Preface

In a way, I began working on this book as an undergraduate, long before I had even heard of the Deobandis. I think I can even pinpoint a specific moment: reading Bruce Lawrences Defenders of God for a seminar paper on fundamentalism and modernity. Even more precisely, I remember being captivated by a single idea from that book: that fundamentalists are moderns but they are not modernists. Since then, the social-scientific category of fundamentalism has lost much of its cachet, giving way to newer and more dynamic approaches to understanding religion and politics. But the idea that movements that define themselves against the modern are irrevocably (though never monolithically) shaped by modernity has continued to fascinate me. This idea is, by no means, some sort of skeleton key that unlocks the truth about movements like the one I describe in this book. On the contrary, this book argues that modernity, as an analytical lens, has certain limitations. Regardless, for me, the idea has been a generative one.

To the extent that my thinking about this topic began in college, it seems appropriate to start there in marking the profound intellectual debts I have built up over the years. At Reed College, R. Michael Feener introduced me to the study of Islam, and Kambiz GhaneaBassiri and Steven Wasserstrom cemented that interest. The formidable theory and method in religious studies courses I took with Arthur McCalla have stuck with me. Even today, I still think majoring in religion at Reed was probably the single most intellectually consequential decision I ever made.

At the University of North Carolina, the (literally) once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study with a cluster of scholars in the TriangleCarl W. Ernst, Bruce Lawrence, Ebrahim Moosa, Omid Safishaped my interest in Sufism, Islamic law, and South Asia. I thank Ebrahim for sharing with me his intimate knowledge of madrasa culture and South Africa, and for being a consistently reliable resource as this project has developed. Above all, I thank Carl for supervising the dissertation on which this book is based. He did far more than supervise a dissertation, of course. Carl modeled (and continues to model) what ethically engaged, public-facing scholarship looks like. If I can identify a specific moment when my interest in the Deobandis began, it would be when Carl lent me his personal copy of Rashid Ahmad Gangohis fatwas (which, I will note for my colleagues who were at the October 2017 conference in honor of Carl, I have returned, at long last).

I did research for this book on three continents (Asia, Africa, and Europe). It would not have been possible without the help and assistance of numerous people. Waris Mazhari opened doors for me in Deoband and Delhi. Ashraf Dockrat and Ismail Mangera opened them in Johannesburg. Akmed Mukaddam and Abdulkader Tayob put me in touch with key interlocutors in Cape Town. Throughout my stay in South Africa, Abdulkader and the Centre for Contemporary Islam at the University of Cape Town gave me invaluable institutional support. The archival work on which the final two chapters rely could not have been done without the help of the librarians of the National Library of South Africa branches in Pretoria and Cape Town, the Documentation Centre at the University of Durban-Westville, and the University of Cape Towns African Studies Library. I would also like to extend my gratitude to McGill Universitys librarians for indulging my incessant digitization requests for materials from their Islamic Studies Library.

Revising the dissertation was nurtured in the supportive community I have been so fortunate to have at Northwestern University. I want to thank my colleagues in the Department of Religious Studies who have read, patiently listened to, and commented on bits and pieces of the book over the years. A number of my colleagues, in Religious Studies and beyond, read the book in its entirety: Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, Sylvester Johnson, Richard Kieckhefer, and Rajeev Kinra. I thank them all for their generosity. But I want to single out Beth Hurd, with whom I codirect a Buffett Institute research group, Global Politics and Religion. This book has benefitted in countless ways from my conversations with her and with the scholars we have hosted.

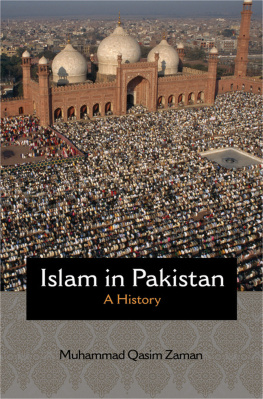

Beyond Northwestern, two scholars deserve extra special thanks. First, Muzaffar Alam read a draft of the book and then devoted almost an entire day to sitting with me in his office, giving me copious notes in a way that only he can: orally, quite nearly from memory, and with reference to relatively obscure late-colonial texts that most Mughal historians have probably not heard of, let alone read. Second, Muhammad Qasim Zaman also read a draft and was exceptionally generous with his criticisms and suggestions, drawing on his peerless knowledge of the ulama. Its no exaggeration to say that every conversation Ive been lucky to have had with Qasim over the years yielded new epiphanies. I am in his debt.

Along the way, I have benefited from presenting chapters in progress at a variety of workshops and conferences. I presented chapter 1 at the University of Leipzig workshop Muslim Secularities: Explorations into Concepts of Distinction and Practices of Differentiation, a version of which is forthcoming in a special issue of Historical-Social Research . I thank the two anonymous readers for their valuable comments. I presented chapter 3 at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, and parts of chapter 4 at the University of Chicago workshop Inhabiting Pasts in Twentieth Century South Asia. I thank the conveners of these workshops, respectively: Markus Dressler, Armando Salvatore, and Monika Wohlrab-Sahr; Margrit Pernau; and Daniel Morgan and Fareeha Zaman. I also presented bits of the book at multiple American Academy of Religion and Annual Conference on South Asia meetings, too many to list, and my gratitude goes out to all my colleagues who have heard my papers over the years and given me feedback, many of whom I name below.