Contents

FROM GREECE TO THE RENAISSANCE

CHANGE AND TASTE

REVIVAL AND RENEWAL

MODERNISM AROUND THE WORLD

NEW DIRECTIONS

architecture ideas

you really need to know

Philip Wilkinson

New York London

2010 by Philip Wilkinson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to .

ISBN 978-1-62365-178-7

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Random House Publisher Services

c/o Random House, 1745 Broadway

New York, NY 10019

www.quercus.com

Introduction

This book is about the key ideas that have underpinned Western architecture from the time of ancient Greece to today. These ideas cover a variety of fieldsfrom technology to decoration, from planning to craftsmanship, and from how to interpret the past to how to build for the future. They include the intellectual sparks that created medieval Gothic, notions that lay behind the idea of the garden city and the technological innovations that produced the skyscrapers.

The first half of the book covers the rich past of architecture from its roots in the style of the Greeks to the revolutionary developments of the late 19th century. It shows how architects and builders created not only a fund of historical stylesfrom classical to gothicbut also all kinds of ideassuch as prefabrication and the garden citythat interest architects today.

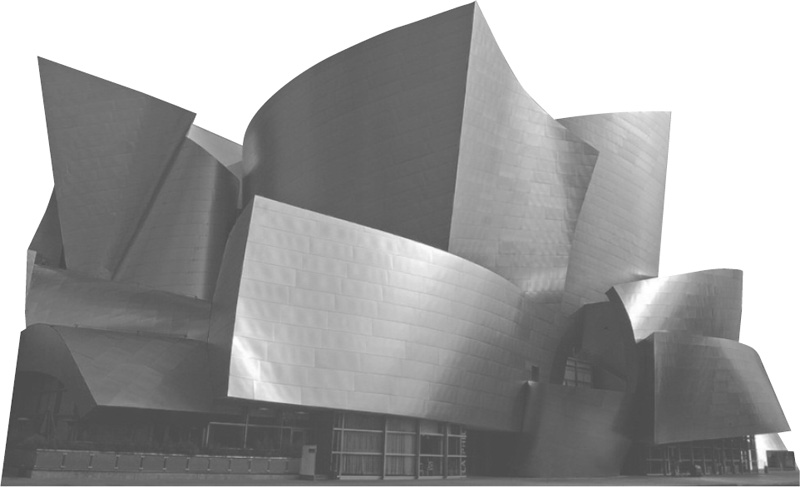

The books second half begins with the big renewal of the 20th century. The modernism of the early part of the 20th century developed through an explosion of ideas, most of which stripped architecture and design of extraneous decoration and exploited materials such as concrete, glass and steel. From the sculptural forms of the expressionists, to the pared-down, functionalist, concrete-and-glass buildings of the International Style, architects turned their backs on the past. As a result, in the 1920s and 1930s, architectural ideas had never been so rich or so novel.

But great ideas provoke reactions and reinterpretations and the last few decades have seen countless new notions about where architecture should go next. The shocking forms of Archigram and deconstructivism, the irony and allusion seen in postmodernism and the new directions of green architecture have been among the very varied results. They all point to a healthy pluralism in todays architecture. Architecture has rarely had so much variety, or so much potential.

The orders

In ancient Greece, probably around the sixth century BC, architects and stonemasons developed a system of design rules and guidelines that they could use in any building whose construction was based on the column. These guidelines later became known as the orders and they went on to have a huge influence, not only in ancient Greece and Rome, but also in later architecture all over Europe, America and beyond.

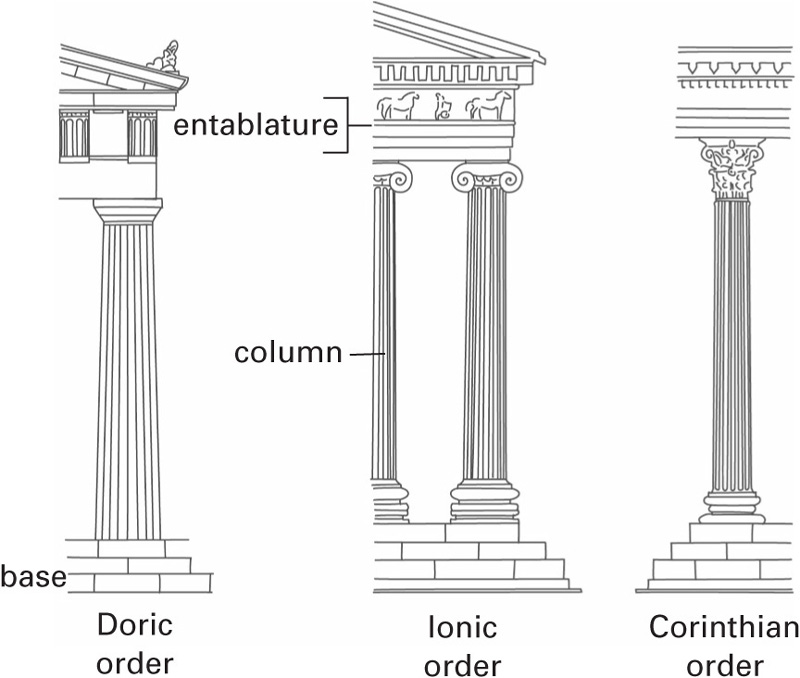

The orders are most easily recognized by their columns, especially by the capitalsthe features that crown each column. The three Greek orders are Doric, with its plain capitals, Ionic, with its capital made up of volutes or scrolls, and the Corinthian, which has capitals decorated with the foliage of the acanthus plant. The simple Doric order was invented first, and some scholars believe that its design, used with such flair by Greek stonemasons, originated in timber building. Doric temples, such as the Heraion at Olympia, go back to c. 590 BC. The Ionic appeared soon afterward, while the earliest Corinthian columns date to the fifth century BC.

To these three the Romans added two further orders, the plain Tuscan and the highly ornate Composite, which combines the scrolls of the Ionic with the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian.

The entablature and proportions There is much more to the orders than the columns and capitals, because what the column supports is also part of the order. Above the column is a lintel made up of three horizontal bands. First comes the architrave, which is usually quite plain; then the frieze, which may contain ornate sculpture; and on top of this the cornice, a molded section that makes the transition between the horizontal part of the order and the roof or gable. Together, these three horizontal bands are called the entablature.

Vitruvius and the orders

The Roman writer Vitruvius produced his handbook De architectura (On Architecture) in the first century BC. A practical treatise for architects, it deals in its ten books with many aspects of buildingfrom materials and construction to specific building types. Vitruvius has much to say about the orders, dealing with their origins, proportions, details and application in buildings such as temples. In a memorable passage he describes how the three Greek ordersDoric, Ionic and Corinthianrepresent, respectively, the beauty of a man, a woman and a maiden. Vitruviuss book, much reprinted and translated from the Renaissance onward, had a huge influence on the architects of later centuries when they revived the classical style.

Proportions were also an important aspect of the orders. The height of a column, for example, was expected to be in a certain ratio to its diameter, so it did not look too long and spindly or too short and squat. So the height of a classical Greek Doric column was usually between four and six times its diameter at the bottom (the columns tapered slightly toward the top). There were also parameters for the depth of the entablature in relation to the column diameter, and so on.

Thus in the invention of the two different kinds of columns, they borrowed manly beauty, naked and unadorned, for the one [Doric], and for the other [Ionic] the delicacy, adornment, and proportions characteristic of women The third order, called Corinthian, is an imitation of the slenderness of a maiden.

Vitruvius, On Architecture

A set of ground rules The orders, therefore, gave ancient architects a complete set of rules from which to design any building based on columns. For the Greeks this meant temples, monuments and other important public buildings. The Romans extended the use of the orders, applying them in different ways to their greater variety of building types, from basilicas to bath houses, but still using the basic design guidelines.