A Very Brief History of

Eternity

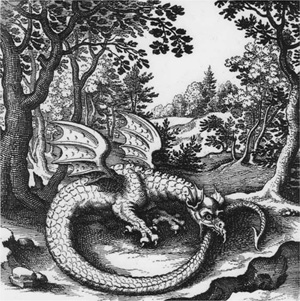

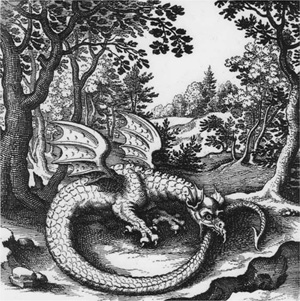

Frontispiece. Ouroboros, ancient symbol of eternity. Seventeenth-century engraving by Lucas Jennis, in an alchemical treatise.

Carlos Eire

A Very Brief History of

Eternity

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eire, Carlos M. N.

A very brief history of eternity / Carlos Eire.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13357-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. EternityHistory of doctrines. 2. Civilization, Western. I. Title.

BT913.E74 2010

236.21dc22

2009022951

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion text with

Helvetica Neue Condensed Display

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 9 10 8 6 4 2

IN MEMORIAM

Richard Charles Ulrich (19152006)

Evelyn Decker Ulrich (19132003)

Aquella eterna fonte est escondida,

qu bien s yo d tiene su manida,

aunque es de noche.

That eternal wellspring hides

though well I know where it abides,

in spite of the night.

St. John of the Cross

Contents

I

Big Bang, Big Sleep, Big Problem

II

Eternity Conceived

III

Eternity Overflowing

IV

Eternity Reformed

V

From Eternity to Five-Year Plans

VI

Not Here, Not Now, Not Ever

Appendix

Common Conceptions of Eternity

Eternity

A Basic Bibliography

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

T he idea for this book emerged unexpectedly on a crowded and noisy train, on a dimly lit December afternoon, as I was returning home from a meeting of the Virginia Seminar on Lived Theology. We were still getting acquainted with one another, the members of this group, and wrestling with how each of us might best conceive of a project that would shed light on the ethical, pragmatic dimension of religious belief. I dont think it was anything specific that anyone said during those three days that forced the idea out of its hiding place in my brain; it was just the overall effect of sustained thinking in the company of incredibly gifted and affable individuals that did the trick, I think.

Of course, any book that shows up in such a way has been gestating for years, invisible to the inner eye. All of my life, for as long as I can remember, I have puzzled over death, which has always struck me as the greatest injustice of all, and so senseless. Maybe it has something to do with all those executions I saw broadcast on live television when I was a small boy in Havana, courtesy of Fidel Castros revolutionary justice. Maybe not: perhaps I was already thinking this way before Fidel rolled into town and Che started killing people right and left simply for having the wrong ideas in their heads. But its not the source of the obsession that matters; rather, its the simple fact that my scholarly work has been informed by it for the past thirty-five years, in one way or another.

This fixation has also affected my personal life, of course, but this isnt the place to dwell on that. Lets just say that its made me feel out of sync, especially at sporting events, where everyone else seems to care so much about mere numbers on a scoreboard. The only thing I seem to understand and appreciate in sports is talk of sudden death overtime, and thats not out of any interest in the outcome of the game; its all about the metaphor.

Until that December afternoon, what I hadnt realized was that, in addition to contemplating death and extinction a bit too much, Id also been keeping a close eye on its opposite, eternity. Then, after I saw that pinpoint of light, another insight followed, overwhelming in its lucidity: I saw the big circle. I realized that my own behavior has been determined in large measure by how I think about my eternal fate, day in and day out, and that all of my thinking on eternity has been inextricable from the cultural matrix in which I have lived. And then I realized that we are all about ends, we human beings: whether they are small ends, such as some instantaneous gratification, or some larger end, such as revolution, death, retirement, or some hope of an afterlife, we structure our choices according to some end, and many of our ends are determined by our cultures. And what end could be bigger than eternity, especially in a culture that has been predominantly Christian for centuries?

I realized, as a group of very noisy Catholic schoolgirls filled the train with their voices, that the concept of eternity was an essential component of the history of Western civilization, a large piece of the puzzle that had vanished from view. Eternity had a history and history had eternity in it, at least in the West, and hardly anyone seemed to notice. It mattered little that those plaid-skirted schoolgirls and no one else on the train seemed remotely conscious of eternity at that moment. No one seemed too aware of the electric current that propelled the train, either, or of the so-called self-evident truths and unalienable rights that allowed them all to pursue happiness freely, attend a private school, and choose between the New York Post and the New York Times. The deeper that something is embedded in your daily routine, the harder it is to see it or to appreciate its historical contingency.

Eternity had a history, it dawned on me, as did those unalienable rights; and maybe it was high time for someone to write about it, concisely, for even when its absent from view, eternity can make a hell of a difference. As a historian of religion and a specialist in the early modern periodwhen the concept of eternity underwent a major redefinitionI knew that eternity had definitely played a role in the shaping of the West.

So I began to think about this history of eternity.

One thing led to another, and before too long I was discussing this project with Fred Appel, at Princeton University Press, who encouraged me to pursue it. Then I received an invitation to deliver the Spencer Trask Lectures at Princeton, in November 2007, and those three lectures became the framework for this book. I would like to thank Fred for making this book happen, for without his encouragement and his wise counsel it might have never seen the light of day or taken its present shape. I also thank those on the Public Lectures Committee at Princeton who extended the invitation and made my visit so enjoyable and productive.