Gaza

A brilliant and incisive account of this tiny, vibrant, but embattled enclave. With the two million people of Gaza struggling to survive food shortages, electricity cuts, and increasing amounts of sewage in her surrounding seas, this is a must-read.

Jon Snow

Donald Macintyres Gaza is a deeply informed and elegant portrait of this small but profoundly important and misunderstood part of the world. Not only are Gazas history and politics made compellingly accessible, so too are her sight, sound and smell. In this way Macintyre challenges any notion of Gazas irrelevance and perhaps more importantly does what few authors writing on Gaza have done: elevates the ordinary in a manner that will endure, helping the reader understand that no matter who we are and where we are from, in Gaza we can recognise ourselves. This book speaks to something greater than Gazas pain; it speaks to Gazas soul.

Sara Roy, Senior Research Scholar,

Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University

Donald Macintyre has written a remarkable political panorama about Gaza today. In cool prose he exposes the history of the conflict and the discussion that has surrounded it. Anyone interested in understanding the situation between Hamas, the Palestinian Authority and Israel should look at the conclusion of this book. Anyone who wants to feel a little bit how people live in this narrow strip of land on the Mediterranean coast must read the whole work.

Shlomo Sand, Professor of History, Tel Aviv University,

and author of The Invention of the Jewish People

Contents

Prologue: Shakespeare in Gaza

Leyla abdul rahim had come to the line in Act IV of King Lear where the blinded Gloucester laments, As flies to wanton boys are we to th gods. They kill us for their sport. Or, rather, the paraphrase offered in the textbook English for Palestine : We are like flies and the gods are like cruel little boys. They torment us and kill us for fun. The teacher described children pulling the wings off a fly. So the gods torment us for fun, to laugh, to play, okay? she said, quickly adding: This is not related to our religion. It is away from our Islam. Allah doesnt torment us, of course.

It was tempting to point out from the back of the class that God isnt supposed to do that in other monotheistic religions either. But that would have been an abuse of Mrs Abdul Rahims generous invitation to sit in on her Grade 12 English class at Bashir al-Rayyes High School for Girls in Gaza City. And the thirty students preparing for the tawjihi , the high school matriculation, for which King Lear was a set text were enjoying themselves. Hands shot up and there were repeated cries of Miss, Miss whenever Mrs Abdul Rahim tested her seventeen-year-old charges, all but one in the standard uniform of pale blue smock, jeans and white headscarf. Goneril is now in love with Edmund. Hes evil. Hes like her exactly. Do you think Goneril respects her husband? (Chorus of no.)

When Mrs Abdul Rahim ended the lesson, the girls burst spontaneously into applause. After the class, Khulud al-Masharawi said in English that she liked the play because Lear began to feel sorry for people other than himself. He thought about people who had no home, or are on their own.

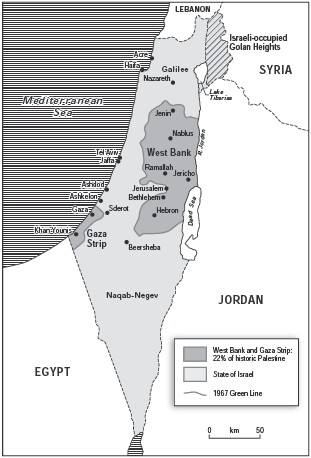

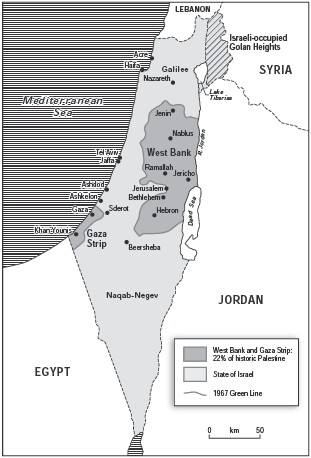

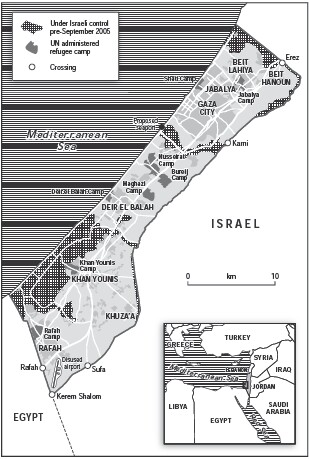

It took a moment to remember that this classroom tour de force had taken place in an isolated, overcrowded 140-square-mile strip of territory corralled by concrete walls and electronically monitored fences, ruled by an armed and proscribed Islamic faction, and succinctly described in recent memory by Condoleezza Rice as a terrorist wasteland. Gaza, as often, was failing to conform to its stereotype.

I had been brought to the Lear class by another English teacher, Jehan al-Okka. It was fair-minded of her, because she harboured doubts about the suitability for Gaza schoolgirls of Shakespeares tragedies, a sentiment clearly not shared by her colleague. For Jehan, Lear was at least an improvement on Romeo and Juliet . She had been among a group of Gaza teachers who staged a successful mini-uprising against a decision to include Romeo and Juliet in that years English curriculum for the tawjihi . (Despite the schism between Hamas and the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Authority since Hamass seizure of control in June 2007, the PA continued to supervise the syllabus from its Ramallah base for Gaza as well as the West Bank.) Jehan was convinced that Romeo and Juliet was the wrong play at the wrong time. It encourages suicide and disobeying parents, she said. Jehan was also concerned that some of her pupils, upon learning that they were to study the play, had downloaded the film version; more, she thought, for the immoral scenes rather than any educational purpose. She was relaxed about university students studying the play but felt it was unsuitable for impressionable teenagers.

As it happened, Romeo and Juliet had been part of the high school syllabus from the years when Gaza had been under Egyptian control and then after the Six Day War and Israeli conquest in 1967. But Jehan, who wasnt in Hamas, saw a contradiction between Islamic culture and the things that Shakespeare is trying to convey in his tragedies. She spoke of the conditions in Gaza: the ten-year Israeli blockade crippling Gazas economy which, she believed, had led to a rise in crime. Im not saying King Lear is encouraging it, but we are trying to reduce violence in our country. And for people who have psychological problems this makes it looks glamorous... When she was teaching Lear she said she was careful to warn her pupils: this is not in our culture. None of you will do this.

Despite her doubts, Jehan took pride in the conscientiousness with which she taught the play. And she was popular. Abir, one seventeen-year-old in the science stream class Jehan took for English, gently defied her teacher by saying she wouldnt mind studying Romeo and Juliet instead of Lear . When we discussed the right age to get married, none of the girls wanted to do so before their twenties, despite the tradition of early marriage prevalent in some sections of Gaza society. But the independent-minded Abir suggested the highest age of all: twenty-eight. Jehan explained that some two-thirds of science stream pupils wanted to be doctors Its a dream, she said. But Abir wanted to be an engineer. Were there many women engineers in Gaza? Yes, many, the teacher said crisply, without jobs. Unemployed.

Back in the principals office we returned to the subject of the English set text. Why give the students something that is full of misery? she asked. The students, when someone dies they are all like, why is he doing this, the writer? Everyone dies by the end and the lovely Cordelia dies. Some of the students cried when I said Cordelia died. When I studied at university I was old enough to understand the value. For children, when they read something they take the image killing, suicide, treason. And life in Gaza is bad enough not to increase that misery.

This was the most challenging of Jehans points. She was right, for example, that suicide among young Gazans seemed to be on the rise. Are there societies so under pressure that they cannot safely absorb Shakespearean tragedy?

Whatever Jehans concerns, the prevailing Gaza answer to that question appeared to be no. At Gaza Citys al-Mishal Cultural Centre, a staged version of Romeo and Juliet ran to appreciative audiences for eight nights in early May 2016. The prominent Gaza writer Atef Abu Saif and the director Ali Abu Yassin had set the play in modern Gaza with the star-crossed lovers Yousef and Suha belonging to each of the main rival Palestinian factions Hamas and Fatah, instead of to the Montagues and Capulets. It opened in a caf where a clean-shaven Fatah doctor and a bearded Hamas businessman fall into an argument until they are thrown out by the owner. The caf owner represented the Gazan everyman, enraged by the split between the two factions that has deformed Palestinian politics since 2007.

Next page