MacIntyre - After virtue: a study in moral theory

Here you can read online MacIntyre - After virtue: a study in moral theory full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: University of Notre Dame Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

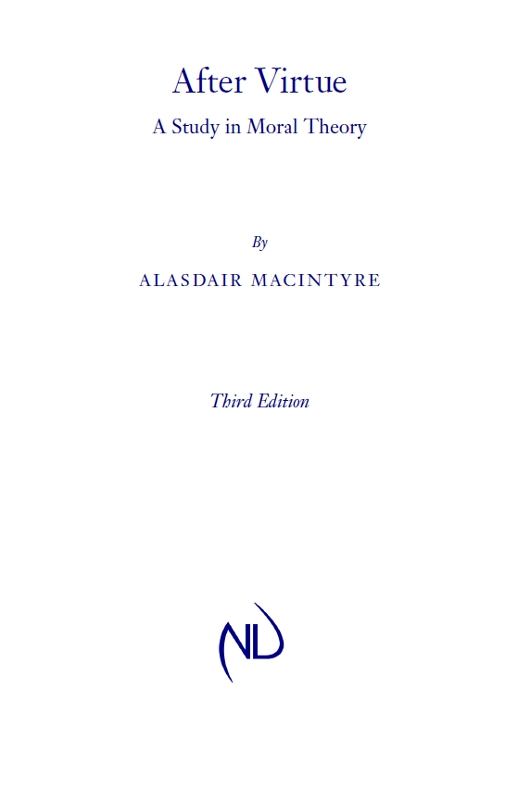

- Book:After virtue: a study in moral theory

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Notre Dame Press

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

After virtue: a study in moral theory: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "After virtue: a study in moral theory" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

After virtue: a study in moral theory — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "After virtue: a study in moral theory" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

After Virtue

A Study in Moral Theory

By

ALASDAIR MACINTYRE

Third Edition

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

Third edition published in the United States in 2007

by the University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

www.undpress.nd.edu

All Rights Reserved

Copyright 1981, 1984, 2007 by Alasdair MacIntyre

E-ISBN: 978-0-268-08692-3

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at

TO THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER AND HIS SISTERS AND BROTHERS

Gus am bris an la

Contents

After Virtue after a Quarter of a Century

If there are good reasons to reject the central theses of After Virtue, by now I should certainly have learned what they are. Critical and constructive discussion in a wide range of languagesnot only English, Danish, Polish, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Italian, and Turkish, but also Chinese and Japaneseand from a wide range of standpoints has enabled me to reconsider and to extend the enquiries that I began in After Virtue (1981) and continued in Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988), Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990), and Dependent Rational Animals (1999), but I have as yet found no reason for abandoning the major contentions of After VirtueUnteachable obstinacy! some will sayalthough I have learned a great deal and supplemented and revised my theses and arguments accordingly.

Central to these was and is the claim that it is only possible to understand the dominant moral culture of advanced modernity adequately from a standpoint external to that culture. That culture has continued to be one of unresolved and apparently unresolvable moral and other disagreements in which the evaluative and normative utterances of the contending parties present a problem of interpretation. For on the one hand they seem to presuppose a reference to some shared impersonal standard in virtue of which at most one of those contending parties can be in the right, and yet on the other the poverty of the arguments adduced in support of their assertions and the characteristically shrill, and assertive and expressive mode in which they are uttered suggest strongly that there is no such standard. My explanation was and is that the precepts that are thus uttered were once at home in, and intelligible in terms of, a context of practical beliefs and of supporting habits of thought, feeling, and action, a context that has since been lost, a context in which moral judgments were understood as governed by impersonal standards justified by a shared conception of the human good. Deprived of that context and of that justification, as a result of disruptive and transformative social and moral changes in the late middle ages and the early modern world, moral rules and precepts had to be understood in a new way and assigned some new status, authority, and justification. It became the task of the moral philosophers of the European Enlightenment from the eighteenth century onwards to provide just such an understanding. But what those philosophers in fact provided were several rival and incompatible accounts, utilitarians competing with Kantians and both with contractarians, so that moral judgments, as they had now come to be understood, became essentially contestable, expressive of the attitudes and feelings of those who uttered them, yet still uttered as if there was some impersonal standard by which moral disagreements might be rationally resolved. And from the outset such disagreements concerned not only the justification, but also the content of morality.

This salient characteristic of the moral culture of modernity has not changed. And I remain equally committed to the thesis that it is only from the standpoint of a very different tradition, one whose beliefs and presuppositions were articulated in their classical form by Aristotle, that we can understand both the genesis and the predicament of moral modernity. It is important to note that I am not claiming that Aristotelian moral theory is able to exhibit its rational superiority in terms that would be acceptable to the protagonists of the dominant post-Enlightenment moral philosophies, so that in theoretical contests in the arenas of modernity, Aristotelians might be able to defeat Kantians, utilitarians, and contractarians. Not only is this evidently not so, but in those same arenas Aristotelianism is bound to appear and does appear as just one more type of moral theory, one whose protagonists have as much and as little hope of defeating their rivals as do utilitarians, Kantians, or contractarians.

What then was I and am I claiming? That from the standpoint of an ongoing way of life informed by and expressed through Aristotelian concepts it is possible to understand what the predicament of moral modernity is and why the culture of moral modernity lacks the resources to proceed farther with its own moral enquiries, so that sterility and frustration are bound to afflict those unable to extricate themselves from those predicaments. What I now understand much better than I did twenty-five years ago is the nature of the relevant Aristotelian commitments, and this in at least two ways.

When I wrote After Virtue, I was already an Aristotelian, but not yet a Thomist, something made plain in my account of Aquinas at the end of . I became a Thomist after writing After Virtue in part because I became convinced that Aquinas was in some respects a better Aristotelian than Aristotle, that not only was he an excellent interpreter of Aristotles texts, but that he had been able to extend and deepen both Aristotles metaphysical and his moral enquiries. And this altered my standpoint in at least three ways. In After Virtue I had tried to present the case for a broadly Aristotelian account of the virtues without making use of or appeal to what I called Aristotles metaphysical biology. And I was of course right in rejecting most of that biology. But I had now learned from Aquinas that my attempt to provide an account of the human good purely in social terms, in terms of practices, traditions, and the narrative unity of human lives, was bound to be inadequate until I had provided it with a metaphysical grounding. It is only because human beings have an end towards which they are directed by reason of their specific nature, that practices, traditions, and the like are able to function as they do. So I discovered that I had, without realizing it, presupposed the truth of something very close to the account of the concept of good that Aquinas gives in question 5 in the first part of the Summa Theologiae.

What I also came to recognize was that my conception of human beings as virtuous or vicious needed not only a metaphysical, but also a biological grounding, although not an especially Aristotelian one. This I provided a good deal later in Dependent Rational Animals, where I argued that the moral significance of the animality of human beings, of rational animals, can only be understood if our kinship to some species of not yet rational animals, including dolphins, is recognized. And in the same book I was also able to give a better account of the content of the virtues by identifying what I called the virtues of acknowledged dependence. In so doing I drew on Aquinass discussion of misericordia, a discussion in which Aquinas is more at odds with Aristotle than he himself realized.

These developments in my thought were the outcome of reflection on Aquinass texts and on commentary on those texts by contemporary Thomistic writers. A very different set of developments was due to the stimulus of criticisms of

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «After virtue: a study in moral theory»

Look at similar books to After virtue: a study in moral theory. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book After virtue: a study in moral theory and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.