CONTENTS

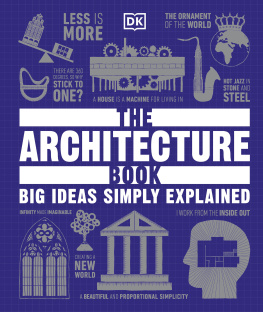

S ince the earliest days of human existence, structures have been made to provide shelter, warmth, refuge and privacy, and to facilitate worship, work and social interaction. In this respect, little has changed but in terms of development, expression, interpretation and style, everything is in constant flux. This is what makes architecture so fascinating: although our essential requirements barely alter, different times, place and cultures have produced hugely varied buildings. The factors behind this variety include religious beliefs, availability of materials, variations in climate, limits of technology and economic systems. Among the most enduring works of architecture are castles, palaces and cathedrals, many of which are physical proof of technological progress. Buildings are not just about the way they look; they are also about how they function, their practicality, construction, decoration and how they fit into the landscape.

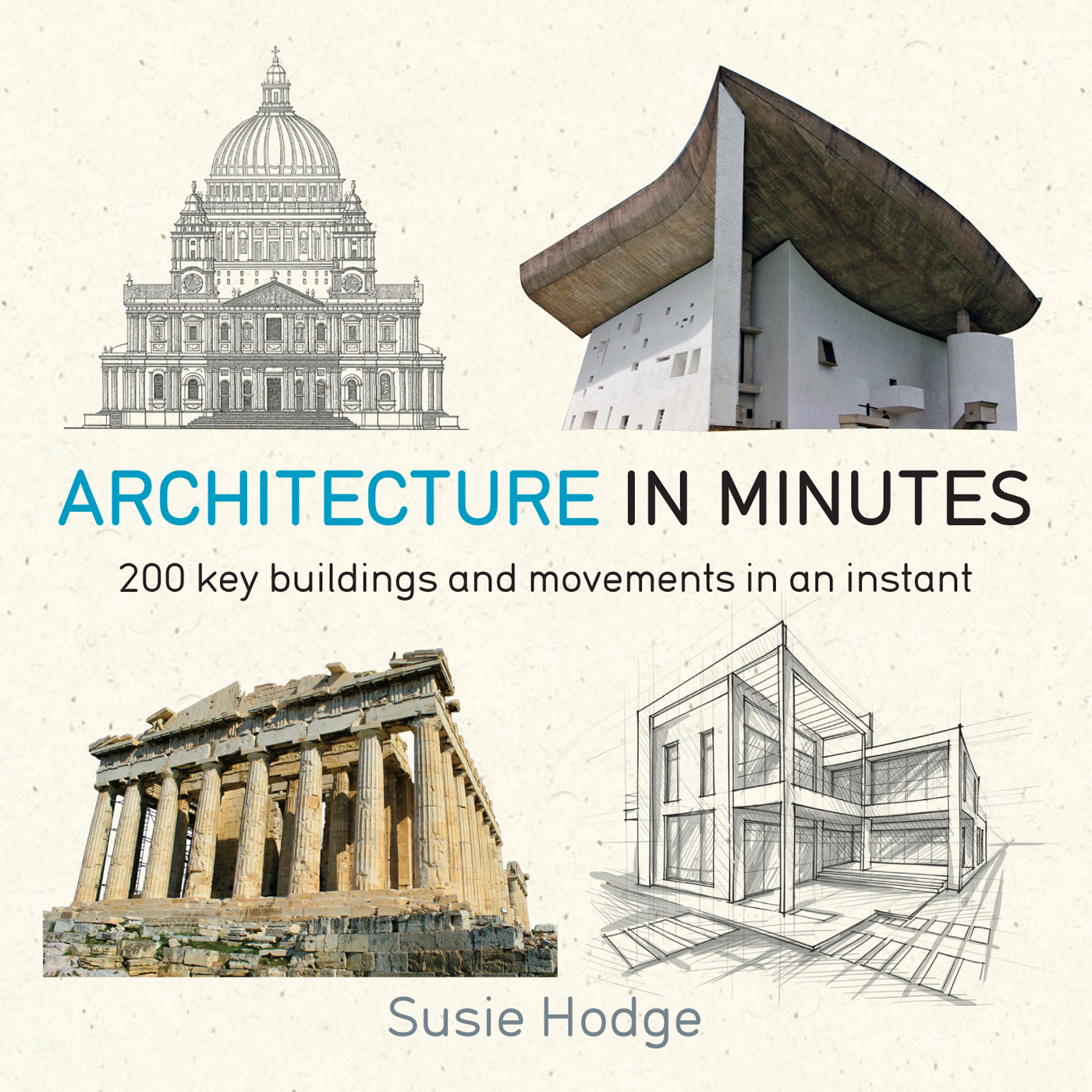

Architecture in Minutes is a brief introduction to some of the greatest architectural achievements of humankind. From the mysterious megaliths and spectacular pyramids of the ancient world, to the formidable fortresses and soaring Gothic churches of medieval Europe, and from elegant pagodas and magnificent mosques and palaces, to intricate urban developments and towering skyscrapers, this book surveys ideas, innovations and ingenuity. It considers societys changing requirements and expectations, as well as many of the architects who, through their knowledge of construction methods and materials and their understanding of proportion, aesthetics and local environments, have created unique and original buildings, instigating further change and developments over time.

In these pages, you will find iconic works of architecture, such as the Colosseum in Rome, the Parthenon in Athens and the Taj Mahal in Agra. Also explored are the architectural movements such as mannerism, neoclassicism and modernism, that put individual buildings into context, and certain exemplary architects, including Andrea Palladio, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. There are also lesser-known structures, movements and architects, providing an overview to consider, enjoy and hopefully inspire you to further investigate the fascinating world of architecture.

F rom around 5000 BCE , massive stone structures were erected across the world. Intended to be seen from great distances, the majority of megaliths (from the ancient Greek megas meaning great, and lithos meaning stone) are believed to have been used for religious rituals. Some, mainly in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Saudi Arabia, probably related to farming.

The most famous and sophisticated surviving megalithic monument is Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England (opposite), built in phases from around 3000 to 2000 BCE . Set in a precise stone circle, the giant stones are positioned with astronomical precision to align with rising and setting points of the Sun at specific times of year. The massive horizontal stone lintels and vertical posts are attached using the mortice-and-tenon technique, with carved protrusions on the uprights that fit neatly into slots on the lintels.

Mesopotamia and Persia

P redating the earliest known Egyptian buildings, the first permanent structures in the Near East were built in the area known as Mesopotamia from the tenth millennium BCE . The first culture to thrive in this region (between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in present-day Iraq) were the Sumerians, followed by the Akkadians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians and finally the Persians, who conquered the area in 539 BCE . Among these civilizations many accomplishments including agriculture, a written language and the wheel was the development of urban planning.

Architecture does not seem to have existed as an occupation, but the Mesopotamians perceived the craft of building as a divine gift taught by the gods. They were the first society to build entire cities, dominated by ziggurats tombs built to resemble the mountains where the gods lived. Cities were walled for protection, with large gateways. Mesopotamian buildings were initially made of mud bricks, but later of bricks fired in ovens.

Sumerian ruins at Naffur, Iraq

Sumerian ziggurats

Z iggurats were stepped pyramids built for the worship of gods at first by the Sumerians, but later by the Babylonians, Akkadians and Assyrians. Constructed in a stack of diminishing tiers on rectangular, oval or square bases, they had distinctive flat tops, and formed the focal point of Mesopotamian cities.

The oldest surviving ziggurat, in the ancient city of Uruk, pre-dates the Egyptian pyramids by several centuries. A shrine at the summit of the stepped platform was approached by outer stairs. The temple is believed to have been dedicated to the sky god Anu, and its corners point towards the cardinal points of the compass. Nearly a millennium later, during the Neo-Sumerian Empire, the ziggurat at Ur (opposite) was built c. 21132096 BCE . The best preserved of the ancient ziggurats, it is built with a core of mud bricks and an outer casing of fired brick. Three converging ramps lead up to a platform, from which a central stairway continues to the top, where a temple once stood.

Egyptian pyramids

T he pyramids were built as tombs for the rulers of Egypts Old and Middle Kingdoms between c. 2600 and 1800 BCE . Three types were built: step, bent and straight-sided. The most imposing are those at Giza (opposite), the largest of which was built for the pharaoh Khufu.

The pyramid shape is believed to have been favoured for the great heights that could be achieved, the notion of pointing directly up to the gods, and the commanding presence they created across the surrounding flat valleys. In a practical sense, fewer stones were required to be hauled to the top. These massive constructions some rise up to 146 metres (450ft) while some of the blocks of limestone weigh 15 tonnes were built with the utmost precision; the casing stones are so finely joined that a knifes edge cannot fit between them. Within, narrow passages lead to the royal burial chambers. Gypsum mortar held the blocks together, and the entire structures were encased in smooth white limestone quarried from the east bank of the River Nile, with the summit often topped in gold.

Ancient Egyptian temples

B uilt for the worship of gods, ancient Egyptian temples evolved from small shrines to large complexes. By the time of the New Kingdom ( c. 15501070 BCE ), temples had become massive stone structures consisting of enclosed halls, open courts and entrance pylons. Certain parts could only be entered by priests, but the public visited other areas to pray, give offerings and seek guidance from the gods.