The

Essential

Kabbalah

The Heart

Of Jewish

Mysticism

Daniel C. Matt

For Ana

On her tongue, a Torah of love

PROVERBS 31:26

Contents

K ABBALAH, the Jewish mystical tradition, is precious and well hidden. Its symbolism, allusions, and multiple layers of meaning have attracted and confounded readers for centuries. Having studied Kabbalah for some twenty-five years, my attraction has not abated; my confoundedness has not been eliminated, but seasoned by wonder.

In this book I offer a selection of what I consider to be essential teachings from the immense trove of Kabbalah. I have translated the passages from the original Hebrew and Aramaic texts, and supplied notes to guide you through the maze. The introduction traces the history of Kabbalah and explains its salient concepts and symbols. A brief bibliography suggests titles for further study. In rendering the passages from Kabbalah into English, I have at times omitted material. I have taken the liberty of not indicating these omissions with ellipses, so as not to interrupt the flow of the translation. Precise citations are provided in the notes, so that interested readers can refer back to the original.

A number of friends and colleagues have been kind enough to offer advice or read parts of the manuscript. I would like to thank Arnold Eisen, Moshe Idel, Yehuda Liebes, Ehud Luz, and Elliot Wolfson. I am grateful to John Loudon, executive editor at Harper San Francisco, for inviting me to compose this book and for encouraging me along the way.

T HE H EBREW word kabbalah means receiving or that which has been received. On the one hand, Kabbalah refers to tradition, ancient wisdom received and treasured from the past. On the other hand, if one is truly receptive, wisdom appears spontaneously, unprecedented, taking you by surprise.

The Jewish mystical tradition combines both of these elements. Its vocabulary teems with what the Zoharthe canonical text of the Kabbalahcalls new-ancient words. Many of its formulations derive from traditional sourcesthe Bible and rabbinic literaturebut with a twist. For example, the world that is coming, a traditional phrase often understood as referring to a far-off messianic era, turns into the world that is constantly coming, constantly flowing, a timeless dimension of reality available right here and now, if one is receptive.

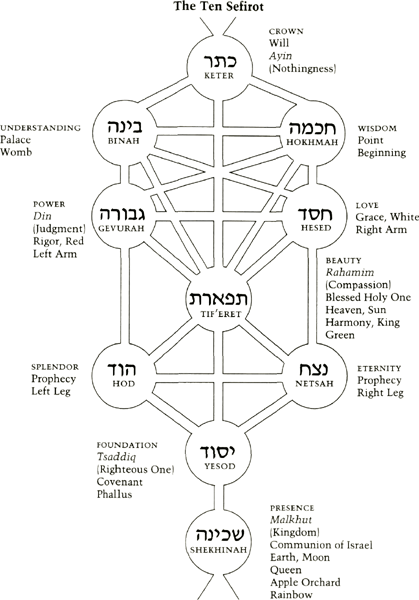

The rabbinic concept of Shekhinah, divine immanence, blossoms into the feminine half of God, balancing the patriarchal conception that dominates the Bible and the Talmud. Kabbalah retains the traditional discipline of Torah and mitsvot (commandments), but now the mitsvot have cosmic impact: The secret of fulfilling the mitsvot is the mending of all the worlds and drawing forth the emanation from above.human participation, God remains incomplete, unrealized. It is up to us to actualize the divine potential in the world. God needs us.

Kabbalah owes its success to this piquant blend of tradition and creativity, loyalty to the past and bold innovation. The kabbalists grew adept at walking the tightrope between blind fundamentalism and mystical anarchy, though a number of them lost their balance and fell into one extreme or the other. Remarkably, despite their startling ideas and sometimes shocking imagery, the kabbalists aroused relatively little opposition, compared to some of the famous Islamic Sufis and Catholic mystics such as Hallaj and Meister Eckhart. No doubt this was due in part to the esoteric method of transmitting Kabbalah. At first, the secret teachings were conveyed orally from master to disciple and restricted to small circles. Even when written down, the message was often cryptic, sometimes concluding: This is sufficient for one who is enlightened, or The enlightened one will understand, or I cannot expand on this, for thus have I been commanded.

From the beginning of the movement in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Kabbalah was promoted by renowned, learned rabbis such as Rabad of Posquires and Nahmanides. Strongly committed to traditional observance, the kabbalists could not easily be attacked as radicals. But they were profoundly radical, and they touched something deep in the human soul.

The kabbalists made the fantastic claim that their mystical teachings derived from the Garden of Eden. This suggests that Kabbalah conveys our original nature: the unbounded awareness of Adam and Eve. We have lost this nature, the most ancient tradition, as the inevitable consequence of tasting the fruit of knowledge, the price of maturity and culture. The kabbalist yearns to recover that primordial tradition, to regain cosmic consciousness, without renouncing the world.

Visions of God

Kabbalah emerges as a distinct movement within Judaism in medieval Europe, but the experience of direct contact with the divine is already evident in the earliest Jewish bookthe Bible. When Moses encounters God at the burning bush, he is overwhelmed: afraid to look at God, he hides his face. Soon God reveals the divine name, I am that I am, intimating what eventually becomes a mystical refrain: God cannot be defined (Exodus 3:6, 14). Later, at Mt. Sinai, Moses asks to see the divine presence, but God tells him, No human can see me and live. Yet the Torah concludes by saying that God knew Moses face to face (Exodus 33:20; Deuteronomy 34:10). The prophet Isaiah sees God enthroned in the Temple in Jerusalem, accompanied by fiery angels who call out to one another, Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts. The whole earth is filled with his presence (Isaiah 6:3). The most graphic account of a vision of God is undoubtedly the opening chapter of the book of Ezekiel. Standing by a river in Babylon, the prophet sees a throne whirling through heaven, accompanied by four winged creatures darting to and fro. On the throne is a figure with the appearance of a human being, surrounded by radiance like a rainbow.

Ezekiel experienced this vision near the beginning of the sixth century B.C.E. Even before his book was canonized as part of the Bible, his vision had become the archetype of Jewish mystical ascent. Until the emergence of Kabbalah, Jewish mystics used Ezekiels account as their model. Maaseh merkavah, the account of the chariotas it came to be calledwas expounded in some circles, imitated in others. An entire literature developed recounting the visionary exploits of those who followed in Ezekiels footsteps, among them some of the leading figures of rabbinic Judaism. The journey was arduous and dangerous, requiring intense, ascetic preparation and precise knowledge of secret passwords in order to be admitted to the various heavenly palaces guarded by menacing angels. The final goal was to attain a vision of the divine figure on the throne.

The danger of the mystical search is conveyed by a famous report in the Talmud of four rabbis who ventured into pardes, the divine orchard, or paradise:

Four entered pardes: Ben Azzai, Ben Zoma, Aher,

and Rabbi Akiva. Ben Azzai glimpsed and died.

Ben Zoma glimpsed and went mad. Aher cut

the plants. Rabbi Akiva emerged in peace.

Aher, the other one, is the nickname of Elisha ben Avuyah, the most famous heretic in rabbinic literature. The exact nature of his heresy is unclear; the metaphor of cutting the plants may refer to his conversion to Gnostic dualism. In any case, only Rabbi Akiva, we are told, emerged unscathed.