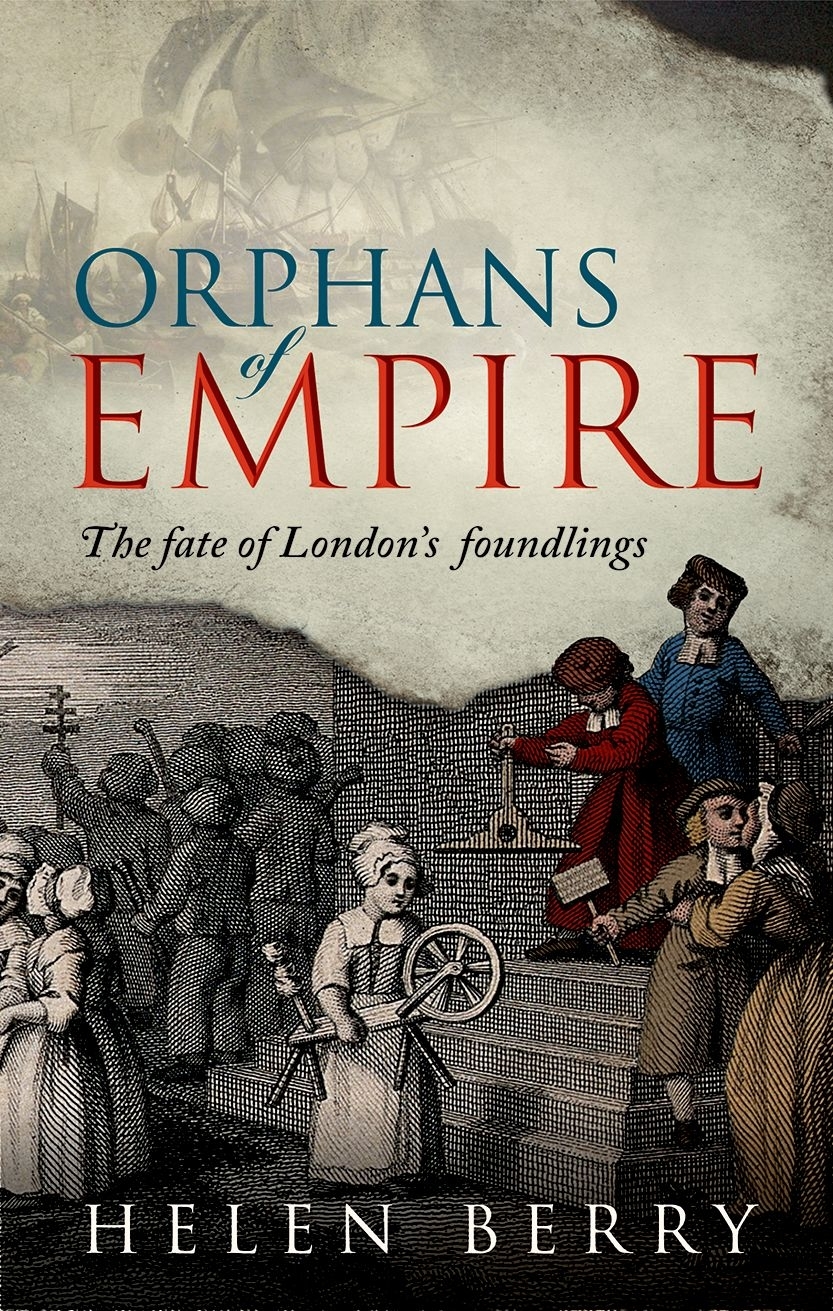

Orphans of Empire

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark ofOxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Helen Berry 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018950679

ISBN 9780198758488

ebook ISBN 9780191076121

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

This book is dedicated to

Mary Bamsey

(19142014)

and to the mothers of lost children everywhere

Preface

At Russell Square tube station in central London, throngs of tourists gather daily, straight from their hotel breakfasts or discharged from long-distance coaches, and move off in packs towards Covent Garden. If they only took a moment and headed north-east in the opposite direction, they would find instead a much quieter corner, a seven-acre park known as Corams Fields just a few streets away. If it is a fine day, there will be the sound of children playing. The observant eye may spot a curious sign (Adults may only enter if accompanied by a child). This green playground, with its childrens centre, nursery, and city farm, was once the site of the London Foundling Hospital. It was built upon fifty-six acres of land in Lambs Conduit Fields, purchased for the princely sum of 7000 in 1742 from the earl of Salisbury. All that survives today is a small colonnade, since the rest of the building was demolished in the 1920s. Nearby is the Foundling Museum, where the interior of some of the original Hospital has been preserved, complete with the valuable art work that was donated by famous artists of the day. Here in the Museum it is possible to stand in the reconstructed room, replete with fine wooden panelling and moulded ceiling, where poverty-stricken mothers brought their infants in a desperate attempt to have them admitted to the Hospital. The spectacle of their misery has been imagined by countless visitors, recreating the public drama that was described by Georgian commentators in vivid detail.

This book relates the history of what happened to those infants who gained admission by chance to the London Foundling Hospital, and who survived long enough to go out into the wider world. Their stories are set within the context of Britains imperial history from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, exploring the social, economic, and political forces that were behind the establishment and funding of the Hospitals mission during the first 100 years of its existence. This is not a history of empire as told by military historians, but it explores instead the ways in which British imperial ambitions abroad shaped society at home. It reveals how empire shaped the fortunes and life chances of the very poorest members of society. This book sets out to explore how the dynamics of political, cultural, and economic forces shaped Georgian society, particularly in relation to maritime trade and warfare, and the interconnections between the charitable deeds and interests of the governing elite and the fortunes of the poor. It explores what living in London, the great metropolis at the centre of what was rapidly becoming the worlds leading superpower, meant for poor children at the mercy of charitable institutions. The eighteenth century witnessed new experiments in social welfare sponsored by the ruling elite through a combination of charity and direct government investment, among which the London Foundling Hospital was one of the most expensive and ambitious schemes. The Hospital was a voluntary response to the growing problem of urban poverty, an unprecedented venture for the English that had consequences, intended and unintended, not just in London but throughout the nation for all concerned in the enterprise. Its influence extended globally in the pattern of the philanthropy it modelled among the rich and powerful, and among working communities in the life courses of the children it raised. Understanding this phenomenon will require a certain amount of openness to rethinking the motivation on the part of those who sought to do good in their own time, and a nuanced understanding of the complicated motivations for people to engage in charitable works, both in the eighteenth century and today.

The sources of evidence relating to those whose lives depended upon charity are extremely difficult to piece together in the archives. First-hand accounts written by societys poorest members who often had little or no literacy are almost non-existent, so the fragments that document their lives are usually mediated through others: the accounts of clerks, court scribes, and commentators. The voices of orphaned and abandoned children are very difficult to hear in modern times: recovering them from almost 300 years ago is almost but not quite impossible. The history of George King, a former foundling who wrote a detailed autobiographical account of his life, is woven through the narrative of this book, a single, precious thread. Other foundling voices join his in smaller, broken whispers. Together, they tell the story of what it was like to be raised without knowing the name you were given at birth, nor the identity of your parents, during the century before Queen Victoria came to the throne.

Contents

Whether tis Nobler in the minde to suffer

The Slings and Arrowes of outragious Fortune,

Or to take Armes against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet (first fol., 1623),

Act III, Scene 1

The public opening of Trafalgar Square, one of Londons most famous landmarks, on 1 May 1844 was not a great success. Building work had begun as far back as the 1820s to clear and develop the site, which was formerly occupied by the Royal Mews. The outlandishly extravagant monarch George IV had his horses moved to Buckingham Palace, leaving the premises empty, but progress on developing the site over the next two decades was slow. The leading architect of Regency style, John Nash, developed the south side of the square, but he died in 1835 before the work was completed. It was then decided that the square would be named after the Battle of Trafalgar in commemoration of Admiral Lord Nelsons famous victory in October 1805. Plans for the new National Gallery on the north side were criticized for their lack of grandeur, whose architect William Wilkins also died before the work could be completed. By the 1840s a new architect, Charles Barry, had been appointed, and the scheme became more costly and grandiose, with the addition of fountains, four granite plinths for sculptures, and pedestals for lighting. An extra committee was formed to commission a monument to Nelson, who had died a heros death at Trafalgar, but it took two years for them to decide how public subscriptions towards the cost of the monument could best be organized and managed. Eventually, an open competition was held. It was won by the architect William Railton, who produced a design for a monumental column topped by a statue of Nelson and flanked by four bronze lions. Charles Barry publicly declared his dislike of the winning scheme, and there was further widespread condemnation. The famous Trafalgar Square statues of lions by Sir Edward Landseer were not finished until the 1860s. Further delay this time was caused by Landseers insistence on sketching from a real lions corpse obtained from London Zoo, which decomposed before the artist had time to finish his drawings.