PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published in Penguin Books 2013

Copyright Keeping Kids Company Limited, 2013

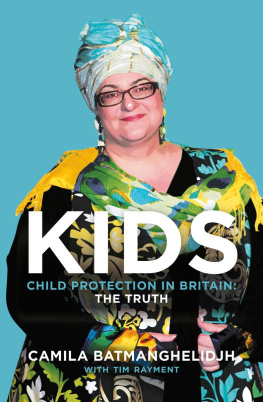

Cover image: Nathalie Murphy, Cover design: Jim Stoddart, Author photo: Jochen Braun.

All rights reserved

The moral right of the authors has been asserted

ISBN: 978-1-84-614656-5

| Camila Batmanghelidjh and Kids Company | Mind the Child

The Victoria Line |

| Danny Dorling | The 32 Stops

The Central Line |

| Fantastic Man | Buttoned-Up

The East London Line |

| John Lanchester | What We Talk About When We Talk About The Tube

The District Line |

| William Leith | A Northern Line Minute

The Northern Line |

| Richard Mabey | A Good Parcel of English Soil

The Metropolitan Line |

| Paul Morley | Earthbound

The Bakerloo Line |

| John OFarrell | A History of Capitalism According to the Jubilee Line

The Jubilee Line |

| Philippe Parreno | Drift

The Hammersmith & City Line |

| Leanne Shapton | WaterlooCity, CityWaterloo

The Waterloo & City Line |

| Lucy Wadham | Heads and Straights

The Circle Line |

| Peter York | The Blue Riband

The Piccadilly Line |

Camila

I have an ambivalent attitude towards the Underground. I recognize that it serves a lot of people, delivering them to their destinations. But for me, it sadly acquired an alternative fascination. When I was fourteen, my sister jumped in front of a train. Luckily, she fell into a hollow in between the tracks, so although the train did go over her and injured her leg, she survived. I called it the thirty-pence suicide attempt because that was the cost of her ticket, a pink slip of paper that I have kept to this day. I often wonder about the shock the driver must have experienced, and how horrific the event was for him as well as for my sister, who had to be carefully rescued from beneath the train.

Since then, each time someone jumps on the tracks, bringing the station to a halt, I find myself preoccupied with the discrepant journeys we all take in life: the parallel existences of the destination-driven crowd, who move rapidly to complete a life task, and the destination-despondent, who decide that life is no longer worth pursuing.

Subsequently, my sister did commit suicide, but before that, when I was nine years old and living in Iran, I had very clearly decided to take up a commitment to work with disadvantaged children. My own childhood was sheltered, as was my sisters. We had enormous access to opportunities and rich experiences afforded by the wealthy environments we were born to. When I was fourteen and she was twenty-five, our lives turned upside down because of the Iranian revolution. My father, who had made his money legitimately, did not run away, and as one of the most well-known men in Iran he was captured by the revolutionary forces and imprisoned in Evin, the high-security prison. Every day, we lived with the fear and uncertainty that he would be or had been executed. Sometimes pictures of bodies on mortuary tables were sent to us, suggesting that he was among the dead. As communications were ruptured, the fantasy of what might be happening to him drove my sister to her death.

Even though her loss was deeply traumatic, it wasnt personal trauma that compelled me to work with children it was a love of serving others. I can feel you rolling your eyes, thinking What kind of a fruitcake is this? I recognize that some people may perceive those who want to help as wounded healers, compensating for personal vulnerabilities. However, some of the worlds richest cultures put care-giving at the forefront of their agenda, and see it as an expression of refinement rather than failure or weakness.

I had two grandfathers: one was a self-made multi-millionaire by twenty-one, and went on to generate extraordinary personal wealth; the other was financially poor, but dedicated his life to healing children. I recollect people queuing up in the street to bring their children to him for medical treatment. There was something beautiful about him: he was understated and graceful, and I could see something of his spirit hovering a dance in the air, as if compassion was making him high.

I could best be described as an odd child. Having been born very premature (two and a half months early, weighing 1kg), I wasnt put in an incubator because they thought I was going to die anyway, so I think I spent a lot of time in an abstract space between life and death. I recollect being very sensitive to atmospheres, and to people beyond their visible skins. As I travelled in our police-protected car, I used to look out of the window and notice children on the streets selling matchboxes. It wasnt long before I realized the discrepancy between our worlds, and the lack of material possibilities in other childrens lives. I started taking food from our house and leaving it outside the doors of poor people so that they could feed their children. I didnt want anyone to know that I had done it, because I didnt want anyone to feel grateful. (The rest of the time I delighted in attempting to fly in our garden, and to this day I am sure that through flapping my arms I did lift off the ground!)

So my preoccupation with children of other lives began very early. My mother bemusedly agreed to provide me with a subscription to a psychological magazine about childhood development, which would arrive every Wednesday. I would hug it and climb into bed with it, determined to read every article from beginning to end. It was as if I was born with an instinct, for which I sought words and definitions. In my twenties I completed a psychotherapy course, and embarked on a career meeting some of the wonderful children whose voices will be heard in this book.