed dig ammonites, belemnites and devils toenails out of the cliffs and Id wonder: Where did they come from? What was the Earth like when they were alive?

It wasnt just the natural world that made me ask where things came from. I remember watching the television probably black and white in those days, but still a technological wonder and thinking: Who invented that? I couldnt fathom how somebody could have created a box with a screen that projected pictures from far away. Left to my own devices, I thought, I could never have done that.

When I became a science journalist 20 years ago, I realised the powerful pull that origin stories exert on our imaginations. Where did we come from? is one of the most profound and fundamental questions we ask ourselves. (The others are How should we live? and Where are we going?, but those are for another day.) I am convinced it is part of human nature to look at something, or ponder some existential question, and say: How did that come to be?

Every society we know of has stories about the origin of the cosmos and its inhabitants. The oldest creation myth on record is the Enuma Elish, written on 2,700-year-old clay tablets and dating from Bronze Age Babylon. But origin stories surely long pre-date that, dating to at least 40,000 years ago when our ancestors became what is known as behaviourally modern humans. To the best of our knowledge, their minds were identical to ours. That means they possessed the capacity for mental time travel the ability to project themselves into the past and future, allowing our ancestors to transcend the here and now and even the bookends of their own lifetimes to contemplate the deep past and the distant future. They must, like us, have wondered where it all came from.